EPISODE 1

Episode 1: The Georgia Minstrels (1865-1878)

An exploration of one of the first successful Black minstrel troupes and of the careers it launched, particularly that of its legendary leader, Charles B. Hicks.

Hosted by: Brittany Bradford

Guests include: Rhiannon Giddens

Featuring the voices of: Lynnette Freeman, Anthony Fusco, Toussaint JeanLouis, Lee Aaron Rosen

Produced by: CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience

Conceived and Written by: CLASSIX (Brittany Bradford, A.J. Muhammad, Dominique Rider, Arminda Thomas, Awoye Timpo)

Sound Design and Editing: Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube

Associate Sound Engineer: German Martinez

Theme Song: Alphonso Horne

Original Music: Jeffery Miller

Banjo Performance (Shoofly): Guy Davis

Banjo Performance (Additional): Arminda Thomas

+ TRANSCRIPT

Voice 1: When I think about Black minstrelsy I think about performances that are crafted specifically for white audiences and that are harmful to Black people, Black bodies and Black communities… Voice 2: When I think of Black minstrelsy I live in a space of conflict, because on one hand there’s a hatred of the stereotypes that were portrayed by white and Black people, and on the other hand I really do find a beauty in the reclaiming or the reclamation of minstrelsy in contemporary Black art… Voice 3: I think of Bert Williams… Voice 4: An art form that started off with white Southern men who ridiculed, denigrate… Voice 5: Robert Downey, Jr., in “Tropic Thunder” black people putting on a type of blackness (Fedna) Voice 6: When I think of minstrelsy I think of Black people having to play characters that are not human… Voice 7: If you gotta make a whole genre to tear us down… Voice 8: That is creating work for white consumption, specifically… Voice 1: Double consciousness Voice 6: Cooning and shuffling Voice 9: Exaggerated lips (Monifa) Voice 10: I think about mammies and watermelon (Sarin) Voice 9: Mocking the black body (Monifa) Voice 11: Survival and really understanding that even if I can look back at those images or video and have a sort of Lou feeling about about them that to exist in that white industry that white world is to take on those those white stereotypes that white gays and attempt to bring some sort of humanity to it if that's even possible and to be honest it makes me think of of issues that we're still grappling with today in our industry (Imani)

BRITTANY: Growing up doing theatre, particularly once being a part of the black theatre community, I had never really learned about minstrelsy at all. It was always treated as a taboo subject. A way that white performers had co-opted and bastardized the black experience. Something to be ashamed of. Something that we may see perpetuated now in images like Aunt Jemima, or Uncle Ben’s Rice…

I had never thought about it in terms of its cultural significance to the black community. I had never thought about the complexities and nuances of those black artists seeking to perform something, anything, during that time. I never thought about it as something to be celebrated. I hadn’t considered the ways in which, by connecting minstrelsy purely to the white experience, that I, that perhaps we, completely negate and devalue the work of black artists that were operating in this form at the same time.

I started to ask myself questions about minstrelsy, as I connected it to being a black artist today. Who were those people that were making art during this time period? And not just in a basic 2-dimensional, historically factual sense of what the names were, but what were their lives like? How did they love? Who did they love? What art did they value? How did they get into this form? Were they agitators and activists in their own right? Is it even possible to find the nuances of their character, their being now, or has that been lost to the history books, or rather lack of history on them?

We see this “selective exclusion” time and time again, and it is not unique to simply minstrelsy.

Throughout the history of the American theatre, Black artists have always been at the forefront of innovation. From the advent of musical comedy and the explosion of experimental theatre, to the elegance of opera and bawdiness of vaudeville, Black artists have consistently created work that builds community as a means of resistance and to tell an array of stories. While the history books have included some of these extraordinary achievements, most of the stories have been left untold.

As creators, producers and technicians, the rich history of Black theatre lives on in us as contemporary artists in dynamic ways. As we examine more and more why and how we do what we do, we look back to artists, activists, innovators, and trailblazers who have defined the theater past in order to inform our theatre future.

CLASSIX is a collective committed to exploring theater and performance through an exploration of works by Black writers. My name is Brittany Bradford, and I am one of the members of this cohort.

This podcast, (re)clamation, is our attempt to stage an intervention in the current conversation around theatre history. (re)clamation recenters and uplifts the Black writers and storytellers of the American theatre - both the celebrated and the forgotten. Each act of the podcast will explore a different era or theme in Black theater history through interviews, conversations, and excerpts of first-hand accounts.

I’m going to be your host for this era. Black Minstrelsy & Black Performance in the era of Minstrelsy. I have a lot of questions, and I’m sure you do too.

The big one for me: how do you decentralize the exploration of minstrelsy from the perspective of the white performer to centralizing the experience and history of the black performer?

Is it possible to not have to cancel an entire subset of black art, but perhaps maybe, to learn how to examine it, maybe appreciate it, but also hold it accountable to difficult questions? This is my journey, and perhaps it is your journey too.

Over the course of the next six episodes we’ll be joined by some of the CLASSIX team and some special guests. And after that time, we can come back together and see if our viewpoints on minstrelsy have changed at all. Or what has been enhanced. What has been solidified. And where we were proven wrong.

Produced by Theatre for a New Audience and the folks at Classix, welcome to Episode 1 of (re)clamation.

Now, as soon as we hear the word “minstrelsy” it brings up a lot of feelings. We asked some of our friends, “What comes to mind when you think of Black Minstrelsy,” and you heard some of their responses earlier. Here’s another by musician Rhiannon Ghiddens, when we interviewed her about the subject:

RHIANNON GIDDENS “You know, you have from the 1820s, and 30s, let’s say, 1830s, to like, Bugs Bunny, you have a massive, you know, amounts of change. Even before Emancipation and after Emancipation, minstrelsy is totally different, you know, because the purpose that it is, you know, serving has changed. Right now it's so elementary, you know, people don't even - it’s just like “blackface, ah, bad”. Which is why I've been approaching it from a musicological point of view, because previously, it's not to say that there weren't black musicians talking about minstrelsy, I just wanted to add my voice to it, because I just feel like we have a unique position within talking about minstrelsy and I think it's a really important voice to have. We just need to be more in the conversation because I think we can engage with the complexities of it in a different way. There's so many academics and so many amazing researchers who've been writing these books that I've sort of been, depending on. I've been really focusing on the banjo element of it because, again, that is something that's misunderstood. So I've just been focusing on that, because it has been a huge I mean, you know, it was such a huge part of minstrelsy and it stands for so much that we get wrong about the American cultural narrative.”

BRITTANY So, why minstrelsy?

James Weldon Johnson once said, “The real beginnings of the Negro in the American theatre were made on the minstrel stage.” Minstrelsy informed dance, drama, performance and everything that came after it. Minstrel shows were so popular that they became, for all intents and purposes, THE national art form.

Now Johnson is really talking about two distinct things here: 1st, he’s referring to what we’ll call Blackface Minstrelsy – This is white cultural appropriation and imitation - a bastardization of Black culture where white performers created Black characters and stereotypes that continue to resonate long after the original minstrel show has disappeared. In other words, this is what we tend to talk about when we talk about minstrelsy. The other thing Johnson is referring to, and what we’ll be exploring in this podcast, is what we’ll call Black Minstrelsy, the appearance of African Americans on stage in black minstrel troupes in the 1860s and beyond. These troupes were not the first iteration of black theatre excellence – that honor belongs to William Brown’s African Grove Theatre and to its breakout stars, James Hewlett and especially, Ira Aldridge, whose reputation lingers even to this day. Still, Johnson argues, the work of Brown and Aldridge, though not forgotten, left no descendants. The black minstrel troupes of the late 19th century, on the other hand, provided training and stage experience that would seed the next generation of performers, composers, writers, and producers.

So, let’s take a step back. What actually is a minstrel show?

A minstrel show was an evening of entertainment, approximately one-hour and forty-five. The first minstrel show took place in 1843, and set off an immediate craze, but it wasn’t until 1846 when a group called the [Christy Minstrels] established the conventions of what we now think of as a minstrel show.

There was a semicircle of performers onstage with a character called the Interlocutor in the center. The Interlocutor was the host. Picture an elegantly attired, eloquent and somewhat pompous straight man in a comedy pairing, right? On either side of the Interlocutor were the End Men. Known as Tambo and Bones, named for their instruments, they were the jokesters, and dressed as quote-unquote “plantation darkeys.” These were the central characters for years to come.

Another defining element of a minstrel show was its three-part structure:

Part 1: The troupe marched onto stage and paraded around the chairs until Mr. Interlocutor announced, “Gentlemen, be seated!” What followed would be “a jig, later called a breakdown, followed by a sentimental ballad. This was all interspersed with rapid repartee, riddles, and jokes between the end-men and interlocutor, and each member might perform his specialty, like a jazz band might give a chorus to its musicians.

Part 2: The olio, or variety section. This was a section of song and dance, acrobatics, performers making music with glasses and pipes; The featured segment here was called “the stump speech”, which was a comic discourse (often on a current topic), full of malaprops, that was usually performed by one of the end men dressed as a doctor, lawyer, or a woman, because in the early days there were no women in the minstrel shows...we’ll get to more of that later.

Part 3 was the finale - it was a sketch or short one-act play. Before the mid-1850s, these finales were usually plantation skits, featuring individual songs and dances and ending in a rousing group number. The plantation skits were...exactly what they sound like – short pieces that showed clips of what life was like on a plantation. That led to short parodies usually of an opera or Shakespearean tragedy. Historian and author Robert C. Toll wrote, "All of these non plantation skits were basically slapstick comedies, nearly always ending in a flurry of inflated bladders, bombardments of cream pies, or fireworks explosions that literally closed the show with a bang."

While the minstrel show was almost exclusively white in the beginning, there were some notable exceptions. William “Juba” Lane (named the “father of tap dance”), gained international fame on the minstrel stage, and black troupes popped up here and there as early as 1849. But in the first twenty years of the minstrel show, no Black troupe managed to embed itself into the national psyche. That all changed in 1865.

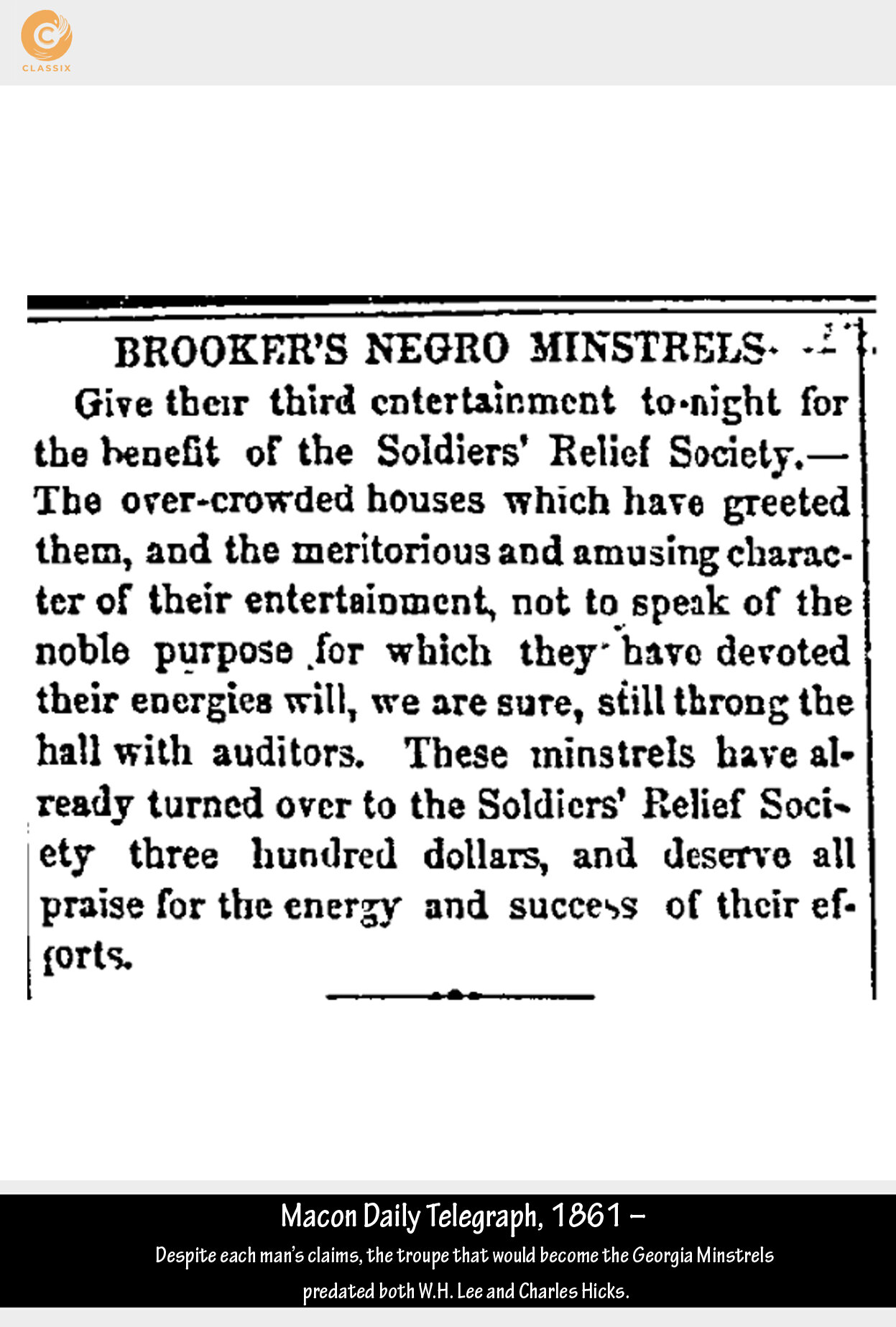

During the Civil War, a group of 16 newly emancipated musicians in Macon, GA, got together and created a troupe (which in and of itself is just amazing, right?) And On July 4, 1865 - nearly two months after the War ended - they gave their first official performance at an Independence Day celebration for union troops. This was the debut of what would become one of the most renowned troupes of this period: [The Georgia Minstrels.]

There were two white managers and agents also attached to the troupe- WH Lee, who was a Union soldier, and George W. Simpson, a newspaper man. We don’t know if Lee and Simpson were involved in the formation of the group or if they came on board as promoters, but they were there. Now minstrel troupes tended to be named either for their place of origin, or for the lead performers in their group, and in this first iteration the group took its name from both the state of Georgia and one of the troupes members, John Brooker.

Brooker’s Georgia Minstrels may have started in Macon, GA but they were not planning to stay. In this early era of Emancipation, Black America’s place within the United States was shifting day to day and although the road ahead was unknown, there was a sense of possibility for a new way to live. Brooker and his compatriots made a decision to get out on the road and see where it would take them.

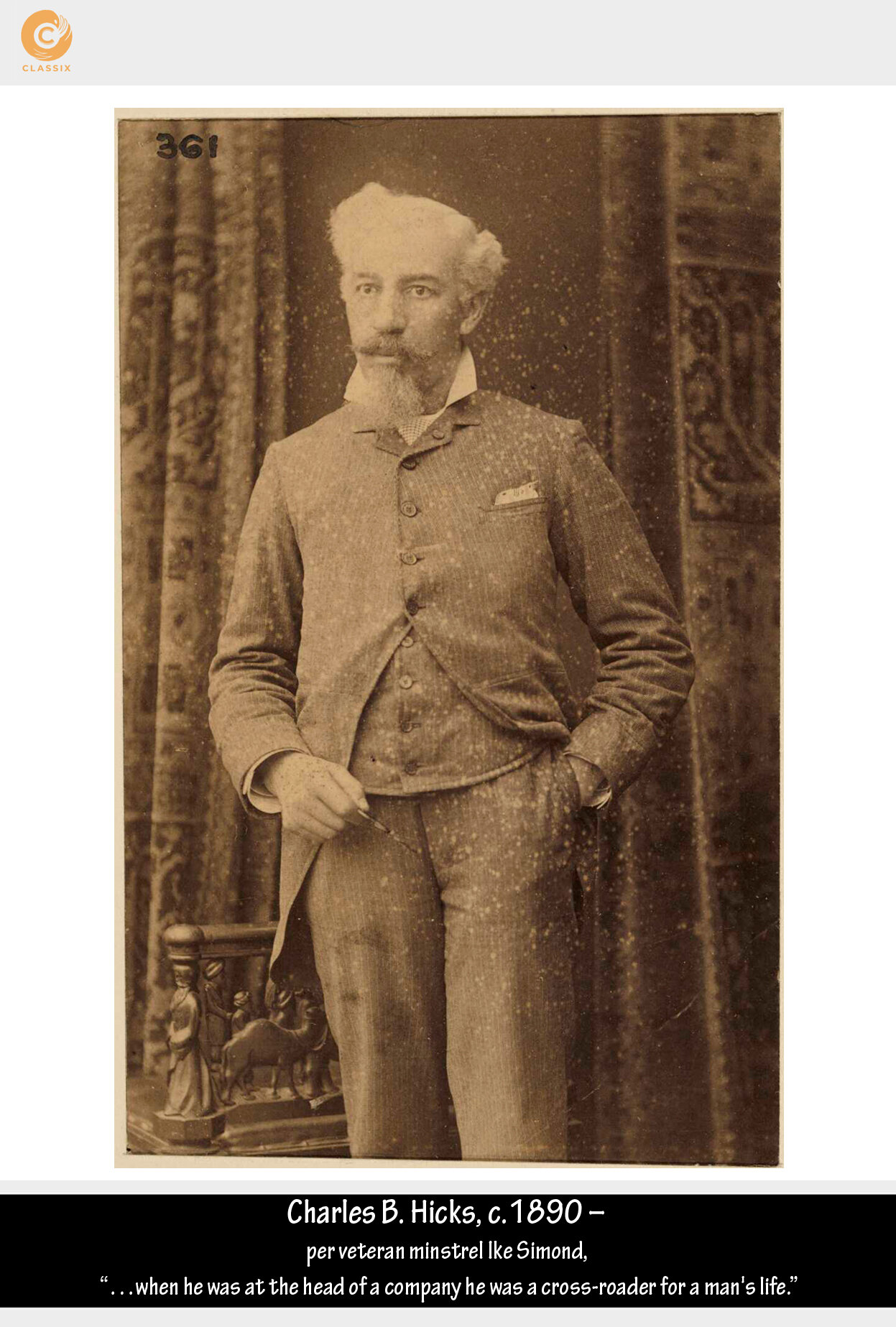

Within two months they would arrive in Indianapolis, Indiana. This is where they met the man who would become one of the savviest businessmen of the time, Charles Hicks.

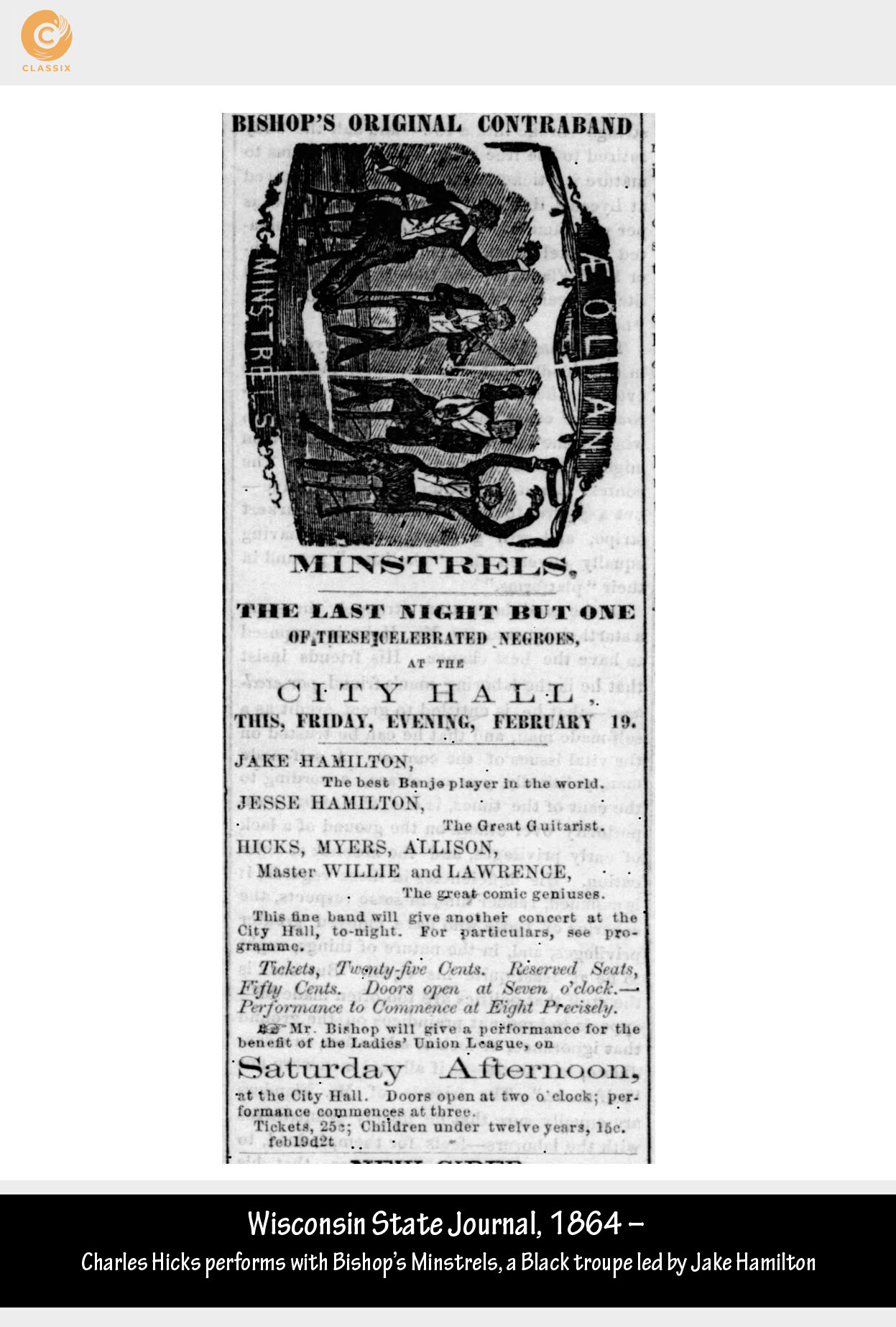

Hicks’ exact early history is quite murky and unknown. He was born in Baltimore around 1840. The earliest we can place him is with a group called Bishop’s Minstrels (later Hamilton’s Contraband Minstrels), a Black troupe touring the midwest in 1864, led by banjo player Jake Hamilton. In March of 1865, there’s an ad in the New York Clipper where Hicks advertises his services. The fact that we first hear about Hicks through the lens of advertisement, by the way, seems quite serendipitous, as he would later become extremely skilled at garnering press for himself and his troupes.Now this 1865 ad says, “Minstrel and Equestrian Managers - Hicks is open for engagements, business, song, dance, bones and tambourines”. One thing is for sure - Charles Hicks was a man of many talents. He was a performer, a promoter and an entrepreneur, but most importantly he was ambitious, driven, and inventive.

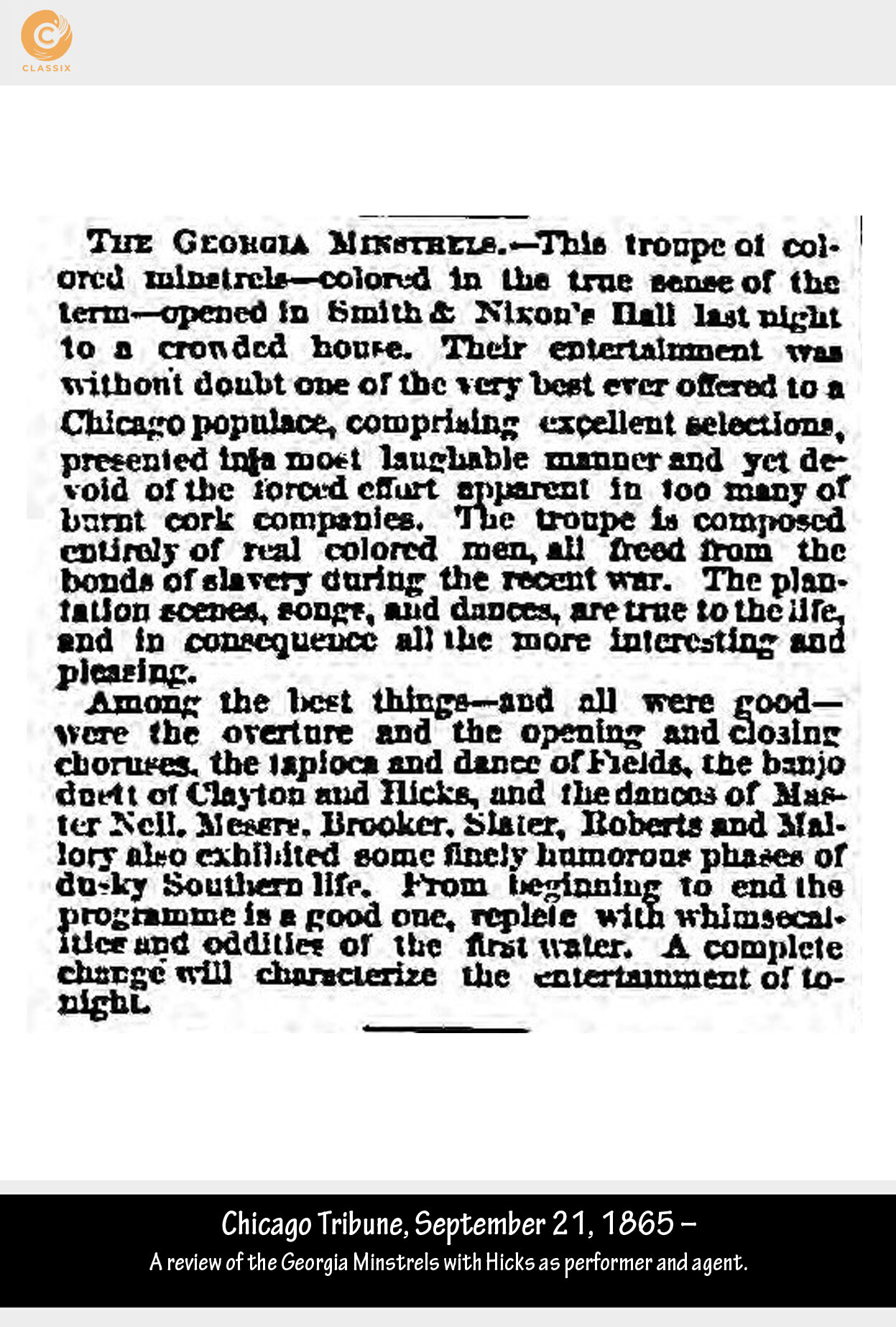

Hicks joined Brooker’s Georgia Minstrels in 1865 as a performer, quickly assumed the role of troupe manager, as well as co-proprietor (a role he shared with other troupe members). He brought in additional, more seasoned performers and shifted the focus from standard minstrel fare into a portrayal of Black authenticity. If the earliest review available to us, from the Chicago Tribune, is any indication, that was a successful strategy:

CHICAGO TRIBUNE VOICEOVER “This troupe of colored minstrels opened in Smith & Nixon’s Hall last night to a crowded house. Their entertainment was without doubt one of the very best ever offered to a Chicago populace...devoid of the forced effect apparent in too many of burnt cork companies. The troupe is composed entirely of real colored men, all freed from the bonds of slavery during the recent war. The plantation scenes, songs, and dances are true to the life….

Among the best things--and all were good--were the overture and the opening and closing choruses...From beginning to end the programme is a good one, replete with whimsicalities and oddities of the first water.”

BRITTANY With Hicks as Manager, Simpson as advertising agent and Lee as business agent the troupe headed north, continuing to promote themselves as “the only true version of Darkey Life as it really is on the Southern Plantations... NOT WHITE MEN BLACKED, But Genuine Negroes.” And to prove that assertion, the Georgia Minstrels broke from their white rivals - and from some earlier black troupes - by performing without the mask of blackface.

Let’s pause a second. That, to me, is fascinating. No one darkened their faces. There was no cork at all. This was something I wasn’t aware of. These images that we think of today when thinking of blackface, that I assumed everyone trafficked in back then, was not happening with this troupe, at least not in 1865.

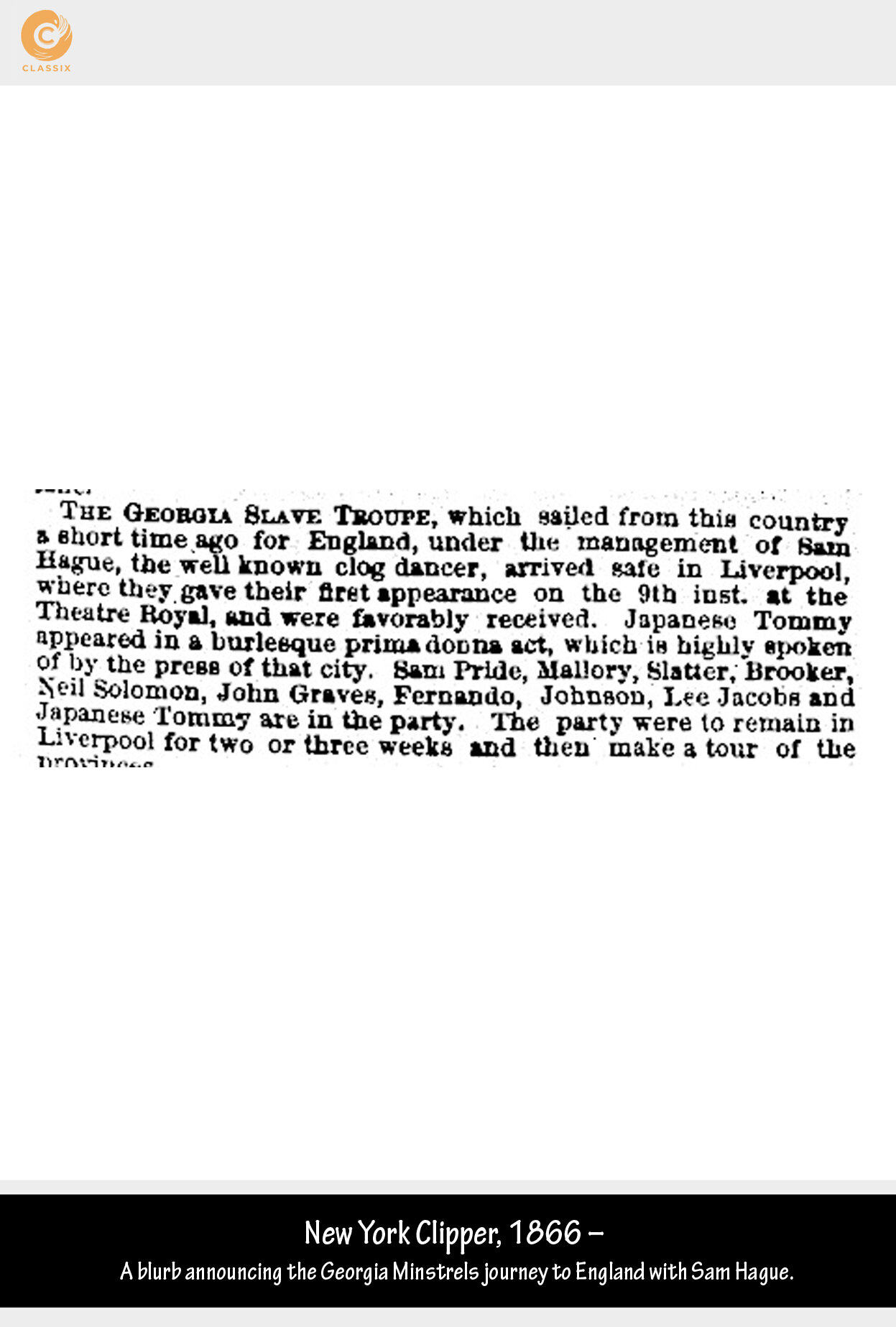

While traveling and performing in upstate New York, the troupe met Sam Hague, a white British minstrel who had been performing in the states for quite some time. This would prove to be another major turning point in the life of the Georgia Minstrels.

Hague was fascinated by the troupe and wanted to become a financial backer to take them to Europe, and sell this unique form of minstrelsy to the masses there as well. And so it was that we see a fork in the road for the Georgia Minstrels. While some, including Charles Hicks, stayed behind, at least half of the original Macon, Georgia 16 - including John Brooker - chose to go to Europe with Hague. And Within a year, the entire Original group would be in England.

On May 26, 1866, a Buffalo newspaper ran the announcement that Sam Hague had secured the Georgia Minstrels for a tour of Europe. Along with the news, the paper offered Hague a little free advice:

BUFFALO NEWSPAPER VOICEOVER “A number of [the Georgians] are a little too light in color and refined in manners and carriage to give Europeans a correct idea of a plantation slave….We would advise Sam, before he sails, to engage a few more of the Simon pure stock, of ebony color and ivory teeth, whose every look and gesture, and twinkle of the eye provokes a laugh.”

BRITTANY Anyway.

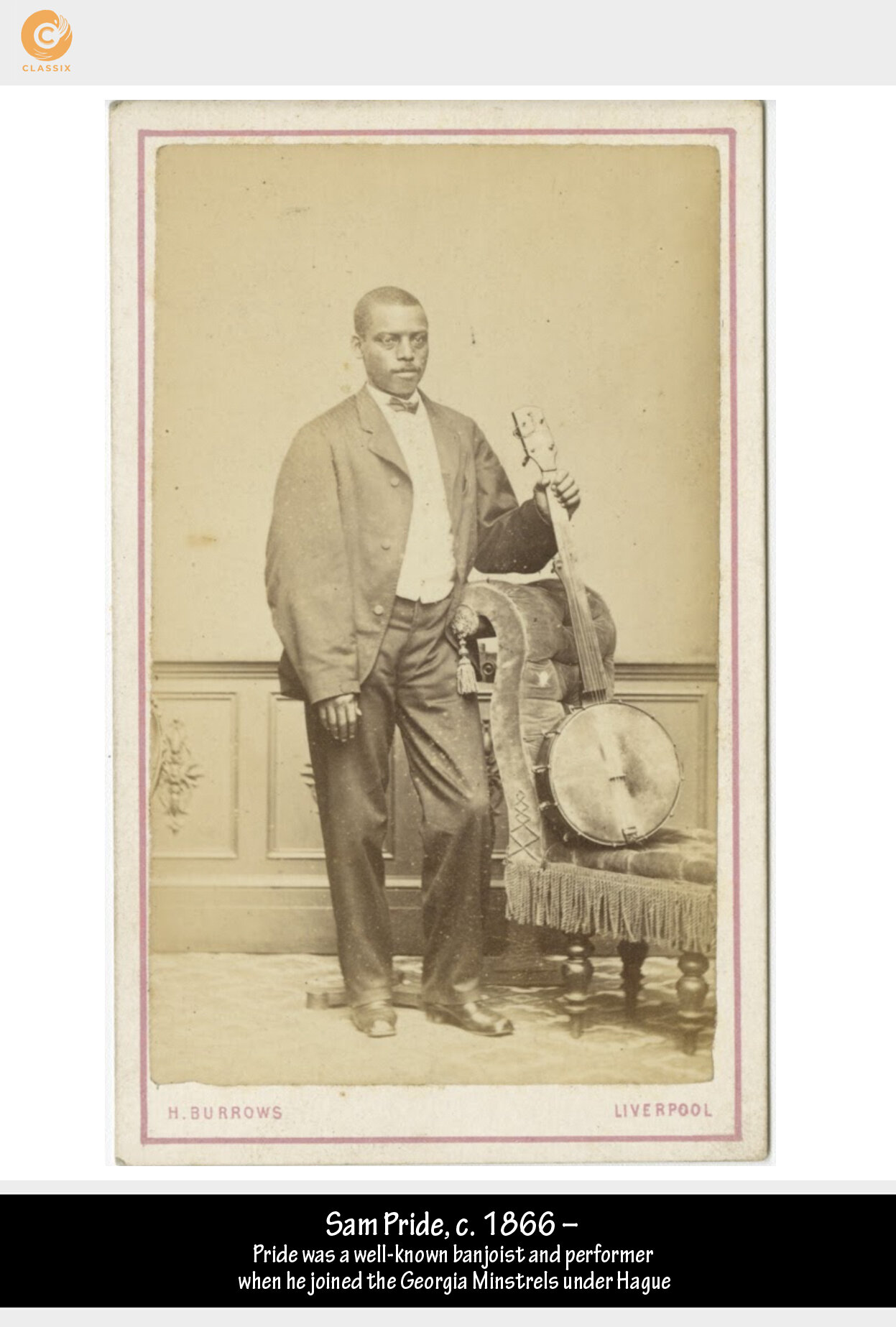

The group set sail in June of 1866. W. H. Lee went with them, along with two already-famous performers: banjoist Sam Pride, who had recently joined the Georgians, and Japanese Tommy, a little person who had first gained fame performing with white minstrel troupes.

It’s interesting to think about what such an opportunity would have meant for these men. An endeavor, led by a white man that they did not know, going to a world they were unfamiliar with. It was a journey that would be, in no hyperbolic way, life-changing. From slavery to performing in Europe in just over a year.

But there were trade-offs, as well: For the first time, the group is completely controlled by white men. Instead of “Brooker’s Georgia Minstrels, they become “The American Slave Serenaders” - sometimes referred to as “Sam Hague’s Slave Troupe of Georgia Minstrels.”. And while Hague declined to follow the Buffalo paper’s suggestion to replace the lighter-skinned troupe members, he did find a workaround. He blackened them up.

Imagine coming from a country with its own host of stains and shames, to travel somewhere that optimistically may seem to you to present more opportunities for openness in terms of self-expression and ownership, only to be asked to literally put on a mask, as if your very blackness is not what you make of it, not what your lived experience has told you it to be, but what others decide they want it to be, need it to be, in order to “see” you.

Meanwhile, in the states, Charles Hicks immediately got busy rebuilding. While it must have taken a lot of bravery to travel such a long way from home, I think it must have required a different type of bravery and trust, in oneself, to stay behind, and believe that the train you’re currently on, is the one that will take you to your proper destination.

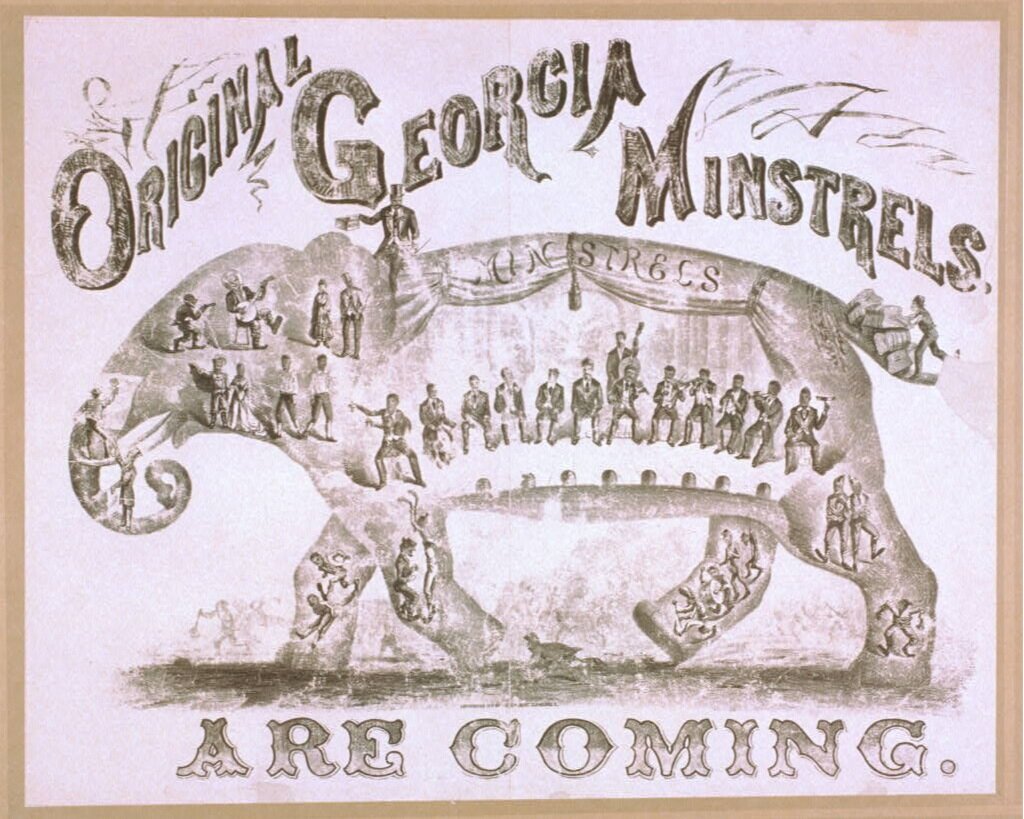

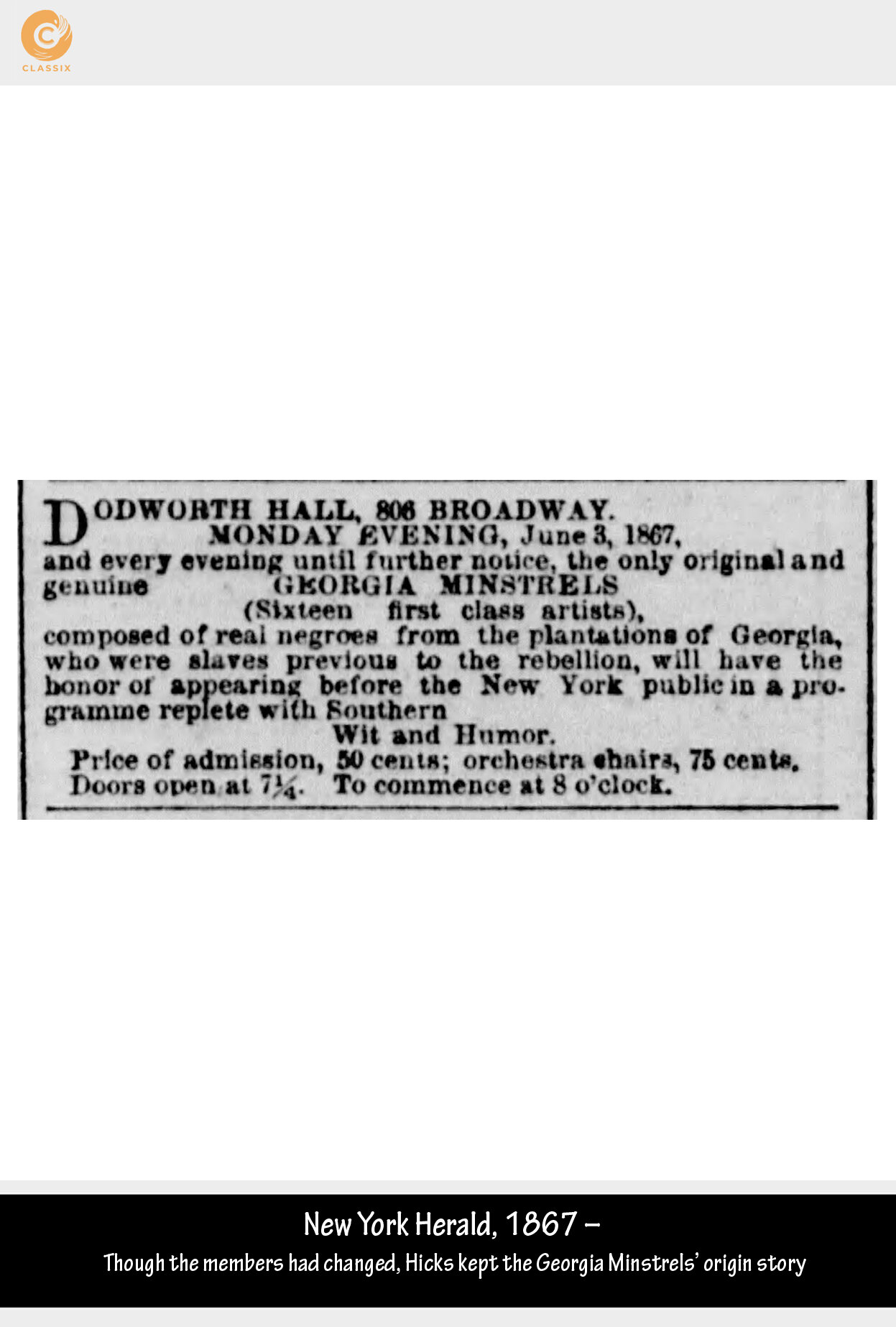

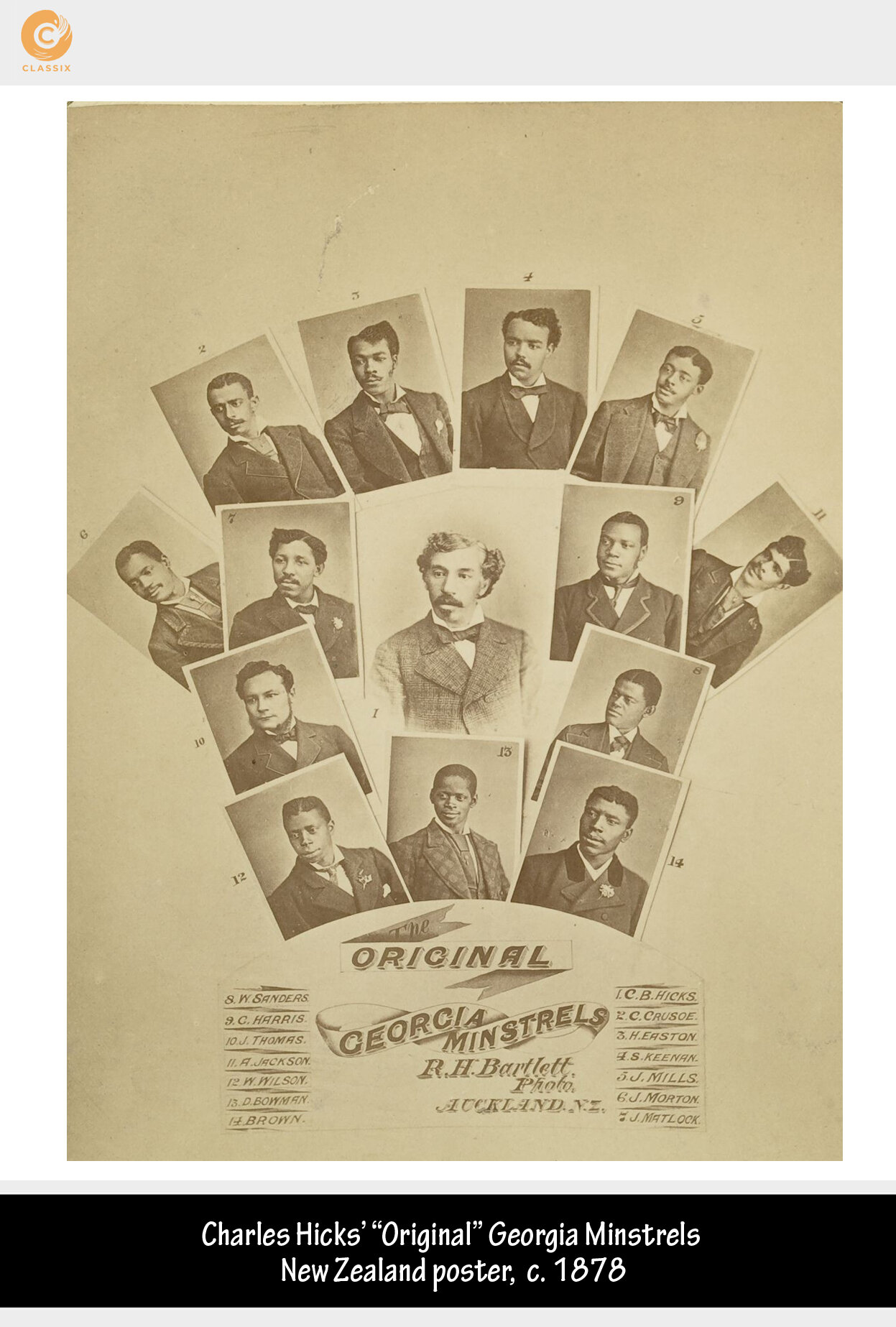

By August, Hicks was on the road with a new troupe. And what did he call this new troupe? The Original Georgia Minstrels.

Thank you so much for staying with us as we delve into Black minstrelsy. If you want to hear other programs that delve into the arts check out Backstage Stories hosted by Marcia Pendleton on WBAI. Backstage Stories features in-depth conversations with extraordinary guests about what happens behind-the-scenes in the arts, culture, and entertainment. Again, my name is Brittany Bradford, and let’s get back into it.

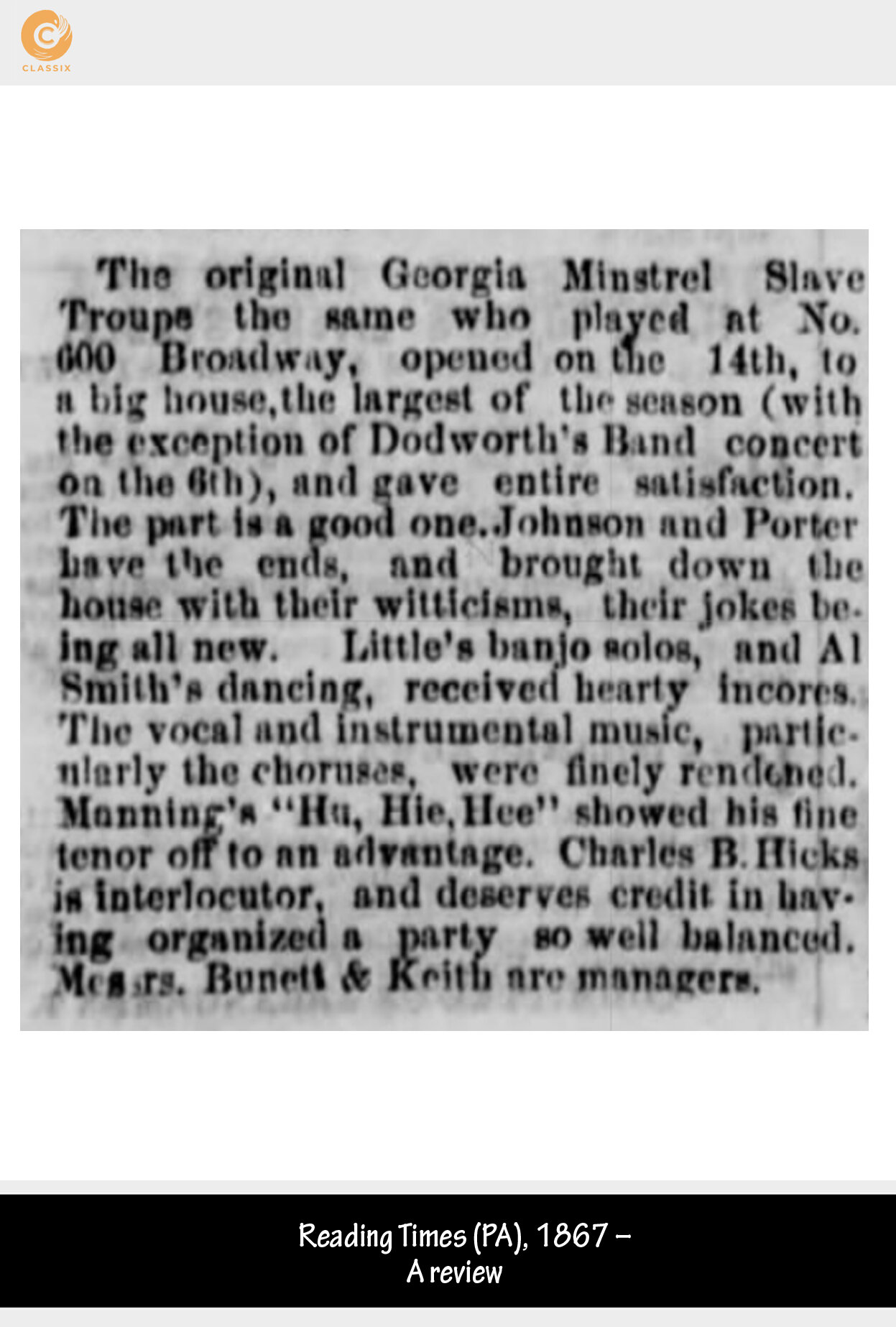

Within a few years Hicks continued to solidify the reputation of the troupe, bringing in well-experienced performers who had become well-known in other troupes. If, you know, this wasn’t a podcast about art, one might make a sports analogy here equating Hicks’ recruitment with the Georgia Minstrels, to LeBron helping assemble the current Lakers bench. But, back to art and history:

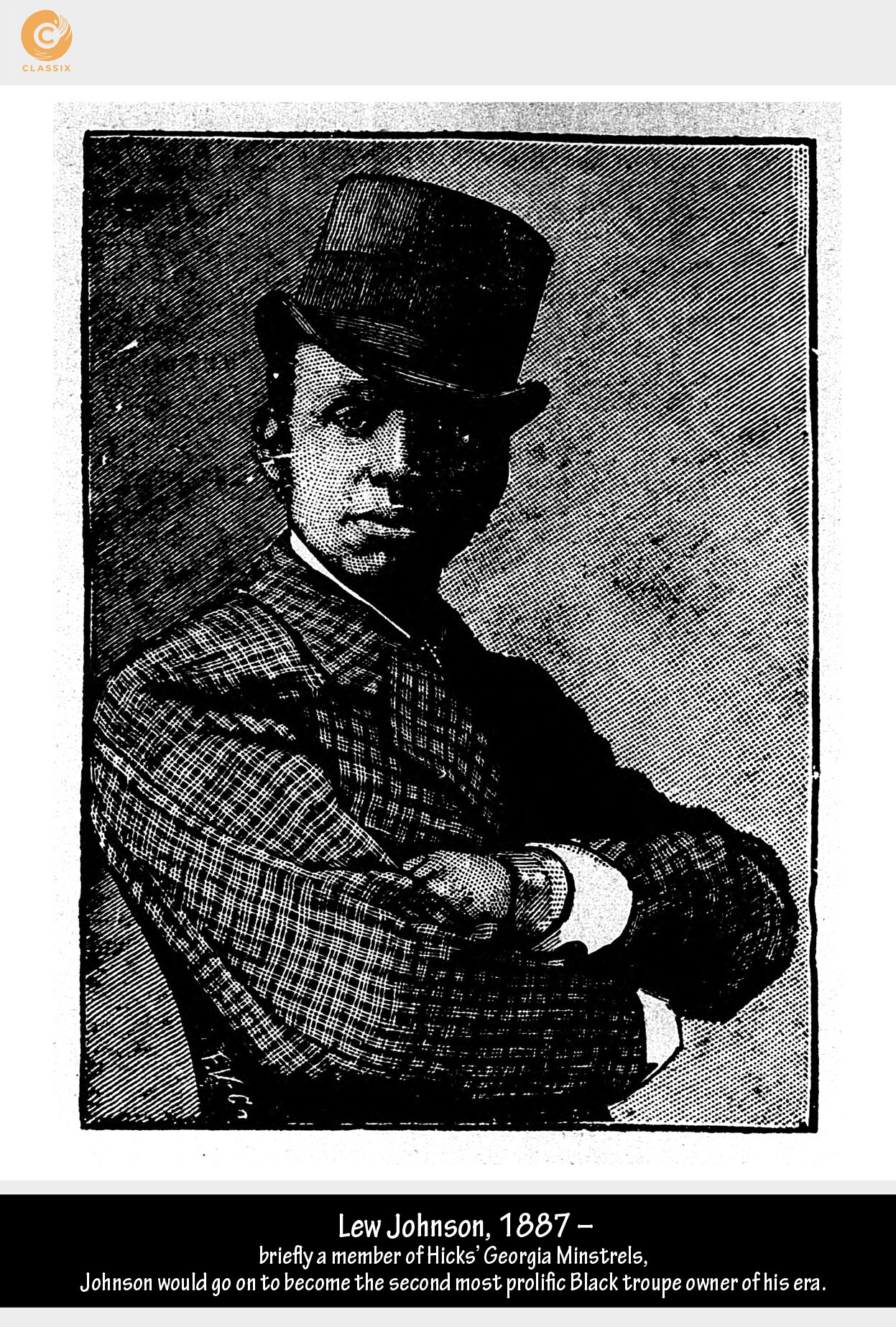

Hicks brought along his old troupe leader Jake Hamilton, once called the “best banjo player in the world”, who was former castmates with Hicks in the Bishop’s Minstrels. ; he also brings alongBob Height - an incredibly gifted end man who became Hicks’ partner, and went on to have a successful career in England; And last but not least Lew Johnson, who would go on to become the second most prolific Black troupe owner in this time period.

Hicks started to put his strategy into play. He focused on booking gigs in prominent places in and around New York City, which was at that time, the heartbeat of the entertainment scene. There was a touring scene and there was New York. And if you were going to get publicity as a minstrel troupe, the New York Clipper was how you were going to do it.

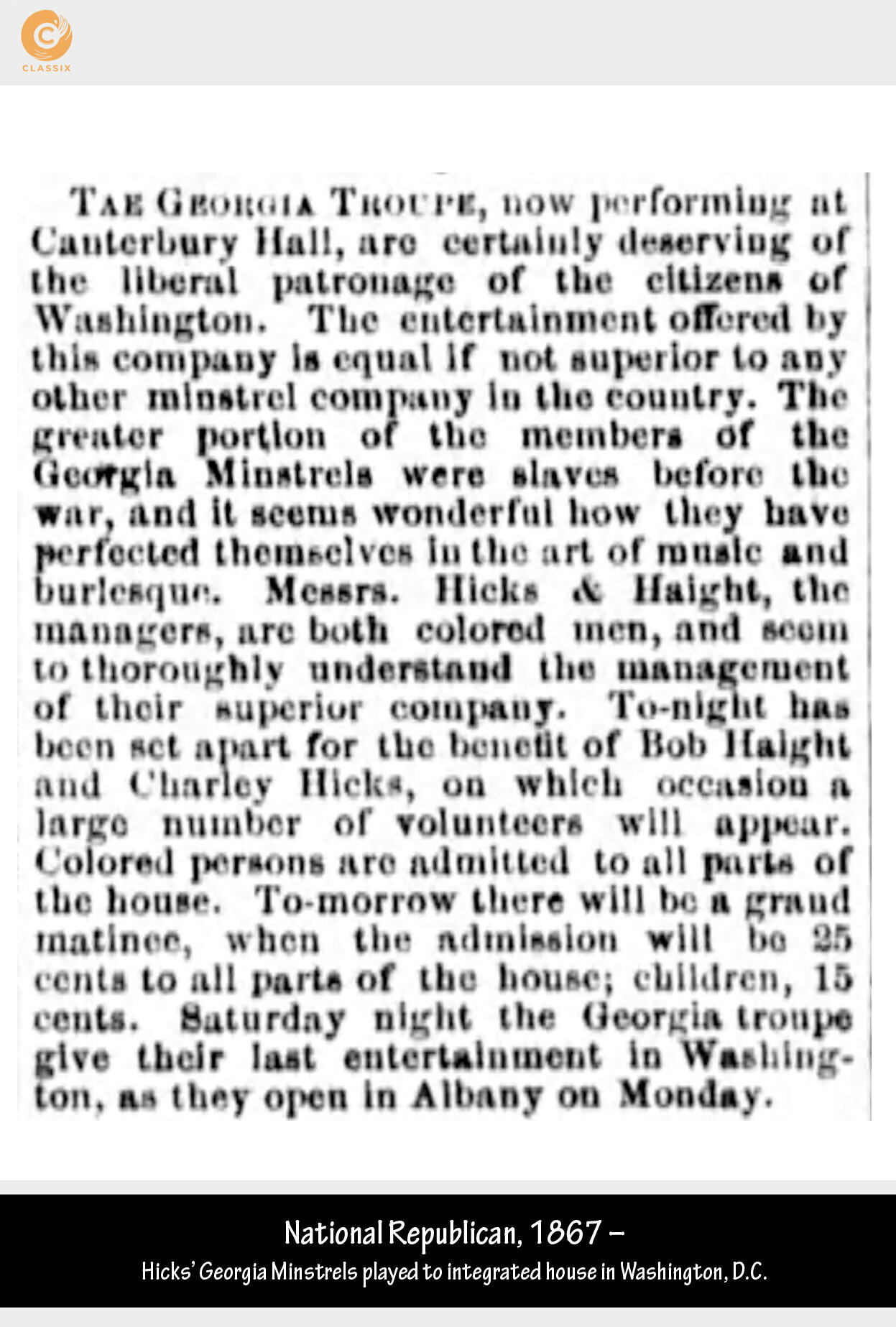

Hicks and Height also found success in cities with sizable Black audiences - cities like Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. In D.C., the troupe’s ads specifically courted this audience. “Colored persons will be allowed in all parts of the hall,” they promised. It worked. Per the National Republican, “The company...established a firm reputation here, particularly among the colored people, as the entertainments were liberally patronized by this class, though white people attended in large numbers.”

As successful as the troupe was -traveling around the world- 1868 found them touring both Panama and Canada!- Hicks was also totally living on the edge. Running a troupe was not an easy thing to do as a Black promoter.

One of the challenges was booking venues. If you don’t sell a big enough house, you don’t have enough to pay the venue. Or the lodging. Or payroll. And a particular challenge of the Black troupes was that the advance person would book the group and arrange for lodging and then the troupe would arrive only to have the hotel deny service.

Another challenge was that the safest way to get from one place to another was by private rail car. But in the early years the troupe wasn’t big enough to travel that way so they traveled by regular railroad. In the aftermath of the Civil War, as you can imagine, it was a particularly volatile time. The ability to travel safely and to have a place when you land becomes a major concern. Years later, composer and musician W.C. Handy would tell a story about narrowly escaping getting lynched on a train by finding a secret compartment in the railway he could hide in.

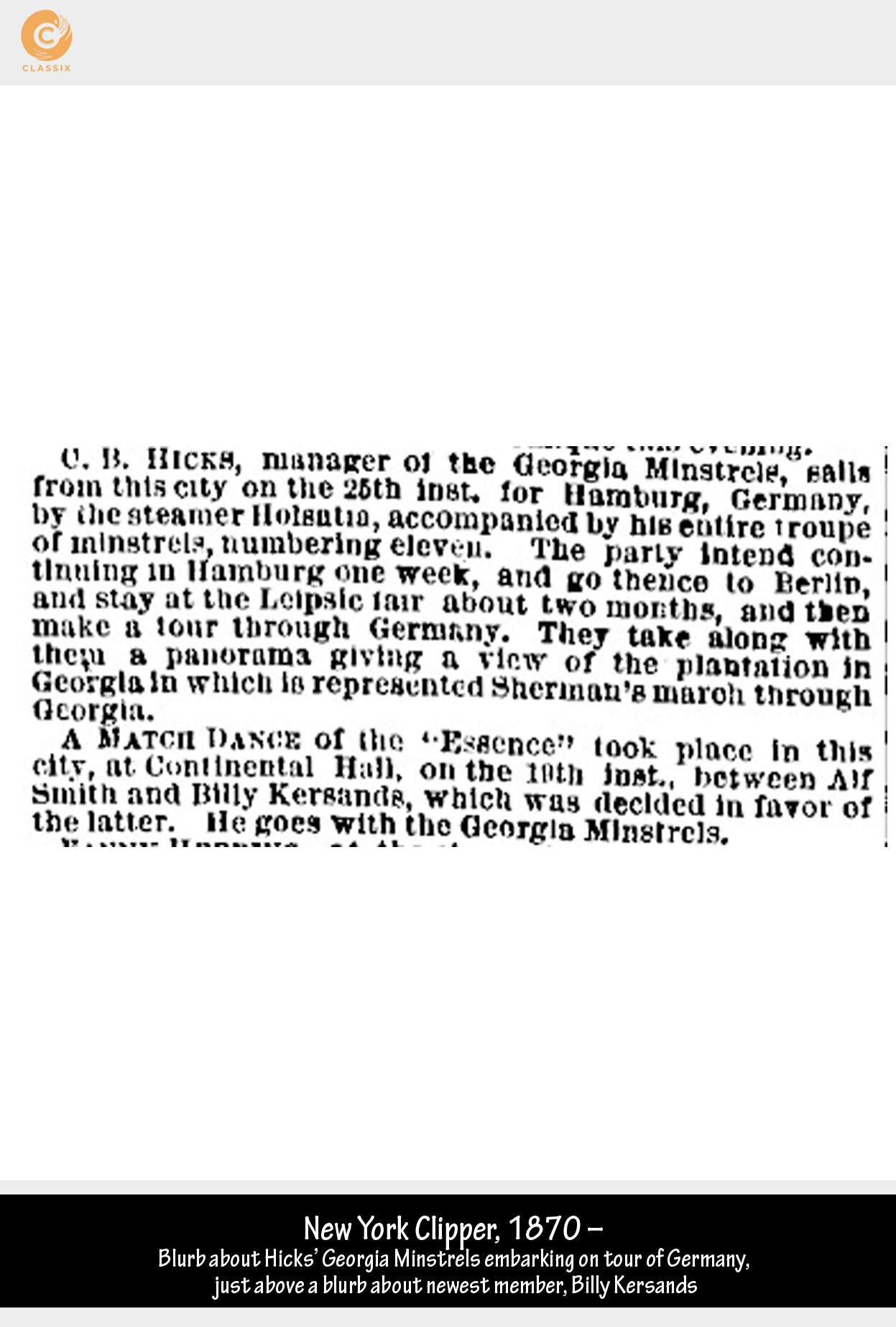

Although Hicks sometimes had off seasons, he did some good business. And In January 1870 he and the Georgia Minstrels set sail on the steamer Holsatia, bound for Hamburg, Germany. With them, they packed their set, which depicted a view of the plantation in Georgia - a view which included Sherman’s emancipating march to the sea.

When they landed in Germany, Hicks hit the ground running. He was a brilliant promoter, and soon word was appearing in domestic papers that the Georgia Minstrels were teaching the Germans to sing “Shoo Fly.”

Y’all remember that song, Shoofly? It’s not a tune that we really think too much about. But it’s a great way to remember that this time period that feels far away continues to reverberate in our lives today. At the time it was very common for musicians to hear a piece of music and start to include it in their own repertoire. They heard something then grabbed it and used it. There is a publication of the song Shoofly that went out in 1869 and people like to act as if that’s the origin of the song. But some people say they learned the song from Black troupes in the war. One tradition says Elon Johnson - who may have been born in Panama - taught it to some white people and they expanded upon it. Elon Jonson was a Georgia Minstrel. He may have come up from Panama but we know the Georgia Minstrels went to Panama in 1868. In any case, this was a tune that the Georgia Minstrels may have brought back with them from Panama. The song took off in 1869.

[Music excerpt: “Shoofly”]

But back to Hicks. When Hicks goes to England he joins Sam Hague’s troupe. At this point some of the original troupe members from Macon are now gone and some white performers have joined the troupe. So not only is Hague’s troupe now integrated, they’re also performing in blackface.

One can only imagine that that would have been quite the revelation and topic of conversation- these old troupe members seeing each other again for the first time, on a different continent, half of them now performing in blackface, the others not. What might those convos have been like, in some pub in England, in the fall of 1870?

In the fall of 1871, Hicks sets sail for the U.S., and sends notice announcing the triumphant return of the Georgia Minstrels.

CHARLES B. HICKS VOICEOVER “The Original and Only Georgia Minstrels, The Great Slave Troupe, Having completed their European tour, will make their first appearance in Pittsburgh for positively three nights only, in their original programme as performed before the Royal families of Germany and England. CHAS B. HICKS, Business Manager”

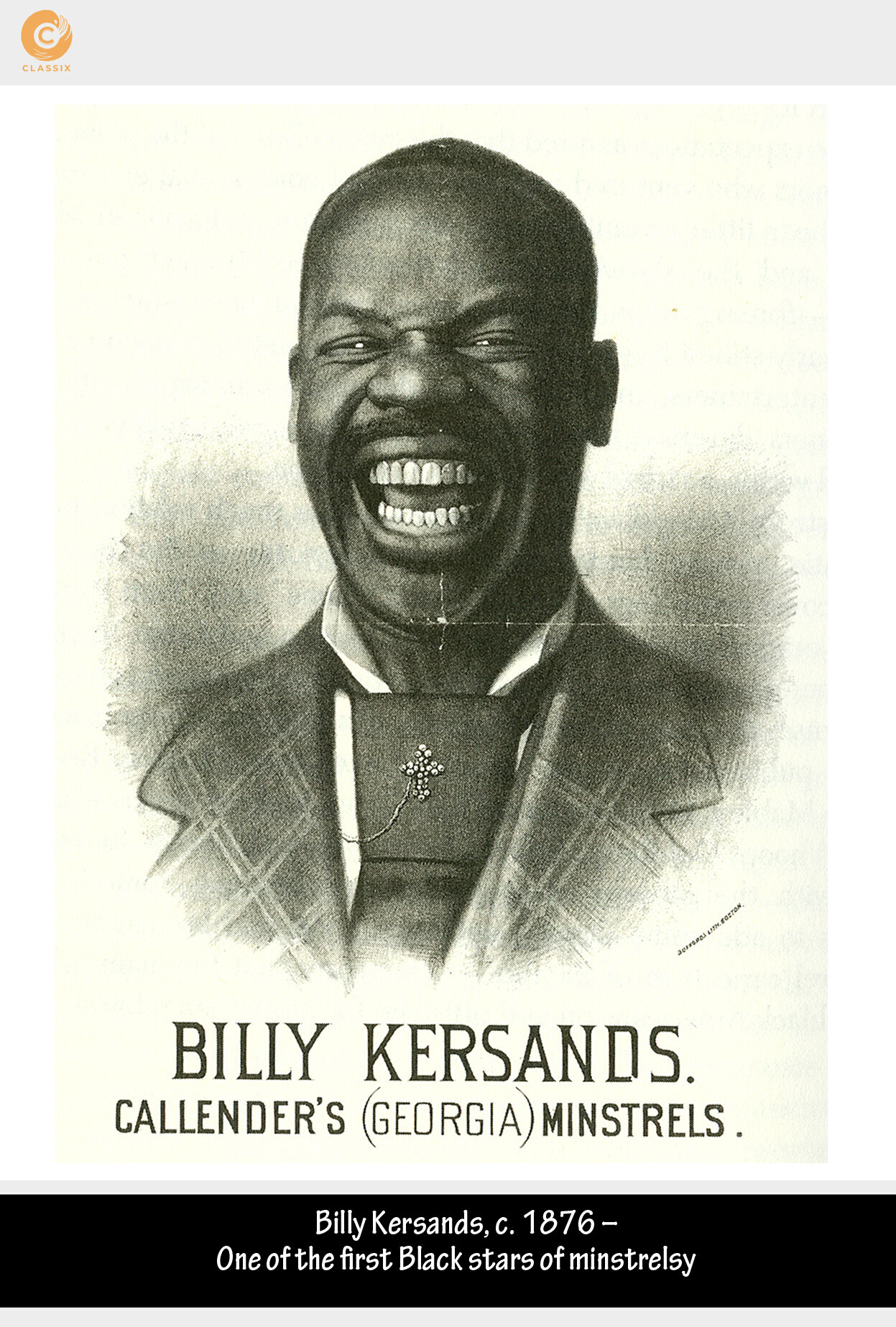

BRITTANY This new company does not seem to be performing in blackface. Hicks’ new lineup includes his old partner Bob Height; T. Drewette, a female impersonator; and a young comedian and dancer Hicks had discovered just before leaving the U.S., by the name of Billy Kersands. It also includes Aaron Banks, a popular comedian Hicks lured away from Sam Hague’s troupe in England. This greatly aggravated Hague and W.H. Lee (who perhaps also felt a stronger claim to the Original Georgia Minstrels brand).

Lee sends out a notice to the Clipper, “warning” the public that Hicks’ Georgia Minstrels are a fraud, and furthermore claiming:

W.H. LEE VOICEOVER

“This man HICKS was picked up while in England...and his abilities tested in almost every role in the minstrel profession in all of which he proved a “failure…’ Having no further use for him, a susbscription was taken up among the members of the troupe….to send him to America.”

BRITTANY Not to be outdone, Hicks responded quickly, citing numerous favorable reviews from the English and Irish press, and ending with one from Lee himself:

W.H. LEE VOICEOVER “Charles B. Hicks as Uncle Jasper displays talent of the highest order, and nightly convulses his hearers with laughter.” W.H. Lee

That argument came to a draw but it may have caused Hicks some damage. Though his troupe received good reviews, news records suggest they struggled to survive. This is not especially shocking; the renowned Fisk Jubilee Singers, who began touring in 1871 and would launch the international craze for Black Spirituals, also encountered incredible hardships, particularly in their early touring days. As Ella Sheppard, one of their original members, would recall:

ELLA SHEPPARD VOICEOVER “Many a time, our audiences in large halls were discouragingly slim, our strength was failing under the ill treatment at hotels, and on railroads, poorly attended concerts, and ridicule.”

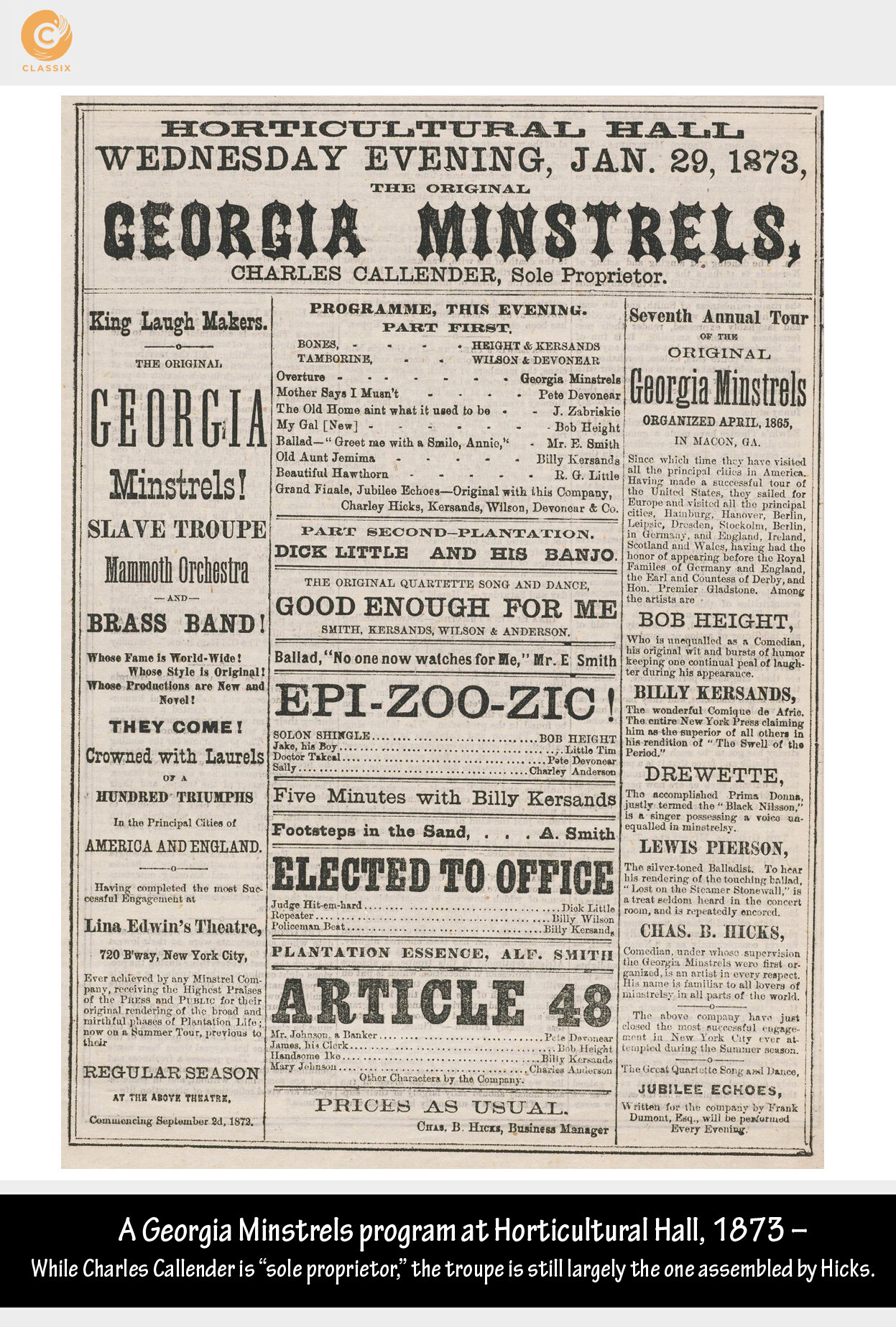

BRITTANY In April, 1872, a solution seemed at hand, in the guise of a new, white backer named Charles Callender.

At first Callender seems to be a fairly passive type of proprietor. A collaborator, if you will.

In this new collaboration with Callender, Hicks hires new talent, and it is like -here comes another sports reference- the formation of the 1992 Olympic Dream Team: The troupe doubled their end men, with Billy Wilson and Pete Devonear joining Bob Height and Billy Kersands, who would quickly become famous for his comic routines, most of which involved him riffing on how large his mouth was, and his incredible dancing. They would also recruit banjo player Dick Little, and “silver-toned” balladist Louis Pierson.

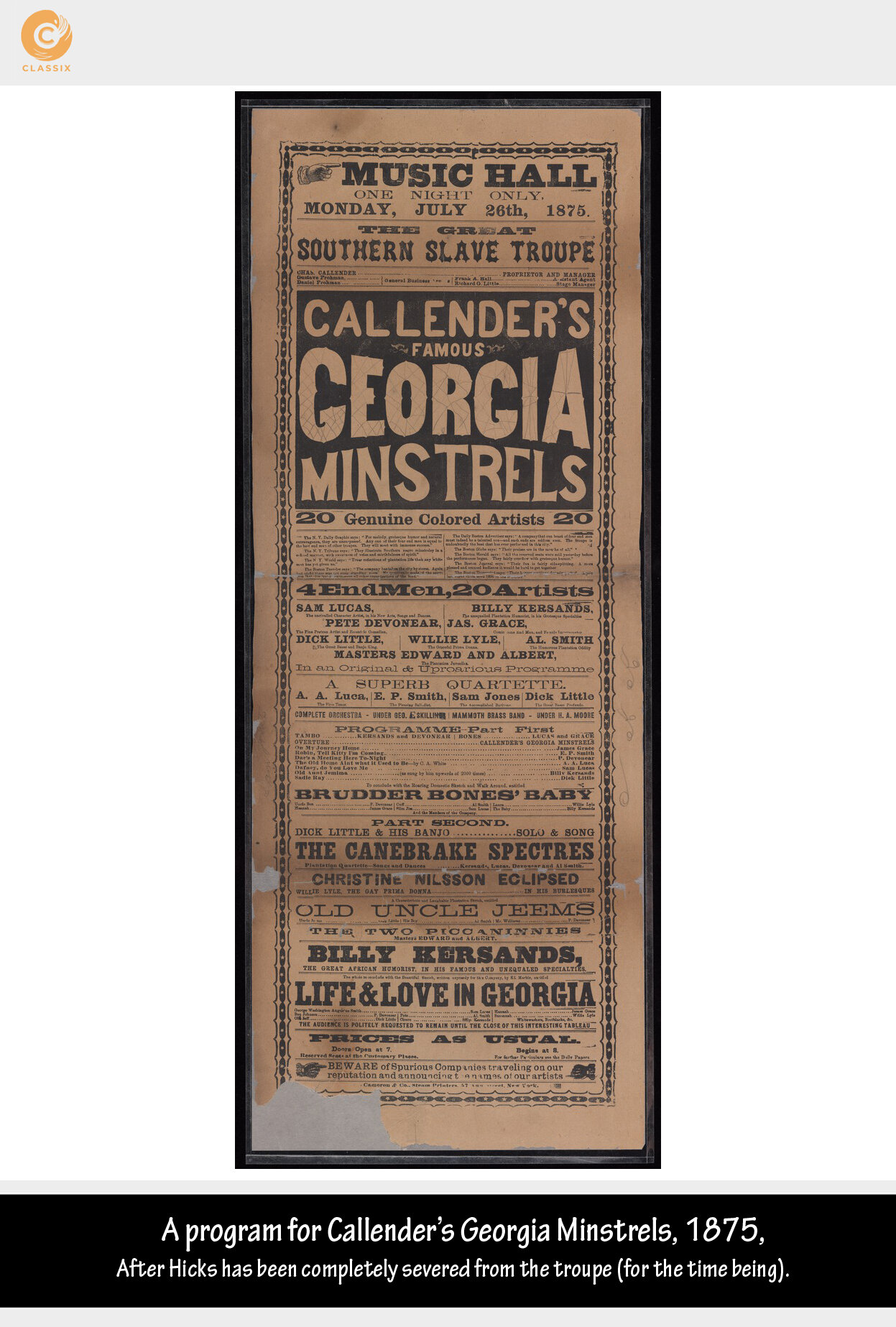

By April,1873 the troupe was rebranded once again. It is now called Callender’s Georgia Minstrels and it was the first time the troupe would bear a white man’s brand name in the US. It was under Callender’s ownership that the troupe became even more famous - in part, because Callender had access that Hicks couldn’t pull off despite his many gifts. Prior to Callender, the tours were mainly in the North and East. Callender expanded the troupe's performances to the South and Midwest. More and more audiences of all ages saw the show, because the Georgia Minstrels were also more family-friendly. According to Alain Locke, famed for his publication of The New Negro, the brand of humor from the Georgia Minstrels was more genuine, more clean, more alive, and the skillsets of the performers deeper and more varied than several of their minstrel counterparts. These components defined the Georgia Minstrels and led to an extraordinary and unprecedented level of success. This success, however, came at the price of Charles Hicks’ standing in the group.

And still: The Georgia Minstrels, under Hicks and then under Callender, as far as we can tell, through 1873, have not been and are not performing in blackface in the US.

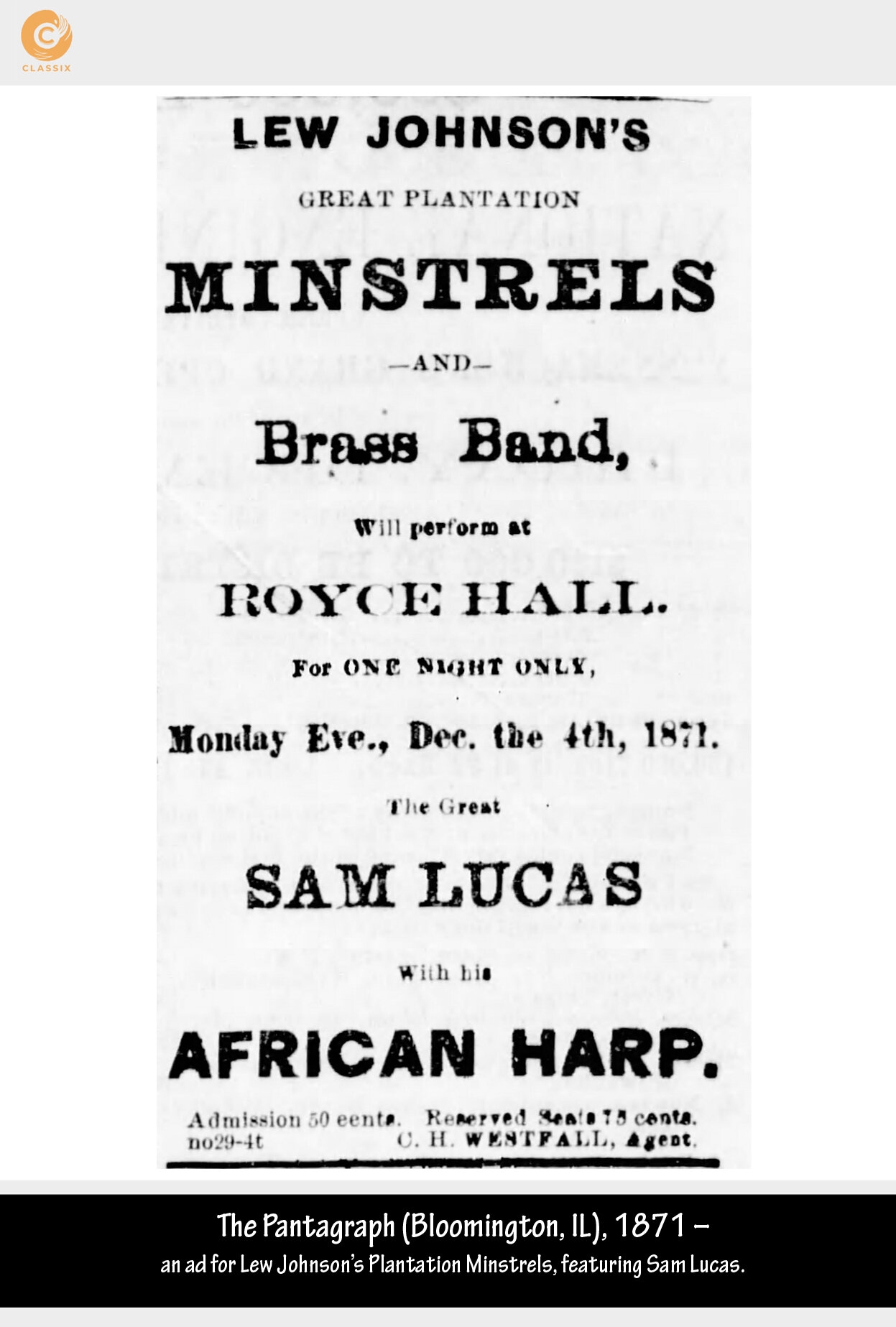

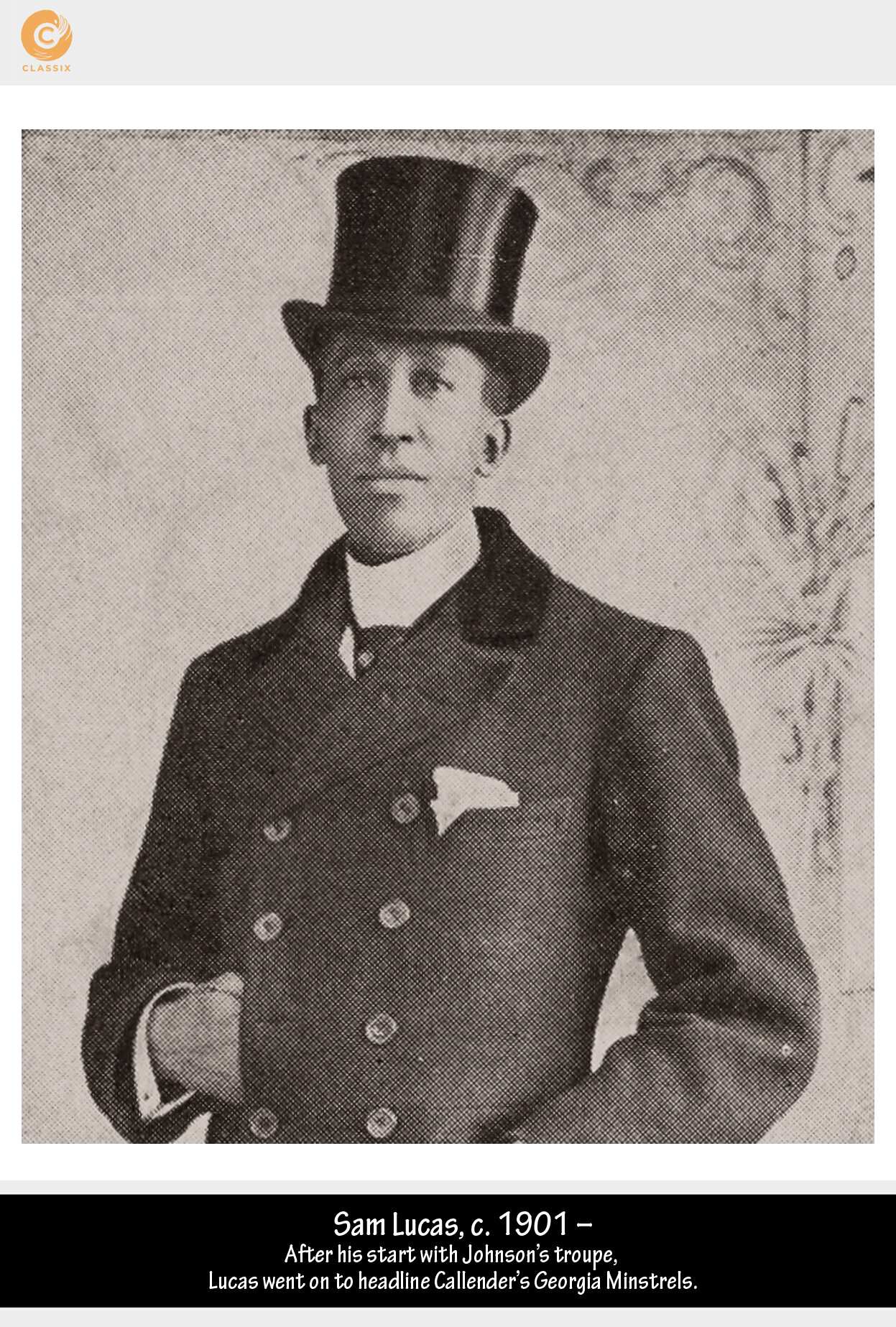

Hicks’s former troupe member, Lew Johnson, who joins the Georgia Minstrels for a short time, was a traveling man. Like the Oregon Trail settlers and Gold Rush 49’ers that came before him and epitomized American entrepreneurship and independence, Johnson journeyed throughout the West and Midwest, introducing and expanding minstrelsy nationwide. According to author Ike Simonds, Johnson and his myriad troupes spanned decades and employed more minstrels than any other minstrel troupe owner. Playing Six Degrees of Minstrelsy, all roads lead back, in some way, to Lew Johnson. In 1871, after at least one failed attempt at troupe-building, Johnson had his first successful season with the Lew Johnson Plantation Minstrels. And his breakout star was a man whose career ended up spanning nearly the entirety of minstrelsy: Sam Lucas. Sam Lucas was a veteran, having served in Ohio’s Colored Battalion. The child of formerly enslaved people, Sam grew up on a farm and was educated. Throughout his career he was known as a tall, handsome, exceptionally well-dressed man, a characteristic he attributed to his time as a barber. Barbers back then were known for being sharply dressed, and Sam was no exception. While working in this trade, he began teaching himself various skillsets: Singing and playing guitar and banjo among them. Not unlike Lew Johnson, Lucas, too, caught the traveling bug, and traveled most likely on steamboat up and down the Mississippi, teaching in New Orleans at one point, and later, landing in St Louis where he joins Lew Johnson’s troupe. As the 1871-72 season comes to a close, Lucas is itching for brighter horizons. He reaches out to Callender’s troupe, offering his services, and by July of 1873, the window opens and a position is given to Sam to join the famed troupe on their tour in Leavenworth, Kansas. At this point, the starting lineup for the Georgia Minstrels is pretty stacked. Sam finds himself riding the bench, doing a few funny bits here and there as he tries to find his place within the company. That summer he becomes the J Pierrepont Finch of minstrelsy, trying to climb the proverbial ladder a la How to Succeed in Business. He sings, but he’s not the greatest singer. He’s funny, but he’s no Billy Kersands. He tries to observe what holes the company may have and which skillset he has that would fill that hole the fastest.

And what Sam may have lacked in the songbird or jokester category, he more than made up for with a skill he had been practicing since his barber days: music. He had already tried his hand at writing his own, and as a way to cement himself in the troupe, he shows up at one rehearsal with a song he’s written, and all of the parts written out for each of the musicians. Quite an impressive feat. And the company agrees. Now, if they had realized that Sam had actually hired someone else to write out the parts for him, maybe they would have felt differently, but, as Sam saw it, the need was met. Wherever it came from. And the song itself was still his. His preparedness and quick thinking cemented him as part of them. This ability to constantly go to bat for himself would become a running theme in Lucas’ career. In fact, not long after this, he worked out a comedy skit involving him and the banjo player that he asked Callender to try out one night just to give it a shot, and the bit was in the act forever after that. It became one of their most popular gags. Within a year of this stick-to-itiveness, Sam Lucas becomes one of the headliners of the Georgia Minstrels. How To Succeed, indeed.

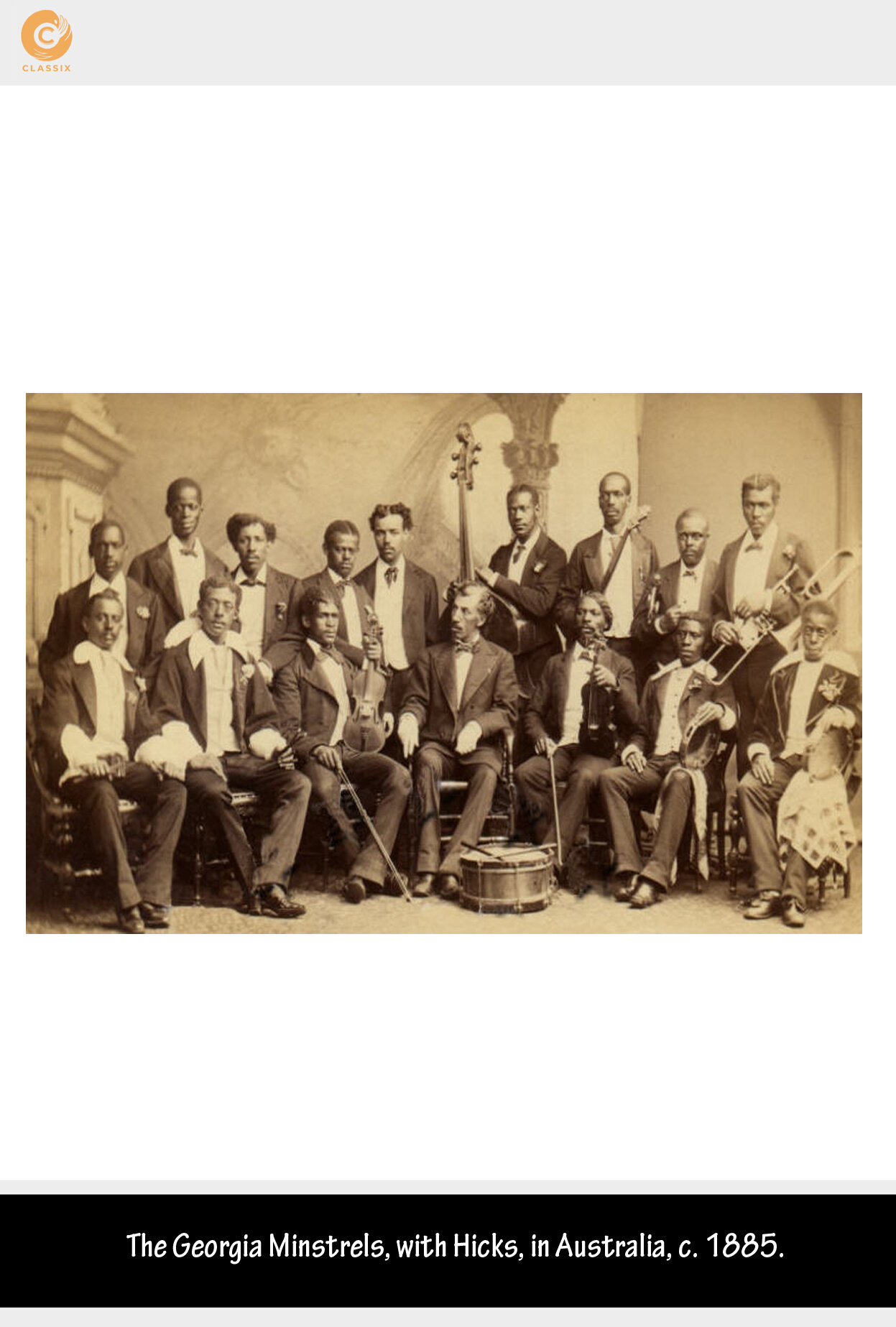

Now for full transparency, and not to take anything away from Sam’s hard work, there was a shakeup in the group, where Bob Height leaves, and helps create the space for Sam to move up. It is at this fulcrum that we see the beginning of the end of Charles Hicks and the Callender’s Georgia Minstrels. One way to look at it is that he is being constantly shoved aside, moving from the head of the troupe, to a manager, to an advance agent who is no longer touring with them, and then out of the group altogether. It’s also certainly possible that Callender pushed him out because there was a battle of who’s gonna be in charge. It also may have had something to do with Charles Hicks taking Billy Kersands on the road and calling the new group Callender’s Georgia Minstrels. It was a year-long struggle; Charles Hicks did not give up without a fight. But by the end of 1874, Charles Hicks was out of Callender’s Georgia Minstrels. And what did he do? He founded a new troupe - the Original Georgia Minstrels! And eventually, this new Original Georgia Minstrels would travel to the midwest, to the West Coast, and all the way to Australia and New Zealand - twice!

Change is occurring left, right and center. The only way to stay relevant in this business is to stay mobile. With everyone on tour, both locally and internationally, Black minstrelsy is entering the height of its fame.

At this point, you would be correct in assuming that the minstrel art form was not just dominated by, but exclusively composed of men. But that doesn’t remain the case. Quite a few women make a substantial impact to the way minstrelsy is presented, and popularized.

Next week we’ll meet two women who completely changed the game.

Thank you so much for joining us. For additional resources and images please visit theclassix.org and follow us on Twitter and Instagram. This episode was produced by CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience. Our sound editors are Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube. The theme song was composed by Alphonso Horne and the music was composed by Jeffery Miller, with a special banjo performance of Shoofly by Guy Davis and additional banjo performances by Arminda Thomas. See you next week!

GUEST BIOS:

Rhiannon Giddens

Rhiannon Giddens is a celebrated artist who excavates the past to reveal truths about our present. A MacArthur “Genius Grant” recipient, Giddens has been Grammy-nominated six times, and won once, for her work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a group she co-founded. She was most recently nominated for her collaboration with multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi, there is no Other (2019). Giddens’s forthcoming album, They’re Calling Me Home, also a collaboration with Turrisi, is due out this April and features songs of her heritage, sung to console her while she has been unable to go home to her native North Carolina due to the ongoing pandemic.

Giddens has performed for the Obamas at the White House and acted in two seasons of the hit television series “Nashville”. She has been profiled by CBS Sunday Morning, the New York Times, and NPR’s Fresh Air, among other outlets. She is featured in Ken Burns’s Country Music series, which aired on PBS in 2019, where she speaks about the African American origins of country music. She is also a member of the band Our Native Daughters with three other black female banjo players - and produced their album Songs of Our Native Daughters (2019), which tells stories of historic black womanhood and survival.

Giddens was recently named Artistic Director of Silkroad Ensemble, with whom she is developing a number of new programs, including The American Silkroad, an exploration of the music of the American transcontinental railroad and it’s builders. She has also written the music for an original ballet, Lucy Negro Redux (the first ballet written by women of color for a black prima ballerina), and the libretto and music for an original opera, Omar, based on the autobiography of the enslaved man Omar Ibn Said.

Giddens’s lifelong mission is to lift up people of color whose contributions to American musical history have previously been erased, and to work toward a more accurate understanding of the country’s musical origins. Pitchfork has said of her “few artists are so fearless and so ravenous in their exploration,” and Smithsonian Magazine calls her “an electrifying artist who brings alive the memories of forgotten predecessors, white and black.”