EPISODE 2

Hyers Sisters

Episode 2: The Alt-Minstrelsy Scene (1871-1897)

The voices and artists working outside of minstrelsy with a special focus on the Hyers Sisters, a sister-act of opera singers whose work revolutionized music and theater form, and the women they inspired.

Hosted by: Brittany Bradford

Guests include: Arminda Thomas (CLASSIX) and Susheel Bibbs

Produced by: CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience

Conceived and Written by: CLASSIX (Brittany Bradford, A.J. Muhammad, Dominique Rider, Arminda Thomas, Awoye Timpo)

Sound Design and Editing: Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube

Associate Sound Engineer: German Martinez

Theme Song: Alphonso Horne

Original Music: Jeffery Miller

Additional Music: “Goodbye My Cabin Home” by the Hyers Sisters (courtesy of Susheel Bibbs); “Carve Dat Possum” by Sam Lucas

+TRANSCRIPT

BRITTANY Hello friends and welcome back to the CLASSIX podcast, (re)clamation: an intervention in the current conversation around theatre history, where we recenter and uplift the black writers and storytellers of the American Theatre - both the celebrated and the forgotten. My name is Brittany Bradford and I am still your host for part one of our five part series, Black Performance in the Era of Minstrelsy. Last episode, if you recall, we focused on the early history and popularity of the Georgia Minstrels, particularly the performers and managers attached to them throughout their existence. Men like Charles Hicks, Bob Height, Lew Johnson and Billy Kersands. This week, the women take the lead as we lift up the artistry and legacy of Anna Madah and Emma Louise Hyers, also known as the Hyers Sisters who opened the gates for black women on the stage. With their troupe, the Hyers Sisters Combination, they became pioneers in the earliest iteration of Black musical theater.

This isn't just about the women taking the lead in the 19th century though; we are rocking some 21st century lady love as well, as I will be joined in this episode and subsequent others by Arminda Thomas, CLASSIX’s resident researcher, dramaturg extraordinaire, musician and president of the Sam Lucas fan club. We'll also get to hear excerpts from an interview Arminda and I had with performer and producer Susheel Bibbs, who has created two documentaries and a book about the Hyers Sisters.

So, Arminda, hi! As we've spoken about Black minstrelsy, we have seen that it's actually quite imperative that we have this conversation about research on Black artists from the past, and how, who tells the story, who transcribes it, who gets to be an authority on the narrative has just as much of an effect on its analysis and the way it's perceived as the story in and of itself? So, I am curious what it's been like researching the subject of Black minstrelsy on your end?

ARMINDA You know, we started and the libraries were closed. And eventually, we had a kind of workaround for that. But before we had that workaround, we just had to start with what was available, which turned out to be newspaper databases. And, and, you know, things that Digital Collections Online. And fortunately, the library did help us out by making a lot of things that normally you have to be physically at the library to access available from home. So that was - thank you, NYPL, you are fantastic and we owe so much to you

But the thing that that did for me, and for us is that instead of going immediately to the secondary sources, which are incredibly helpful, but often contradictory, and instead of starting there, there was a lot of just tracking and mapping that I had to try to do with the primary sources, which I think forced us to think about this in a different way. And, and I think that's ultimately been really helpful.

BRITTANY Are there any favorite discoveries that you've had so far? Through it all?

ARMINDA Yeah. So many fun discoveries that I've made. I mean, really, um, on some level, it's all been a bunch of fun discoveries, right, because so many of these people I'd never heard of and now I am fan clubbing them. You know, Sam Lucas, and the Hyers Sisters, and Charles Hicks. But I would say that one of the more surprising discoveries is the level of interest and popularity that Black entertainers had in the Midwest.

The number of news items that we found, that came in from Iowa, and Nebraska and Kansas, and Wisconsin, and, you know, just all of these places that we're not expecting, because we're generally expecting to be looking at the New York Clipper, especially for minstrelsy, the New York Clipper and the other New York papers and the Boston papers. But we're not really expecting the Midwest to be such fertile ground for research. And I think that one of the reasons for that is that, you know, in New York, there's a lot of entertainment to choose from. In Boston, there's a lot of entertainment. But in the Midwest, and a lot of these towns, you know, there are a couple of things happening, so they get a lot of press, they get a lot of excitement and when those entertainers come back, they really store the memory of their last shows. They really, they really just kind of take to them. And some of that spills over sometimes into personal interest in the artists. And on that note, one of my very favorite discoveries is one that I found just a couple of nights ago, and I'm going to save it for later in the program.

BRITTANY I'm so interested to hear your secret that I don't even know. So I'm looking forward to it. And I guess, Welcome to the hosting side of the podcast. And let's get the conversation going! Hyers sisters, take it away!

ARMINDA When I, when I think about the Hyers Sisters, I think about the Williams sisters - I am now going to steal from your fantastic tendency to, to contemporize with the contemporary analogy - and I would say I would think of the Williams sisters of Venus and Serena, you know, who as young girls showed this talent for tennis, and then their father particularly, their parents, but their father, just fed this nascent talent with a determination to ensure that they had every opportunity to you know, bring some black excellence into this sport that had been considered - Arthur Ashe and Althea Gibson notwithstanding - to be you know, a pretty white space.

So Anna Madah and Emma Louise Hyers were 19th century Williams sisters, only their talent was music, vocalization, concert singing. And at a very early age, the girls began singing duets and performing scenes from operas just for fun, to entertain themselves and their parents. Their parents, Samuel B. and Annie E. Hyers saw that their daughters had real potential, and being music lovers and amateur performers themselves, they decided to train them.

But within a year, the students had surpassed the masters so their parents leveled up. They got a German music teacher, they got an Italian former opera singer to teach them piano and vocalization, languages, intonation, enunciation, all of the things that you need to be taken seriously as a concert singer in that time.

And in 1867, the 12 year old Anna Madah and 10 year old Emma Louise made their professional debut to great acclaim at the Metropolitan Theatre in Sacramento.

So though the Hyers sisters were born in New York, they were, just like you Brittany, they were California girls. The Gold Rush drew their parents West soon after Emma was born. And as Susheel made clear, in our interview, the sisters ambitions were nurtured not only by their parents, but by the black community of the Bay Area, which though small was mighty and a hotbed of art and activism.

BRITTANY Part of the, the joy of going on this journey is getting the opportunity to meet people who've already delved into this research themselves. And one of the people who we had the pleasure to speak to was Susheel Bibbs.

Susheel is a singer, actress, filmmaker, scholar and author. And she's known for her recitals of rare musical works and has presented numerous masterclasses focusing on concert spirituals and black classical song.

SUSHEEL BIBBS The Hyers sisters, their community, and the arts community that was going on during that time. And when we talk to the Hyers sisters, we're really talking about when they became the Hyers sisters and that would start in about 1869. So to understand why they succeeded, you really do have to understand their community and you understand the politics of the time. The fledgling 19th century African American community in Sacramento, Stockton, San Francisco, Oakland was united by steamship line that ran between San Francisco and Sacramento. And there the steam stewards would bring messages back and forth. The important thing is that the, Anna Madah, her father was a barber and the barbers were the griots of the Sacramento community, and they passed all information that needed to be passed between communities to the community.

In Sacramento, the Franchise League and a, which was a group in San Francisco and Sacramento, they were working to get the right of testimony and by 1863 that law did pass so that African Americans could testify in court and it was at that time that the communities became really emboldened.

But before that they had what they called colored conventions in Sacramento and all people from all the areas would come and they set up newspapers and plans for schools. So we get that sense of people excited about their new rights. And in Oakland, they started a concert hall called the Mechanic's Hall. And that was where the Hyers, they sponsored in one of their first successful concerts. So they were, they backed businesses, they backed arts, they were famous sculptors, they were trying to say that they wanted the American dream.

And that is important because that's what the Hyers felt about their community. in Oakland, the community organized strikes and labor, for labor groups, they, the community sponsored, not only concerts, but they set the Hyers’ social compass. That's what the Hyers felt they should be talking about.

ARMINDA So in 1871, the Hyers sisters headed east on their First Transcontinental tour. And their parents had separated at this point and Sam Hyers gave up his barbershop to become their manager. Everywhere they went, it seems they drew crowds and great reviews, I mean, great reviews. So here's one from Beatrice, Nebraska:

“A very selecting critical audience attended at Hogs Hall last night to hear the Hyers sisters sing, and everybody went crazy over it, bursting out in ecstatic raptures and thunders of applause, piling up encore after encore, as if they could never drink enough of that exquisite melody.”

Critics raved about Anna Madah’s pure soaring soprano, about Emma Louise’s deep, rich contralto as well as her abilities with comic operetta pieces. And because Emma's range extended far down into the baseline, she could sing a male lead to her sister's female lead in romantic duets, which was a feature that historian Jocelyn Buckner calls “aural drag” and that charmed their audiences but it also made material available to them, which would not be available for black men and women to perform onstage together.

BRITTANY I love that. I love the element of drag. Even back in the 19th century.

ARMINDA On the East Coast, Sam Hyers expanded the group, hiring baritone John Luca, who was well known to New England concert aficionados as a former member of the Luca Family Singers, and Wallace King, a classically trained tenor from New Jersey. Boston critics who were famously hard to please proclaimed, “They are, without doubt destined to occupy a high position in the musical world.” In fact, the Hyers found the Boston cultural scene so welcoming that it became effectively their home base. And in 1872, the sisters were invited to participate in the largest musical happening in Boston, or anywhere for that matter, Patrick S. Gilmore's World Peace Jubilee, an international music festival, an 18 Day event featuring thousands of performers and choruses from around the world.

Emma, and Anna along with the Fisk Jubilee singers, who if you recall also began their first tour in 1871, led a chorus of 150 African Americans in a rendition of the Battle Hymn of the Republic. The performance, according to one paper, sent the crowd into a rapture of boisterous enthusiasm. The next few years saw the sisters settling into their lives as popular performers touring mostly in the northeast, but still with the national reputation, things were good for them. But the spirit of optimism nationally that had marked their upbringing and propelled them onto the national scene was giving way to a darker force.

SUSHEEL BIBBS But now we got to talk about not only Reconstruction, but you have to talk about post-Reconstruction, and that is directly what fueled the Hyers. So in 1866, right after the Civil War, the African Americans were so excited. They had land. They had congressional representatives. They had people running governments, local governments, and they had the troops standing there throughout the south and all these districts to protect them. They had voting rights by 1863. And so there, they even had a congress that overrode Andrew Johnson, and gave voting rights to African American men in DC and in the West. So this was a very exciting time for them. A cycle, however, of slow economic recovery came about and you'll start to see how this parallels things that go on today.

So in 1873, and ‘76, the economy began to slow and people saw immigrants in, into California as “other”. This always happens when people are suffering. They see the people who are different from them as coming in to take what they have. Ulysses S. Grant couldn't handle it. And in 1876, all of their political powers were on edge.

In 1876, the ability of the electors to elect a president broke down. And so there ensued a deal with a man named Rutherford B. Hayes who had been sympathetic with African Americans, but it's a strange thing when you get power. And so they made a deal with him. They said if he would just pull the troops out of the South then he could become president. And that's what he did.

Well, all hell broke loose. The removal of protective troops caused by racial backlash of hatred, which exists today.

BRITTANY Thank you so much for joining us for this conversation about the legendary Hyers Sisters. Again, my name is Brittany Bradford, here with Arminda Thomas. Let’s jump back into the conversation.

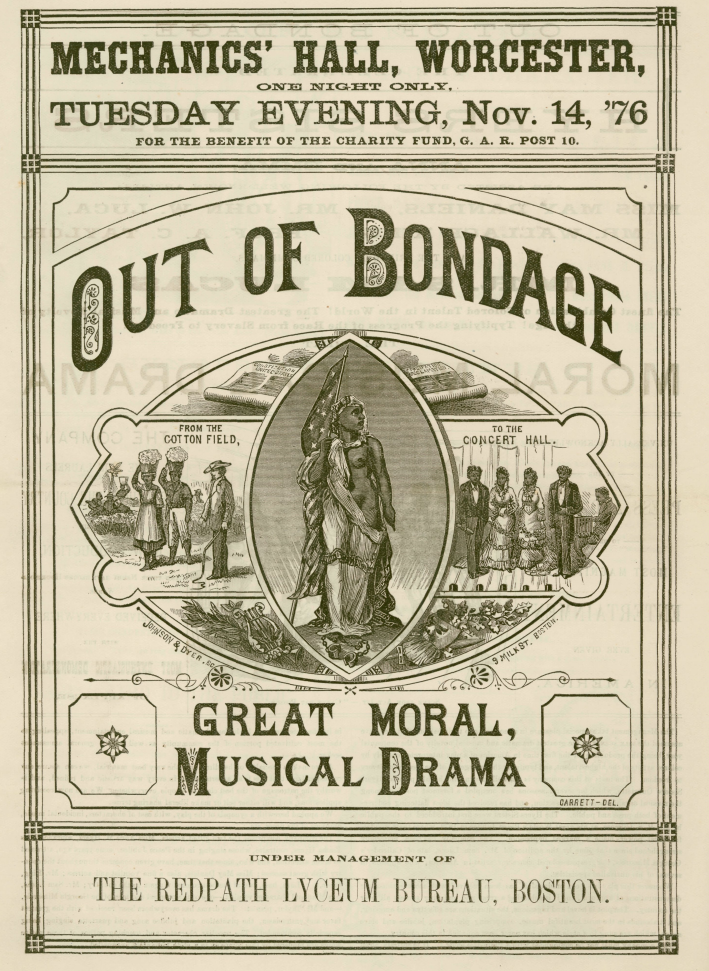

ARMINDA In 1875, The Hyers sisters secured a famously respected agency, Redpath Lyceum, who had represented such speakers and performers as Mark Twain, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, so a really, a top notch group. And shortly after, it was announced that Redpath had hired - commissioned - Joseph Bradford, a southern white man turned union soldier to write a play for the Hyers chronicling a family's journey from slavery to freedom.

Originally titled Out in the Wilderness, it became more widely known as Out of Bondage. To round out the company, the Hyers swiped Sam Lucas, who at that point had become famous as a comedian and balladeer songwriter from Callendar's Georgia Minstrels. And seriously when I say swiped, he was--one week, Callendar's was announcing the whole season with him as a headliner. And the next week, he was hanging out with the Hyers sisters.

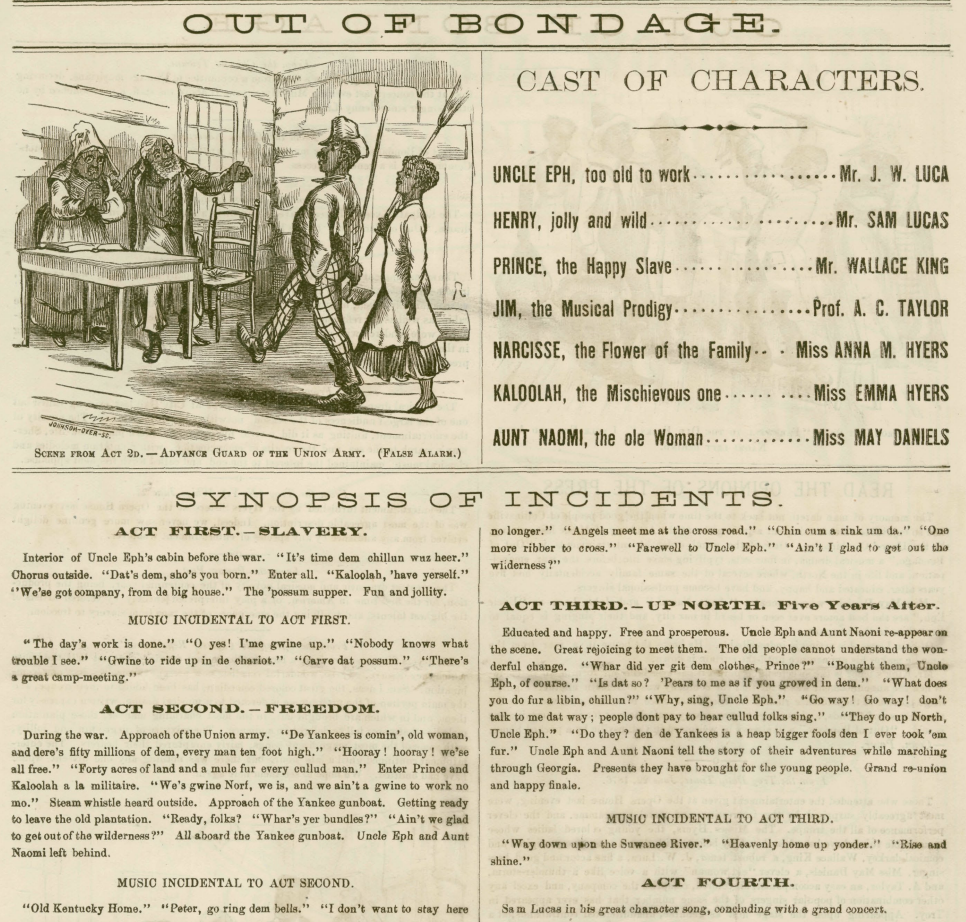

Out of Bondage was labeled a great moral drama in the spirit of early non-minstrel productions of Uncle Tom's Cabin. And that's born of the idea that drama can and should inspire moral feelings and behavior in its audience. Structurally, it had three acts and the first was a family, an enslaved family gathering at the end of a long day to share a meager but delicious meal of possum.

The possum being specific because Sam Lucas had a very well known song called “Carve that Possum” and they wanted to include it in the play. So possum was the meal.

In the second act, we had freedom. The Union troops came, the white owners fled, and the family was freed. Young people decide to go north and the old couple remain on the plantation or plan to. And this piece is notable because it included Sherman's March to the Sea. Like Hick’s Georgia Minstrels and also, because they had this march to the sea, it allowed them to get participation from the audience.

And then the third act is, happens years later, when the old couple who had followed Sherman's March after all, then decide to come and see their children and find that they have settled in Boston, they're all living well, they're gainfully employed as Jubilee singers, and speaking perfect English. So that is, that is the moral part right?

BRITTANY Here’s Susheel Bibbs again -

SUSHEEL BIBBS And this is what's started the Hyers. Remember that the Hyers, we can know that the highest we're told that African Americans were seeking the dignity of the American dream. And yet, this was not the picture in most minds of, you know, whites continued to wear the black face mask in performances that would serve to define the meaning of blackness by all or most Americans who had little contact with blacks. And that is a quote by Dr. Errol Hill.

So what happens here is that they see that that is the image that's out there. They know that they are important in white theater, and they decide that they're going to use their clout and go back to their audiences and they did so for 20 years, and bring them a new vision of African Americans to try to counter what was going on, with the denigration of their people.

ARMINDA So it's showing that that freedom, and this life in the North has tamed, has made all of them better people and prosperous.

And at the end, there was a coda, which was a time for a character song. And the character song was usually sung by Sam Lucas. And it was almost always, at least for the first um, the first couple of years, it was almost always his rendition of My Grandfather's Clock.

SUSHEEL BIBBS They brought hits into their show because it was, it was very malleable, you could--as long as you could support a part of the story, you could put any song there. So what started as just spirituals became enriched with the music of the times, which was Gilbert-and-Sullivan-like music, and all the pop hits from the times, which had to do with the things that Sam Lucas was doing and others, so the people flocked.

Susheel: Their audiences flocked to this first of all. They love the Hyers. Opera audiences are very loyal. Secondly, they love the stories. Thirdly, they realize that you know, they could relate. For the very first time they created Black leading characters on stage. And, and these audiences could relate to what they were doing.

ARMINDA It was a really big hit. The management had to take out ads warning against companies purporting to produce plays with the same or similar titles. The Hyers sisters, and later, a separate company run by Sam Hyers, which we will get to, toured with the play on and off for about 20 years.

BRITTANY I think it was you actually, who coined the term alt minstrelsy when we were trying to figure out what to call this special category of performers like the Hyers Sisters who weren't necessarily operating in the same mode of minstrelsy that we saw from minstrel troops in episode one. So can you talk about what you mean by alt minstrelsy?

ARMINDA Yeah. Alt minstrelsy to me is it's like a riff on music. So you have alternative rock, alternative country. Alt. And it's generally used to describe songs and artists who aren't really in the mainstream of something. It is in the conversation but it is not quite the thing or there's something that deviates, that makes it feel kind of outside.

Usually it's, like independent, like independent artists would be, are often also alternative. So if you think about this 19th century setup, where minstrelsy is the mainstream - It is, in fact, perhaps the first American mainstream entertainment - and blackface, representation of blackness, is a defining characteristic of minstrelsy.

So on some level, the first black minstrel troops, you know, that Hicks's group, obviously, would might fall under the, the traditional, like I'm naming it and therefore the traditional alt-minstrelsy title, because they're performing without, if they're performing without burnt cork, then that is outside of the mainstream.

But then also, because minstrelsy has cornered the market on performing blackness that is, that is what the audience kind of comes in thinking about when they see black bodies on stage. Then even performers who are not performing with the thought of minstrelsy, who are consciously attempting, as the Hyers sisters were under Redpath and through their life to be anti-minstrel in terms of the show, in terms of what they want to present. Even they, and classical performers like Elizabeth Greenfield or concert singers like the Luca Family Singers, or Blind Tom, they're going to be alt-minstrelsy, because they are, by virtue of being Black, they're in conversation.

And once Black minstrel troupes begin touring, that stream gets even murkier because other Black performers often get put on the same bill, on the same bill. So the Fisk Jubilee singers who are singing, classically arranged renditions of black spirituals are sometimes billed as minstrel troupes in white papers. When, when I'm looking through, we're finding white papers will call them, you know, “this minstrel troupe out of Tennessee,” They're not a minstrel troupe. They're not performing minstrel shows there, it doesn't have that structure, but they are Black people singing, they’re a minstrel troupe.

So the Hyers sisters, even though they and particularly their agent, Redpath, took care in the billing, you know, said, this is not, this is no minstrel show that - but they're in that stream, they're in the stream. And not only that, there's sometimes they play on the same bill as minstrel troupes, sometimes. The month that Sam Lucas jumped from Callendar’s to the Hyers was the same month that the Georgia Minstrels and the Hyers Sisters performed together in Boston; in fact it might have been that very week that they say, “Hey, come join us” and he jumped so… And then when you have, you know, members who float from one to the other, that all becomes, you know, it's just, it's just very blurred.

It's not a judgment, it's just an observation. This is a thing that they're contending with.

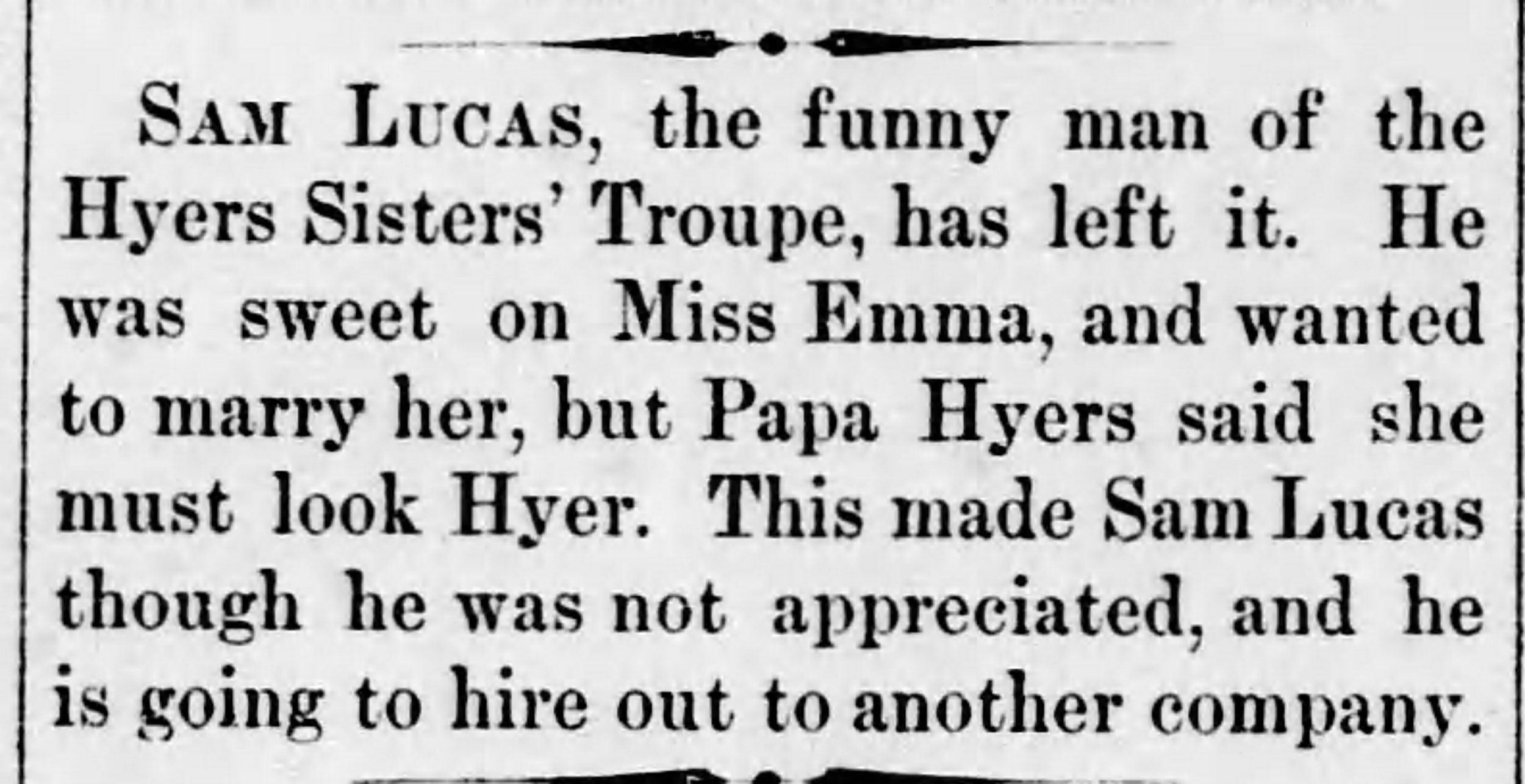

In 1878, just as quickly as he came, Sam Lucas was suddenly missing from the Hyers Sisters combination. And now we have some 19th century hot tea. Because this time, he did not quit and bounce. He apparently was bounced, and newspapers around the country--this is not an exaggeration--newspapers around the country, not hundreds, but like dozens had speculation on what had happened. And they all came to one conclusion.

And that conclusion was that love was at the heart of Sam's sudden absence. Yes, a showmance. And this is particularly hot tea from the Cedar Falls, Iowa Gazette, yes, Cedar Falls, Iowa.

“Council Bluffs non pareil brings out this new version of the love affair of Sam Lucas and Emma L. Hyers. Last fall, when the Hyers sisters appeared in this city in their play Out of Bondage, the indications were that Sam Lucas the colored comedian of the troupe was slightly, if not considerably gone on Miss Emma L. Hyers, the vivacious contralto. We have lately noticed by an exchange that appearances were not deceptive in this case. And furthermore, that Sam's tender passion for the dusky creature touched a sweet responsive chord in her susceptible breast. But the old man Hyers kept a watchful eye over the young folks, and looked with high disfavor on the mutual yearnings of the mirth provoking Sam and the sweet voiced Emma. The sequel to this romance in real life occurred in Peoria the other day, when Sam and the girl attempting to go before a preacher and have the knot tied, but the old man Hyers got wind of it, and issued his writ of injunctions and put the girl under surveillance.

Fearing that this might not have the desired effect, the old man went further and bounced Sam out of the company, and he has no one to do character songs for him, as Sam has stopped short, never to go again till the old man Hyers dies,”

So this abrupt separation caused both Lucas and the Hyers to flounder a bit, though they managed, both of them to stay productive, and we'll talk about Sam's work later, but the Hyers recovered by wooing an even, arguably, bigger star from the minstrel stage, comedian Billy Kersands to take Lucas's place.

And they added another new play to their repertory called Urlina, the African Princess. And this is the first play as far as we can, as far as we have found so far, to tell an African love story. The title character, the African princess Urlina is played by Anna Madah and the prince who falls in love with her is played, not by Billy Kersands, no, but by Emma Louise. Kersands played seven different characters, and all of them funnier than the last one. And, and the reviews were pretty strong, but the piece doesn't seem to have resonated the way Out of Bondage did. There's a book by Ike Simon, a man named Ike Simond, who we only know because he wrote this book, which is called Old Slacks, Reminiscences of the Colored Profession. And it's his attempt to tell the story of Black people performing from ‘bout 1865 to 1891.

Though it's written, it feels so much like an oral history, because it's really just one man who has been involved in this profession trying to tell the story as he remembers it from you know, bills that he may have, but often on his recollection, which is to say, as you know, you might know when you ask your grandparents about things, there may be some things that are not quite, according to Hoyle, they're not quite right.

But the general feel of it is right, you get the, you get the, the under the idea of, you know, how many people really are performing and, and kind of what people thought about them at the time, sometimes, particularly for Charles Hicks and Lew Johnson, and Sam Lucas, and the Hyers sisters, he talks about the Hyers sisters. He says they were the best show he ever saw. And that's another way of looking at it when you talk about, we talk about the mainstream as being minstrelsy, but, in his framing the mainstream for, for Ike Simonds, and perhaps for them to are black people trying to be artists. You know, it's, it's, it's the beginnings of, you know, they're not all in the same place. They meet sometimes in cities, you get more two or more groups together, and they get to vibe off each other and then go their separate ways. But it's, you know, it's this movement towards the idea of a community, right.

And then, in 1883, after they've been dropped by Redpath, Emma, Emma and Anna separated from their father, who had married a company member, the former May C. Daniels, who was many years younger, kind of a contemporary of the, of the daughters, and seemed poised to use her as a replacement for Emma Louise.

We're going to move from Emma Louise and Anna Madah, to Madah and Louise because as they got older, that is how they began referring to themselves professionally.

So they split with their father, their father built a company called the Hyers Colored Concert Singers or the Hyers Colored Combination. He dropped “Sisters,” but it was so close that um…that scholars found it really hard to understand that there were two troupes at this time, that there were two Hyers groups going and so the Hyers Sisters are sometimes credited with things that were done by their father's company.

But after Sam and May go their way, that would be Sam Hyers, not Sam Lucas, but after Sam and May go their way, the sisters are sometimes forced to work more, more closely with minstrel troupes.

They convince the Callendar Consolidated minstrel troupe to do Uncle Tom's Cabin in San Francisco. So Emma, Emma Louise married the bandleader during a performance of Uncle Tom's Cabin in San Francisco. And then Anna, the next week, married another member of the band.

So they were really intertwined in this life, and they continued to perform sometimes with minstrel troupe manager types as their managers, sometimes they sang, you know, they did Jubilee songs or songs as part of the troupe but not performing with the troupe. In 1892. Charles Callendar briefly came out of retirement. Yes, that man, old man Callendar, came out of retirement to act as the Hyers sisters’ agent, and that was for their last big tour, which ended in 1893.

And after that, the Hyers sisters officially retired as a company, though they were not quite done as performers.

You know, we've talked about - that women were largely absent from black minstrelsy, that's why female impersonators were so necessary.

When women were included, for instance, a group called Haverly’s Colored Minstrels toured Europe in a large troupe, a huge troupe and there were many women included in that number, but they were strictly Jubilee singers.

And those women were segregated completely from other sections of the show. But the Hyers as performers helped expand opportunities for Black women on stage.

And also, I guess, indirectly, for Black women as writers, because one of the first offspring of this was Sam Lucas, who after he left the Hyers so abruptly, had this determination to form his own troupe, he did not want to just go back to being in Callendar’s or Sprague’s.

He really wanted to have the thing that he had had with them. And so he formed a group, the Sam Lucas Combination. And he commissioned a playwright, Pauline Hopkins, who was a singer herself, a performer from Boston so she was influenced by the Hyers sisters who, you know, that had been their home base, and she was definitely influenced by them and had seen them.

And speculation is that, you know, she did some of their writing for them, though we can't find those scripts to say that that's absolutely true. After Sam's detour through Uncle Tom's Cabin, he made good on his determination to form his own troupe with a play written for him. And that piece was called The Underground Railroad, later known as Peculiar Sam by Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins.

And that made hers, the first play by Black woman to be produced and published. And that is a piece that is in conversation with Out of Bondage, as you might guess, it's called The Underground Railroad.

Therefore, it is a story about moving from slavery into freedom. However, it is a play about escaping from slavery into freedom. So it's much, much higher on the agency note.

It has a lot of the same kind of stock characters in that it has a house, a character who would be played by a person like Anna the soprano, who's kind of the more cultured house, house servant, a wilder character, like the kind who would be played by Emma. But it's also in conversation with another play that was never performed, but was read a lot on, in abolitionists circuits called The Escape by William Wells Brown.

And then furthermore, in later on, in 1890, Sam collaborated with a white backer called, named Sam T. Jack to create a show called, The Creole Show, and that was really, by most accounts, Sam's brainchild, Lucas that is.

But it was really Sam's brainchild that you know, he got money to kind of put together as he like. Now it was structurally a minstrel show. It had this, the opening act, the olio, the end instead of being a skit was this burlesque which is to say it was women dancing but not the burlesque that we have come to think of as burlesque. It was just women dancing, but they also had women in the first part and then the second part acting as interlocutors in drag dressed as interlocutors too.

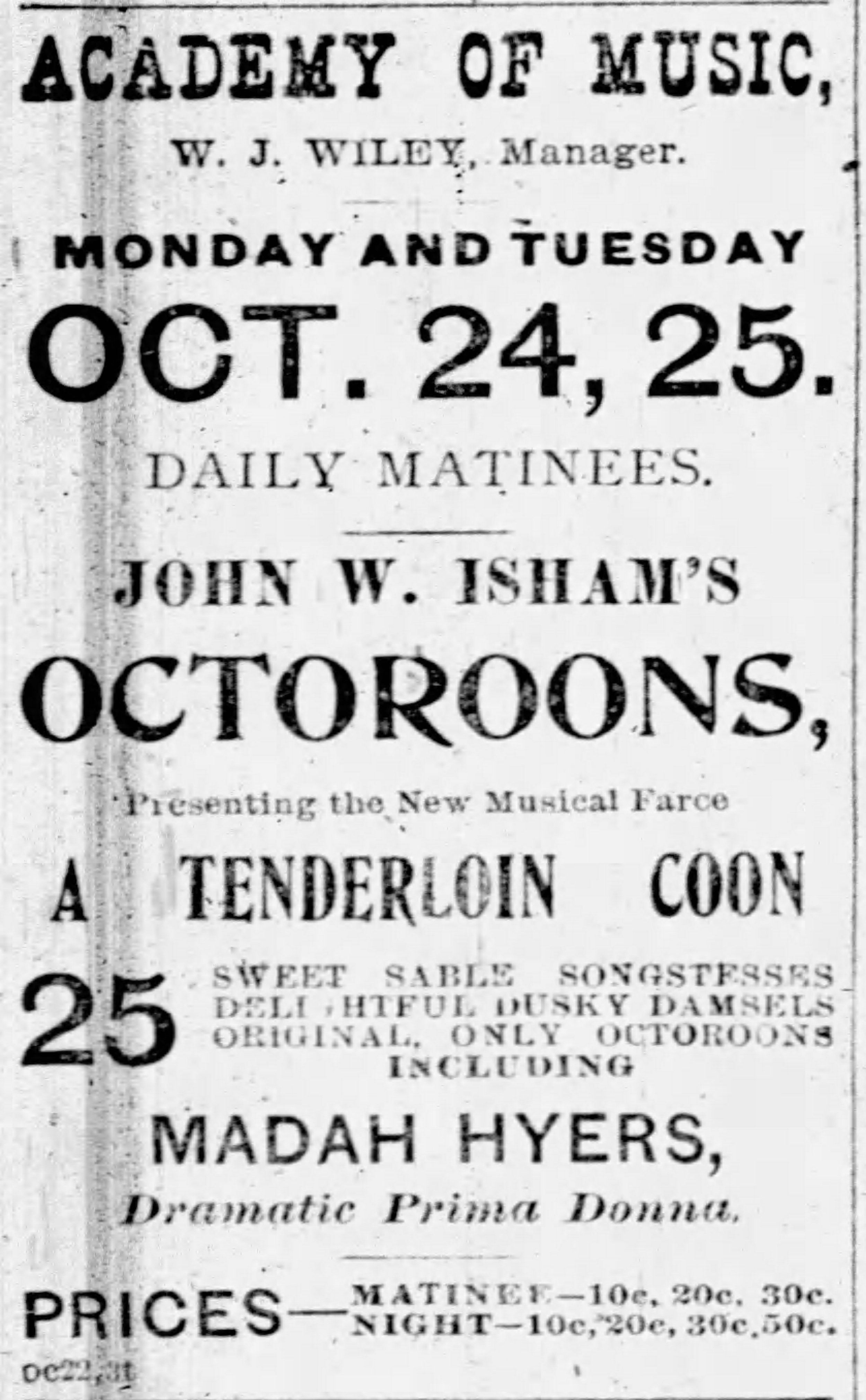

And after the Creole Show, there was a show called The Octoroons. The Creole Show’s Black advanced agent John Isham left in 1895 to create his own show, which expanded performance opportunities for women again. Now this show prominently featured the Hyers sisters, particularly Madah Hyers, who stayed with the show until 1899.

And she stayed mostly as a singer, but Emma, when she was there performed in skits. And that is another expansion because in addition to being, you know, interlocutors or doing that, they also became, more and more we're seeing women, as actual performers in the skits.

John Isham was a Black advance agent who was running this show. And of course, wherever you see a black man running something, you will see some white folk trying to jump in on that. And in this case, two white men got the idea to, to come up with something to run in competition with Octoroons.

And they, they hired to headline this show a woman named Sissieretta Jones, who like the Hyers before her was a trained opera singer who had been acclaimed who, you know, had great reviews, but was struggling to make it on, on the circuit.

After years on the concert circuit, she was offered this headlining role in this show that was designed to compete with the Octoroons and, and she performed only in the last act. The third part was her coming out and singing arias.

But even so, this, this company was important. A) because it featured Sissieretta Jones. It also expanded opportunities for women, and as singers and dancers and actors. In particular, Black Patti Troubadours is the place where we last see Emma Louise Hyers. She goes to join that when she leaves the Octoroons.

And in 1897, she comes in and then she disappears and as far as we know, she passes away in 1899. In a symbolic perhaps passing of the baton, the Black Patti Troubadours is also where we first meet Aida Overton who is a dancer, a choreographer, a performer, and who will have a very important role to play in next week's episode.

BRITTANY Yes! And Black Patty Troubadours had another up-and-comer in their midst, who was a featured performer and skit writer by the name of Bob Cole, who would be instrumental in the next phase of black theater. As we've said before, you know, we each have our own fan club for different performers operating at this time. You heard some Sam Lucas love earlier from Arminda. I would be remiss if I didn't give a little teaser here to a man whose vision that I've really grown to admire in this process, Mr. Bob Cole.

He was a man of many talents, as many of the artists of this time were. He wrote, he performed, he advocated for himself and his fellow performers. But I think what I love most about him was the awareness he had in the power of owning what you create. And we're going to see a lot of that in this next period of minstrelsy.

As we enter the early 1900s and minstrelsy shifts yet again, we see people really taking on a responsibility for the art they create and the people with whom they collaborate. Collaboration and education really are the modes at play and we'll be investigating that in more depth by looking at two iconic duos: Williams & Walker and Cole & Johnson & Johnson. We'll get to that. We will also be looking at how the artists at the turn of the 20th century fought to create a space for black theater excellence and examine how successful that venture was.

So, until next time, thank you for listening. Thank you to Susheel Bibbs for her time. And be sure to check out her film Voices for Freedom, the Hyers sisters’ legacy on PBS. And thank you, Arminda! Thank you for this conversation. Thanks for joining me. Thanks for your wonderful insight. If you want to go even further down the rabbit hole and be a researcher in your own right, please check out our website the classix.org that's theclassix.org for further images and resources. And be sure to follow us on Twitter and Instagram @itstheclassix. This episode was produced by CLASSIX and Theater for a New Audience. Our sound engineers are Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube. The theme song was composed by Alphonso Horne. The episode music was composed by Jeffrey Miller. See you next week!

GUEST BIOS:

Susheel Bibbs

Singer-actress-filmmaker Susheel Bibbs (Susheel) -- a graduate of Boston University School for the Arts and The New England Conservatory of Music -- has served the Arts and Humanities for over 30 years. Acclaimed internationally in opera and in concert, Bibbs is also a national Emmy winner and was once the youngest Executive Producer in the PBS system for a major international series. Recently, her films on unsung African-American heroine have won 17 international, film-festival awards and two international Telly’s. And Two have screened on PBS nationally. In 2012 she founded The Living Heritage Foundation to help expand the careers of other professional artists who have contributed to the Arts and Humanities.

Bibbs has recently received a Lifetime Achievement Award from Marquis Who’s Who Among Women, a profile on PBS Arts Showcase, the Willis Patterson Award for research in black classical song, and The San Francisco’s Supervisors’ Highest Commendation for her work in the Arts and Humanities. Two of her films – Meet Mary Pleasant, Mother of Civil Rights, and Voices for Freedom – The Hyers Sisters’ Legacy are screening on PBS; the Pleasant film is also available for rental or purchase on Amazon Prime Video. See www.susheelbibbs.com and www.TheLivingHeritageFoundation.org

EPISODE 2 GALLERY

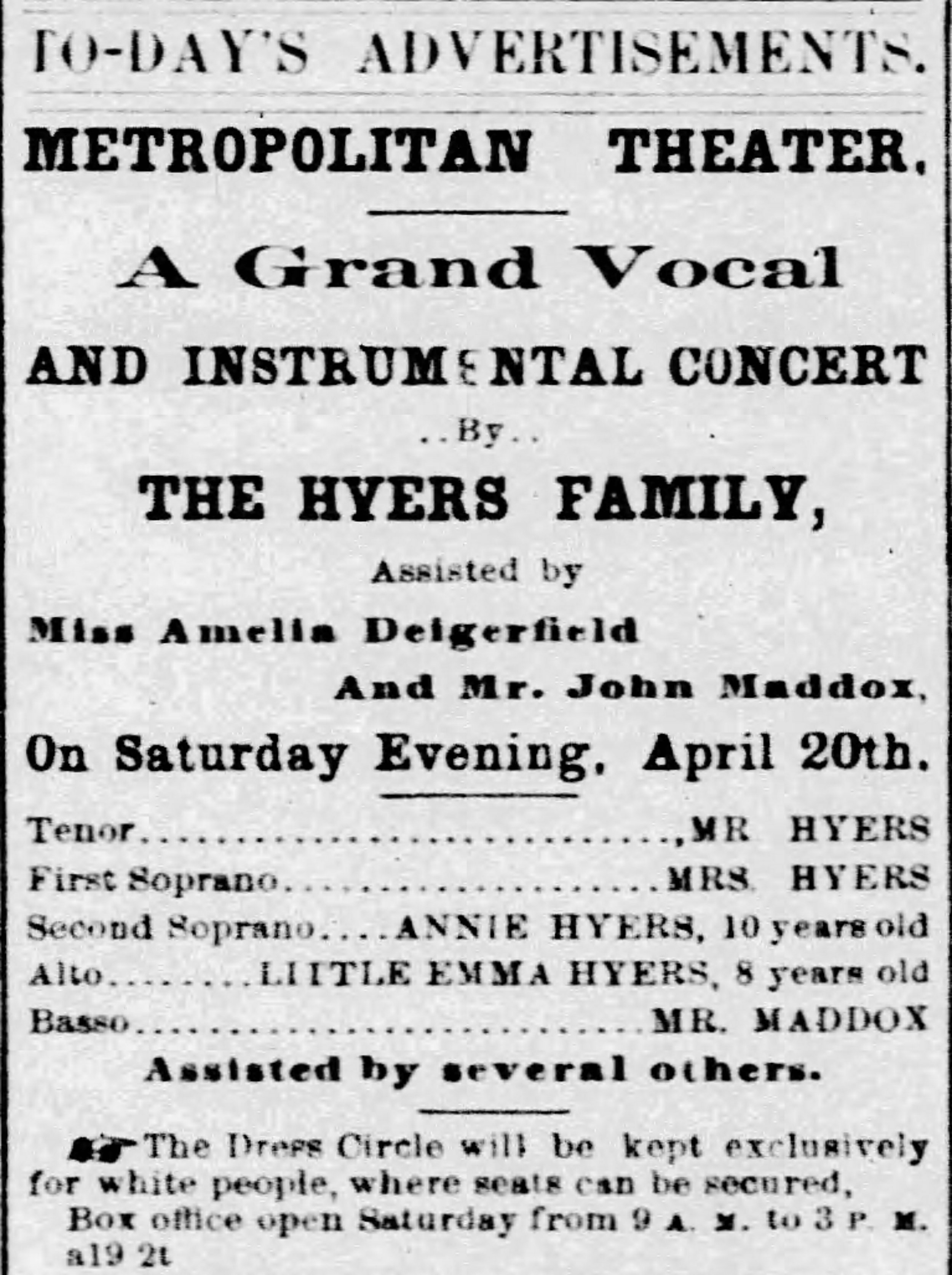

Sacramento Daily Bee, 1867: An advertisement for the Anna and Emma’s first public performance (with their parents as The Hyers Family).

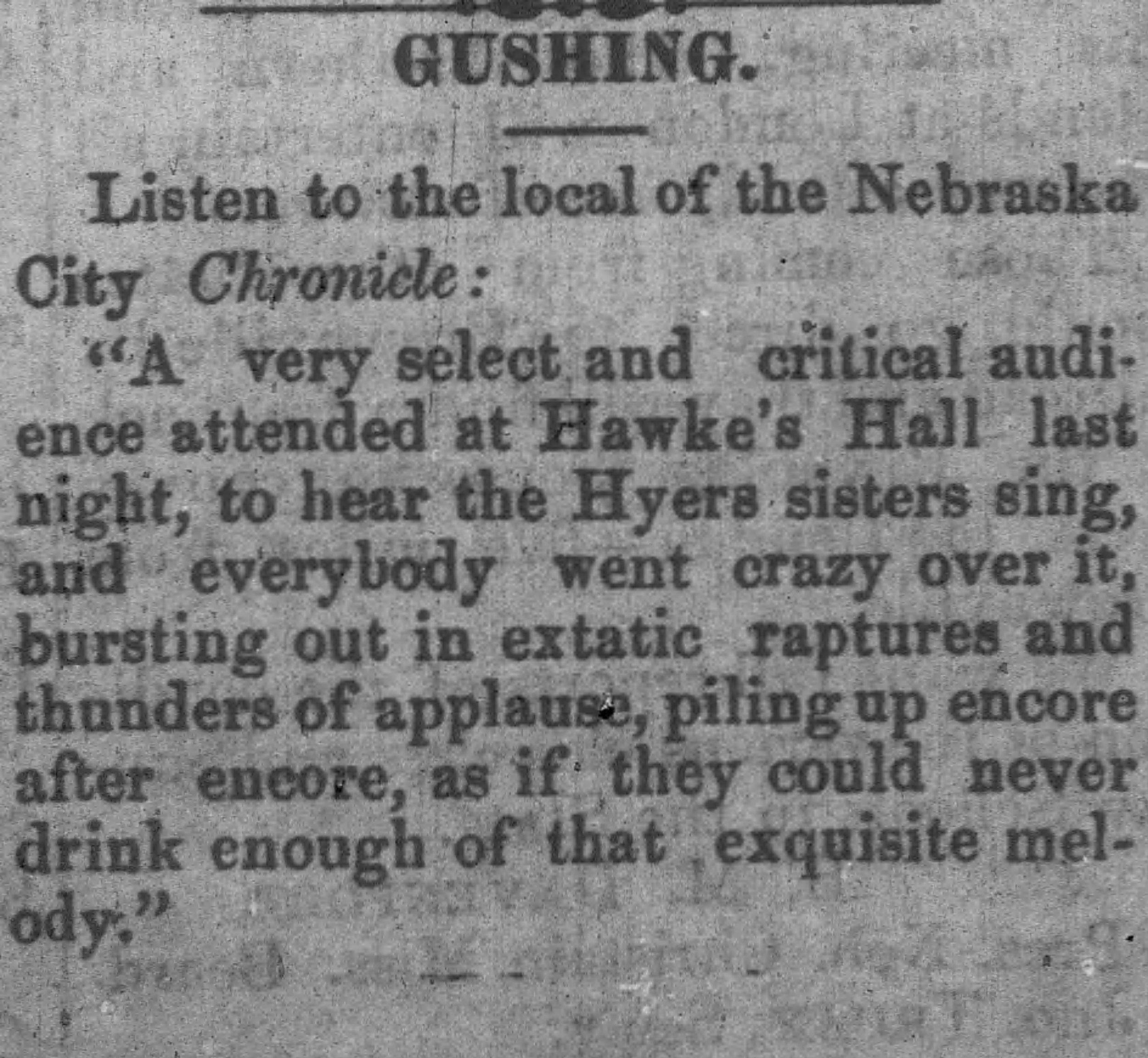

The Beatrice Express, 1871: A “gushing” review from the Hyers Sisters first cross country tour.

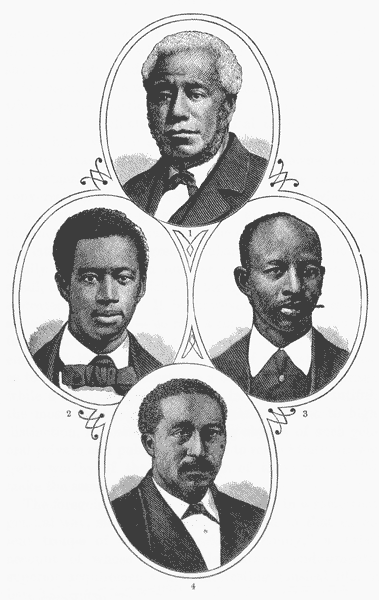

The Luca Family Singers got their start on the abolitionist circuit. Later, John Luca (bottom) joined the Hyers Sisters Combination. Alexander (center right) became a Georgia Minstrel.

Program for Out of Bondage, 1876

Program notes for Out of Bondage, 1876.

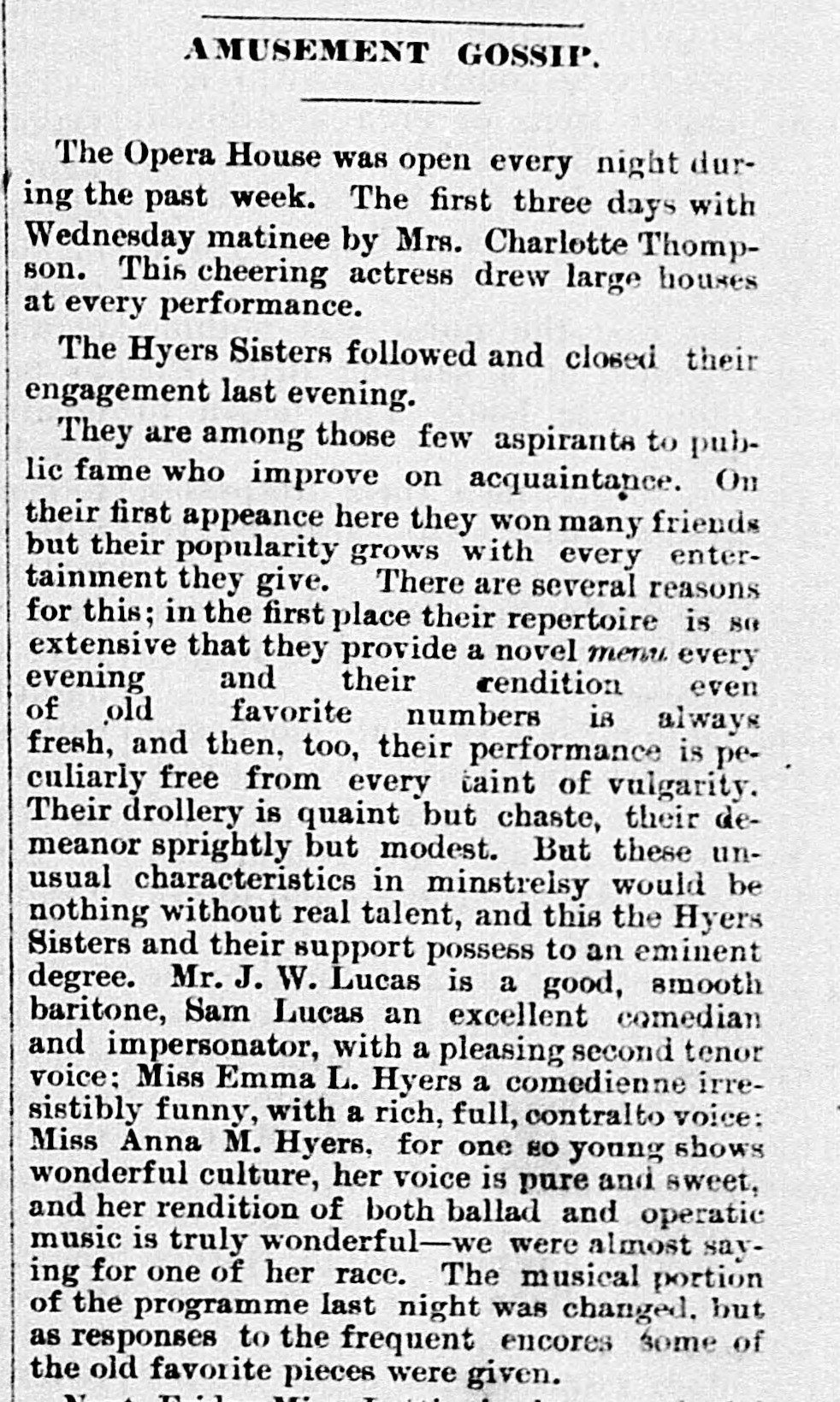

St. Paul Daily Globe, 1878: A favorable review which nonetheless categorizes the program as minstrelsy with “unusual characteristics.”

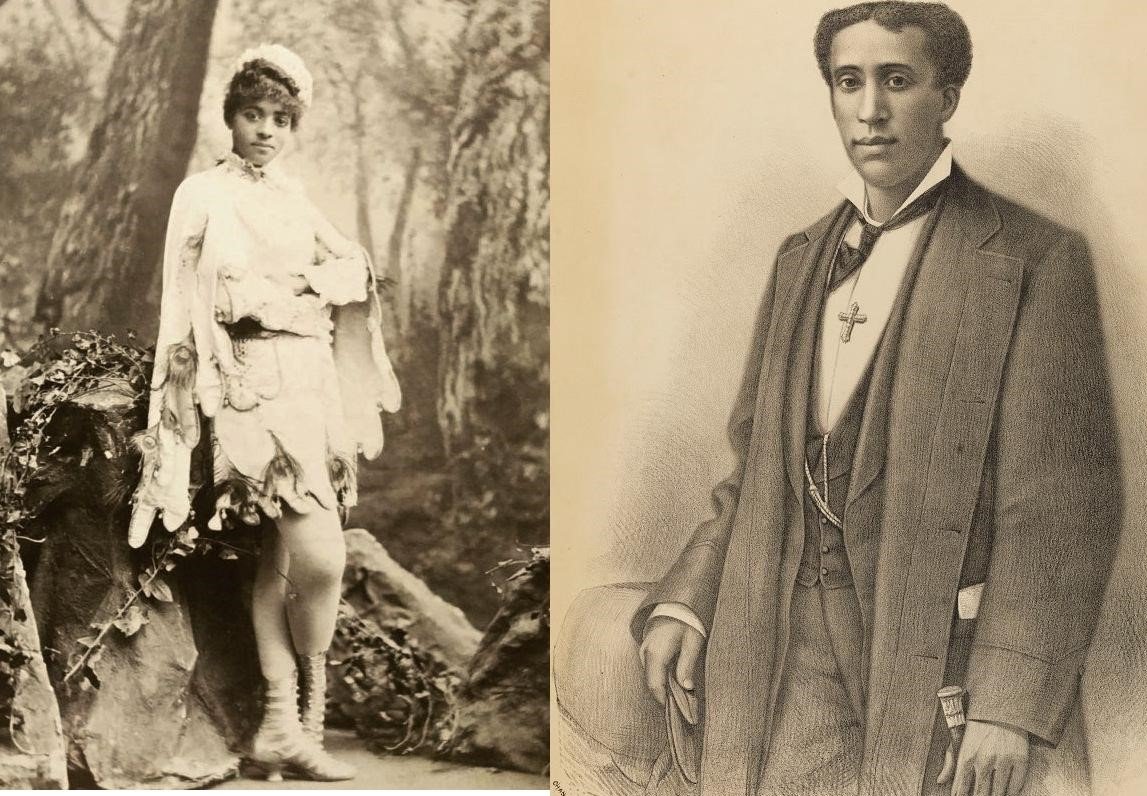

Emma Louise Hyers and Sam Lucas: Rumors of their love affair lingered even after their deaths.

Buchanan County Bulletin (Missouri), 1878: Sam’s abrupt departure from the group sparked speculation across the country.

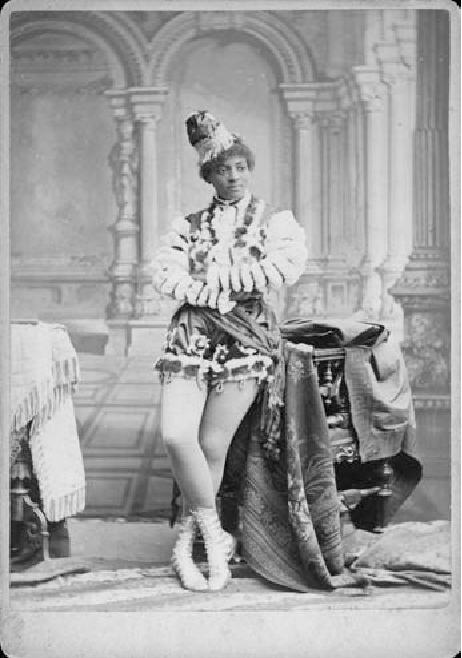

Anna Madah (now Madah A. Hyers) in the title role of Urlina, the African Princess, 1879

Emma Louise (now Louise E. Hyers) as the Prince in Urlina, c. 1879

Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins (date unknown): In 1879, Lucas commissioned Hopkins to write a play for his new company. Then called The Underground Railroad and now known as Peculiar Sam, it is the earliest known production of a play penned by a Black woman.

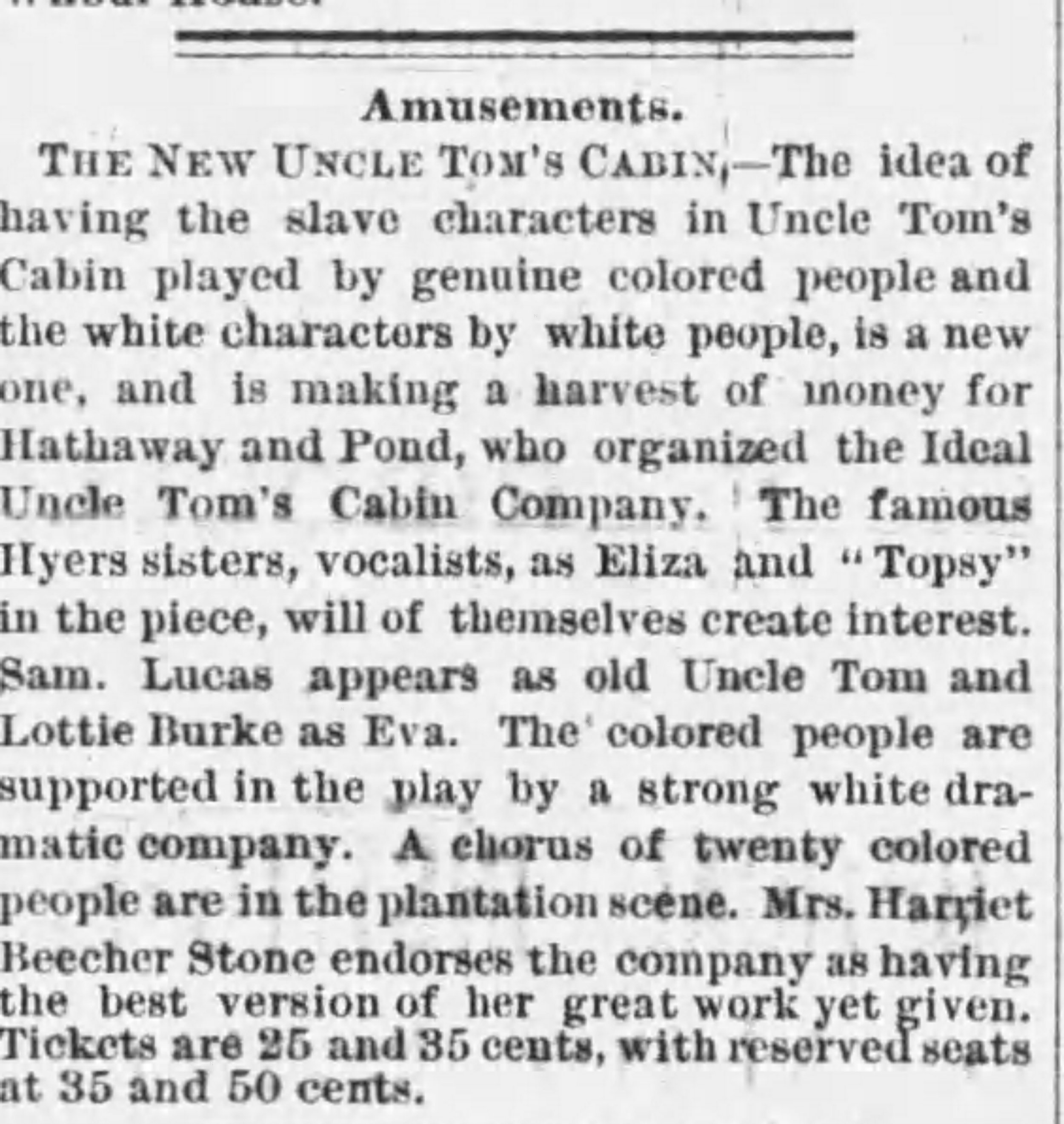

Fall River Daily Evening News, 1880: Lucas and the Hyers sisters briefly reunited for a production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, remarkable for its integrated cast and its stamp of approval from author Harriet Beecher Stowe.

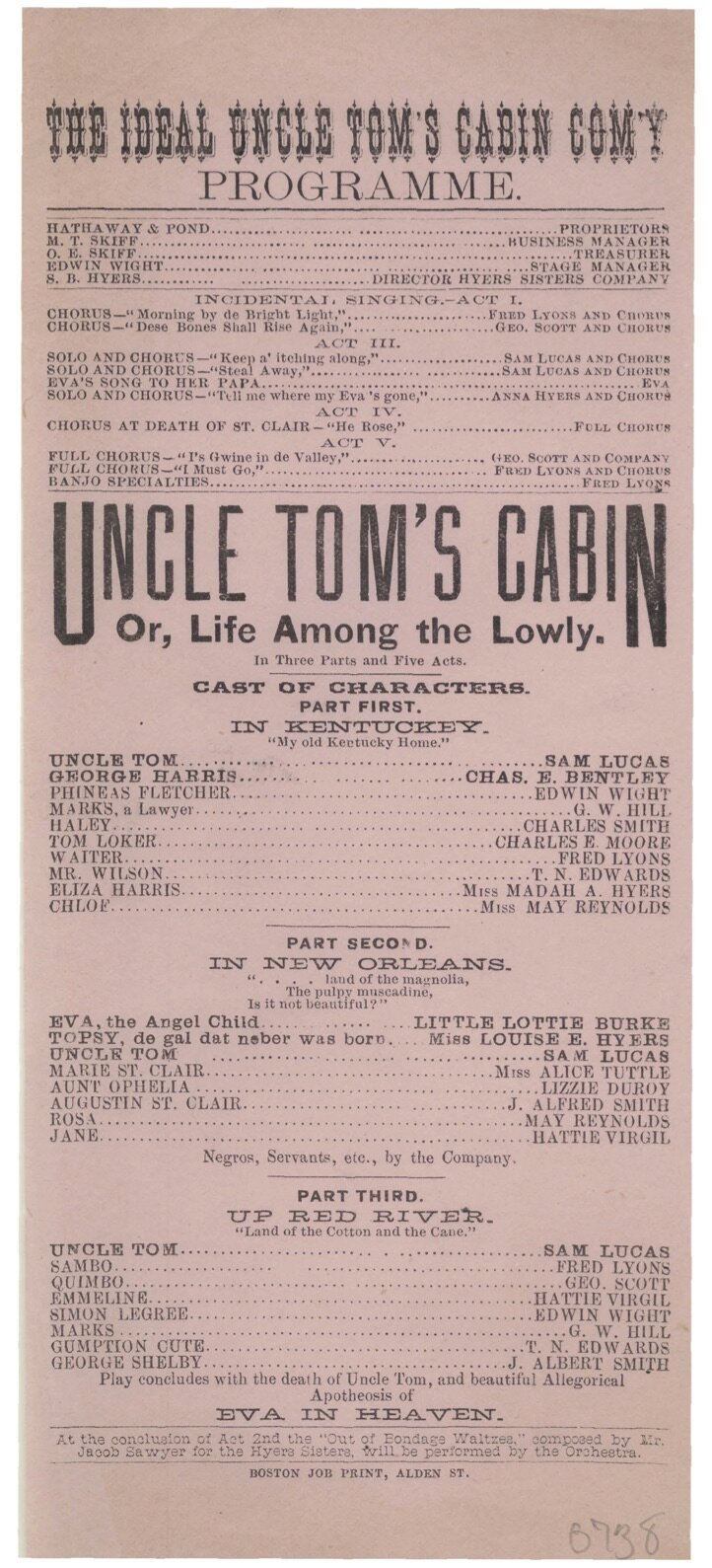

Program for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1880

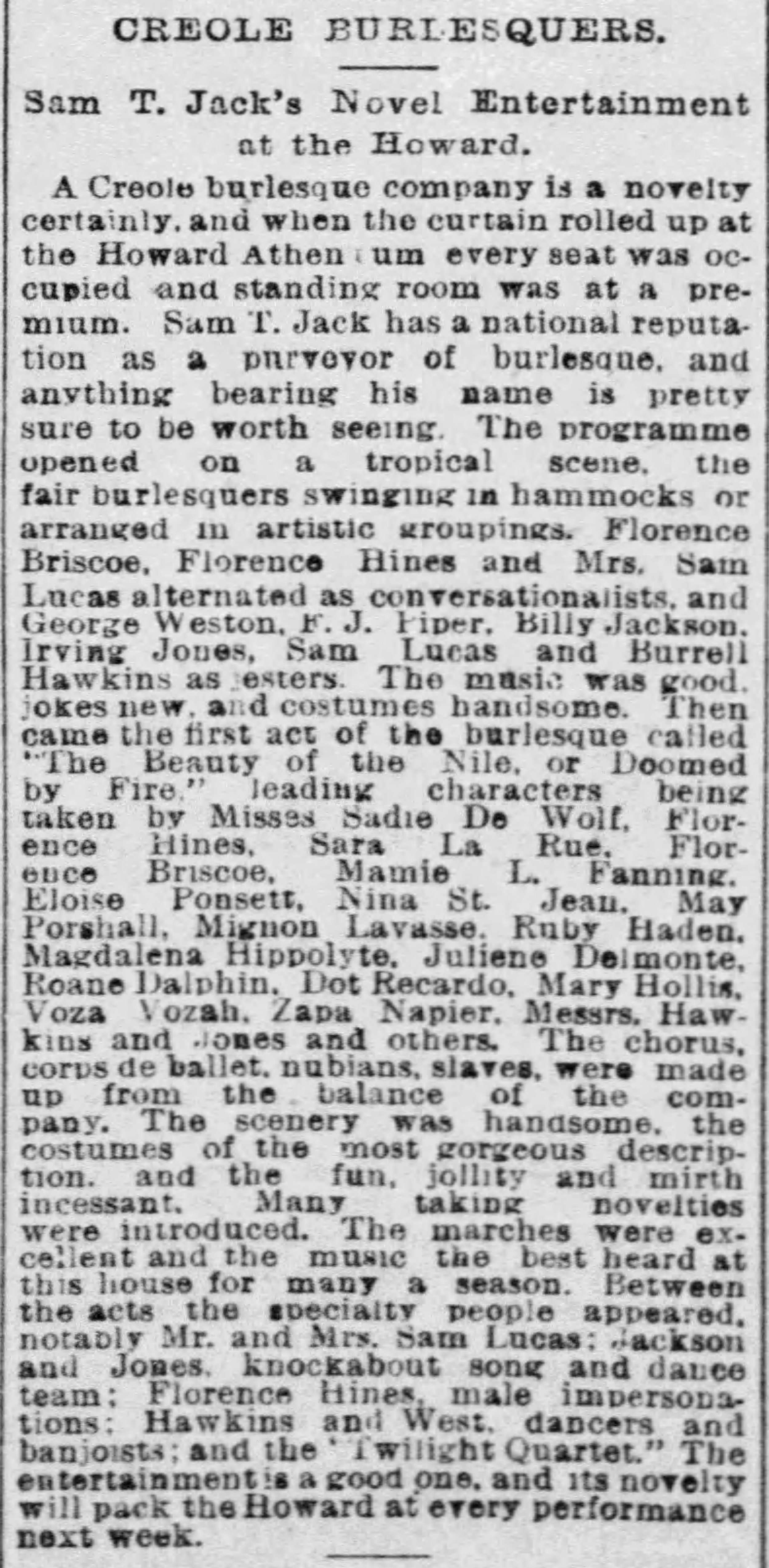

Boston Globe, 1890: A review of The Creole Show - a minstrel structure, with women as interlocutors.

Fall River Daily Globe, 1898. An ad for Sam Isham’s Octoroons, featuring Madah Hyers.

St. Paul Globe, 1897: An ad for the Black Patti Troubadours, headlined by Sissieretta Jones. Black Patti Troubadours was the last performance space for Louise Hyers…

…and the first performance space for Ada Overton. More on her next week!