EPISODE 3

The Frogs

Episode 3: Black Musical Beginnings (1894-1909)

A journey with Bob Cole, J. Rosamond Johnson, Bert Williams and George Walker - visionaries of song and performance, and creators of Black musical theater.

Hosted by: Brittany Bradford

Guests include: Michael Dinwiddie, Rhiannon Giddens

Featuring the voices of: Motell Foster, Lynnette Freeman, Korey Jackson, Toussaint JeanLouis, Steven Anthony Jones, Galen Kane, Lee Aaron Rosen, Keith Randolph Smith

Produced by: CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience

Conceived and Written by: CLASSIX (Brittany Bradford, A.J. Muhammad, Dominique Rider, Arminda Thomas, Awoye Timpo)

Sound Design and Editing: Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube

Associate Sound Engineer: German Martinez

Theme Song: Alphonso Horne

Original Music: Jeffery Miller

+TRANSCRIPT

BRITTANY Hello again friends! Welcome back. This is officially the halfway point of our journey through this exploration, and I’m sure you all have tons of thoughts and ideas to share, and I’m really curious to hear them all. As a reminder, or for those who may be joining us for the first time, this is the CLASSIX podcast, (re)clamation, an intervention in the current conversation around theatre history, where we recenter and uplift the Black writers and storytellers of the American theatre - both the celebrated and the forgotten. My name is Brittany Bradford and this is episode 3 of our series on Black Performance in the Era of Minstrelsy. And this week, we’ll be exploring Black Musical Beginnings.

On a summer evening in 1894, a New York Sun reporter walked up to a rooftop garden and saw a performance by a man billed as “Koo-i-baba”, the Hindu baritone. From the reporter’s perspective the man was not a particularly skilled singer, but he immediately recognized him as the same Colored man he’d seen a few weeks prior in a Philadelphia show. The reporter asked the manager about the charade. The manager explained that “there was such a prejudice” against Black performers that he could never consider hiring a performer named Johnson or Jackson -- billing this Black man as Hindu was the only way to make him palatable to his white audience.

Writing in the Sun, the reporter asks,

VOICE OF NEW YORK SUN REPORTER “What then can be the fate of the aspiring negro singer, reciter, or actor in the face of such prejudice among people who began fighting three-three years ago to set him free and put him upon an equality with the whites of the South?”

The world of 1894 is very different from the world in which we met the Hyers Sisters and Fisk Jubilee Singers in the previous episode. If you remember, in 1871, Charles Hicks’ Georgia Minstrels had toured without blackface; now in 1894, black troupes were corking up to suit the audience demand. In 1880, the Hyers Sisters produced the first truly integrated staging of Uncle Tom’s Cabin; by 1894, a similar venture in San Francisco was doomed by white actors’ refusal to trod the boards with a black Uncle Tom. While the landmark Plessy v. Ferguson case codifying Jim Crow was still two years away, already the promise of Reconstruction has been dismantled and overtaken by a national fervor of white supremacy. Even in the North the movement toward freedom was met with hostility. To be sympathetic to someone’s fight for freedom is not to say that you want them to be equal. This plays out in the arts in the same way it plays out everywhere else.

Even so, Black artists continued to work toward a more just society and strive toward greater opportunity. Their vision would launch a new generation of artists, and their renewed attention to community would create new art forms and a whole new scene. We spoke to NYU professor Michael Dinwiddie about this era.

MICHAEL DINWIDDIE “So you have this kind of African American explosion of “we are free” by, you know, 1865, we were an illiterate people. By 1900, most of us can read, you know, in one generation, we've gone through that. In one generation, we're owning land, we're having property, we're doing all these things we really have, despite the backlash that's happening, because the-- as we know, from Obama, the more you advance, the more you’re gonna have to deal with what comes after. And so in the 1890s, you have a period where these African American men who have grown up seeing and seeing minstrelsy, some of them performing in minstrelsy, now have the opportunity to create their own shows.”

BRITTANY No two groups exemplify this transformation more than two duos: Cole and Johnson and Williams and Walker.

Now, I’m not trying to play favorites here, I love a lot of these folks, but you all know from the previous episode that my heart goes slightly a flutter for Bob Cole. Part of that is my fascination with his ability to change. I had a teacher once who said that the way to stay in this business is to be Darwinan in nature, to be adaptable.. Ava Duvernay talks about being a shapeshifter and doing many things because “You can’t hit a moving target.” And I have a lot of curiosity about how one does that and stays true to themselves. And how one does that as a Black artist in the 19th century. And also, just as a consumer of art...I just wish I could see his skills at work. Because he, like many of the folks we’ve met thus far, sounded like an absolutely incredible, engaging, complex artist.

As James Weldon Johnson once said, Bob Cole was -

VOICE OF JAMES WELDON JOHNSON “...the greatest single force in Negro theatre. Most facile, good singer, excellent dancer, could write dialogue and music, stage the play, act the part, and was a serious student of the theatre and drama.”

BRITTANY So let’s get into it. My buddy Bob Cole was born in Athens, GA in 1868, the only boy born to parents heavily involved with the Negro Reconstruction politics of the time. Cole was highly educated: He was a student at one of the Freeman schools, which were founded when he was born, and then went on to study at Atlanta University. Not only was Cole’s upbringing heavily influenced by the Black political movement of the time, but his family was also quite musical. He grew up with a piano in the home, having music playing constantly. This blending of music and politics, the idea of artist as citizen, would end up being a character trait of much of Cole’s later works.

When he set off on his own in 1891, he got his first big break when he jumped on board the Sam Lucas vehicle, The Creole Show, which we mentioned in Episode 2. Perhaps it was serendipitous that his first break would come working on a show with Sam Lucas, a man who worked his way up the ladder when he was starting himself, as Bob Cole ends up doing the same in The Creole Show. He initially came in with his comedy-dancing partner, and was a songwriter for the revue. He then became the stage manager of the show, then wrote skits for the show, and then songs for the show, publishing his first two songs in 1893.

In 1894, during an off-season for The Creole Show, Cole heads to New York and forms a stock company at Worth’s museum. Worth’s was what was known as a dime museum that would have entertainments and performances as well. It was popular, cheaper entertainment for the working class, hence the dime in dime museum. In his unpublished autobiography, composer Will Marion Cook recalled:

VOICE OF WILL MARION COOK "Worth’s Museum, on Thirtieth Street and Sixth Avenue, was the place where I first got any real experience in Negro show business. On this corner was a small theater where the best performers—Ben Hunn, Tom Brown and Bob Cole—often put on afterpieces and shared in the proceeds with the proprietor. I lived on Thirty-second Street near there. When Bob Cole told me he was to run the show for a week and asked me to be musical director, I jumped at the chance."

BRITTANY Perhaps because of how important education was within Cole’s own household and a sign of his inventiveness and ingenuity, the stock company becomes a training school. It is the first of its kind: a Black training ground led by other black performers. The training is a pipeline to the stock company itself, something that continues to happen to a smaller degree, in training programs across the country to this day- students at UC San Diego working at La Jolla Playhouse, or Yale Drama students connected to Yale Rep, and so on. The school lasts for about 2 years, ending just as Cole’s time in the Creole Show also comes to an end.

Cole’s next venture proves to be as meaningful and as serendipitous as the first. Similar to Charles Hicks, Cole is able to create opportunities for himself wherever he goes. But perhaps unlike Hicks who was his own one man band through and through, Cole’s career trajectory was really remarkable because of the collaborations he formed. For the 1896-1897 season, Cole jumps into yet another successful tour, this time with Black Patti’s Troubadours. Black Pattis’ Troubadours, if you remember, was a white-owned troupe named for and headlined by Sissieretta Jones, who, like the Hyers Sisters, began as an opera singer, and when Cole enters the company, his time there intersects with that of two other up-and-coming minstrel stars, one who becomes a legend in her own right: Aida Overton Walker, and the other who would be an influential collaborator with Cole: Billy Johnson. The two hit it off immediately. in their one season together with the Troubadours, they began to write.

And as this is happening, Cole attempts to use his new status in the company to advocate for the entire group. He fights for higher wages and better working conditions. When the managers balk he takes his sheet music and heads out of town, leaving the troupe material-less. The white company owners retaliate and have Cole arrested. When the case goes to court. Cole argues:

VOICE OF BOB COLE “These men have amassed a fortune from the product of my brain, and now they call me a thief; I won’t give up!”

BRITTANY But he loses and is sentenced to jail. On top of that, he is blacklisted by the management of Black Patti’s which prevents him from performing on stage in the United States. In addition, the company owner threatens to boycott for life any performer who appeared in one of his productions. Not to be outdone, Cole refuses to bend. In an 1898 response to the blacklist he wrote the “Colored Actor’s Declaration of Independence” asserting the need for Black ownership of companies, projects and managers. And just like Hicks, Cole finds a workaround.

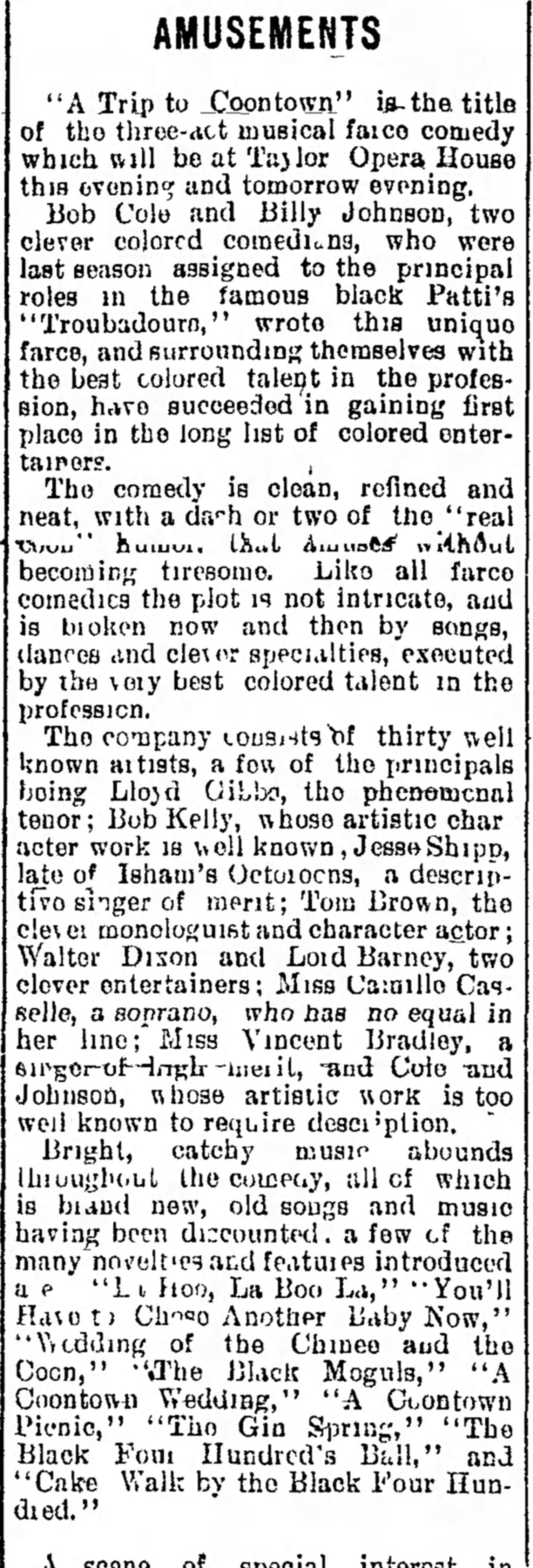

Within a year, Cole and Johnson are working on a new show, A Trip to Coontown. What a title. The show follows Johnson’s Jim FlimFlammer, a con artist, who unsuccessfully tries to trick an old man (played by Sam Lucas) out of his pension. Bob Cole appears as Willie Wayside, a slow-witted “Jim Crow”-like tramp only played in whiteface, who manages to save the day, an example of how Cole was working to switch up character tropes from minstrelsy.

Unable to find venues in the United States, Cole and Johnson take the show to Canada where it is so popular that in 1898, New York producers Klaw and Erlanger break with their white brethren and open the show at Jacob’s Third Avenue Theater.

A Trip to Coontown was a defining moment in Black theater history. It was the first truly all-Black production - the first to feature a Black cast and Black writing and production and management team. [As Issa Rae would say, “Everybody Black!”]

With a renewed determination to transform the theatrical landscape Bob Cole refused any performance of the show in a segregated theater.

That said - Let’s take a minute and talk about that title. And in order to talk about that title we’ve got to have a chat about what was known as “the coon song.”

In her book Ragged but Right, Lynn Abbott outlines the evolution of the songs.

“Coon songs,” she says, “with their ugly name, typically featured lyrics in Negro dialect, caricaturing African American life, set to the melodious strains of ragtime music… The designation first took hold during the 1880s, under the influence of such portentous hits as “The Alabama Coon,” “I’m the Father of a Little Black Coon,” and “New Coon in Town,” but the real “craze” commenced in 1897 with the inception of the “ragtime coon song.” As ragtime reached the height of its popularity, the mainstream public was becoming some- what obsessed with Black vernacular music, dance, and poetics. This condition produced an exponen- tial increase in professional opportunities for black entertainers and encouraged African Americans in every branch of the profession to explore their distinctive musical folklore more forthrightly. However, African Americans gained the mainstream stage only because white audiences demanded they be there. Their fortunes remained subject to the coon song–loving disposition of the dominant race and the inherited conventions of minstrelsy.”

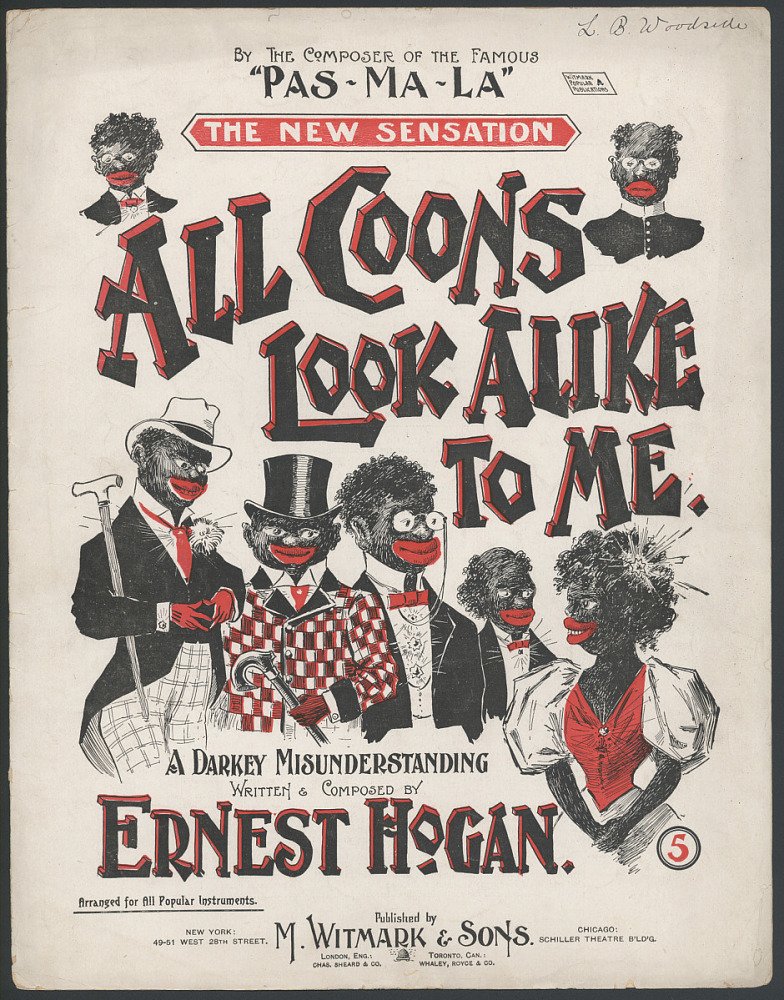

And no song better exemplifies this than Ernest Hogan’s 1896 hit “All Coons Look Alike To Me”.

Ernest Hogan was a widely-respected Black performer in the late 19th century. He was a very popular entertainer, and a pioneer in Black musical shows. He is credited with composing the first ragtime song, “La Pas Ma Las” in 1895. It did well, but nowhere near the song he released the following year.

The lyrics were a spoof of the song “All Pimps Look Alike to Me.” The song was an enormous hit. But the title inspired a great backlash. Hogan later deeply regretted ever writing the song. Both the title and the subsequent lyric sheet cover art inspired a great ugliness from which he would never mentally recover. Here’s Rhiannon Giddens on the subject -

RHIANNON GIDDENS You kind of have to get, like, look at enough of these music sheets, you know, to look at enough of these grinnin’-- I mean, it's tough. It's really really tough. There’s always a moment in my show, when I talk about the Coon song, you know, which is just not great. I mean, it's just minstrelsy. 2.0, right? It's, it's, it's using all the same stuff. And we consider like, you know, Black minstrels got really, really rich off of some of these songs as well, you know, and that just adds to the complexity of it. But I talked about All Coons Look Alike to Me. Such a cultural flashpoint. And I tell people-- I'm like, these were the popular songs. Y'all got to understand, like this song with this title. I said, there's always a [gasp] you know, like, “That's terrible” and I'm like, “Yes. And that man made a lot of money. That Black man made a lot of money off of that song.” Did he regret it? He said he did. But what is--you know, like, just adds all this stuff. But then you get like getting in a knife fight if you whistled, the first few bars of that tune, you know? So then I look at that song. And I'm like, it's a catchy song. And that's what like, we haven't even talked about why was minstrelsy so popular? Why was it? Why did it take over?”

BRITTANY By 1909, ten years after the premiere of A Trip to Coontown, Bob Cole did an interview with the Indianapolis Freeman that revealed his own transformation:

VOICE OF BOB COLE “The word “coon” is very insinuating and must soon be eliminated... I am going to crusade against the word “coon”... the best class of white people in America abhor the word “coon” and feel ashamed whenever they hear it used.”

BRITTANY It is interesting to say the least that it was quote “the best class of white people” that Cole seems to have the most concern for on this topic...And when the interviewer asked how he had come to name his comedy of several years back “A Trip to Coontown,” he replied -

VOICE OF BOB COLE “That day has passed with the softly flowing tide of revelations.”

BRITTANY It is important to note that Bob Cole was a forward thinking artist who himself never performed in blackface. Over the next decade, Cole and other Black artists who had gained success by trading in on the popularity of the coon song would come together and think about their work, their impact and create a new vision. They would gather and build a new sense of fellowship. They were building a new Black artist community and as a community they began to realize they could no longer make work in the same way. It’s eerily reminiscent to conversations had in the Black artist community in 2020 as well. These artists of the past, they start to move away from the tropes of the early minstrelsy period. They branch out and discover new ways of telling stories. In other words, they would begin to evolve.

But that was later. In 1898, A Trip to Coontown would continue to find success as it embarked on what became a 3-year tour. The end of that tour was the end of Cole and Johnson - Billy Johnson, anyway. Shortly after the pair parted ways, Cole became acquainted with two musical brothers from Jacksonville, Florida, also named Johnson: J. Rosamond and James Weldon.

Meanwhile…another duo, from the West Coast, was making its own mark. And we’ve finally arrived at someone you might know.

RHIANNON GIDDENS I'm, of course really super interested in Williams and Walker because they were such interesting examples of two different styles, you know, of taking those themes of minstrelsy. Bert Williams, obviously being comfortable in blackface and all the different levels, even the different layers of him being with Bahamian and not even considering himself American in some ways, and you know, using mask work in comparison to, you know, white folk using mask work, like you talked, thinking about working class people say connecting to this old sort of European tradition, you know, of, of using that to tell the story of the working class there's elements of that in minstrelsy, and to see how he uses, you know, how he uses that mask work in similar and yet not similar ways to, you know, other black minstrels. And then, of course, his partner who did not use blackface. So they kind of represent to me a lot all at once. Bert Williams is an obvious one, but he's, you know, really fascinating to me. And we also have some of the, we also have some of their recordings, you know, not a lot, but you know, that's huge. So that tends to also kind of dominate, like, who you can really study, if, if there's no recordings of somebody, you kind of hit a, you hit a wall, which is, you know, the way it is.

BRITTANY Born in the Bahamas, Bert Williams emigrated with his family to the US as a child, eventually settling in Riverside, Ca (not far from where I spent my childhood…). In 1891, he was persuaded by veteran minstrel impresario Lew Johnson (remember him?) to join his troupe for a season.

VOICE OF BOOKER T. WASHINGTON “One day a colored man named Lew Johnson, who kept a barber shop in San Francisco, asked Bert Williams if he did not want to join a little company that he intended to take up along the coast to play the lumber camps, between San Francisco and Eureka, and then come back by way of the mining camps at the western edge of the mountains. That was the way Bert Williams gained his entrance to the stage.”

BRITTANY That was Booker T. Washington. While Bert Williams fell into entertainment, George Walker had been actively pursuing it since he was a child. And after cutting his teeth in local minstrel shows, he set out from Lawrence, Kansas to California to hone his craft.

VOICE OF GEORGE WALKER “The West was not so up-to-date as it is now...I had to rough it, and rough it I did. There were many quack doctors doing business in the West. They traveled from one town to another in wagons, and gave shows in order to get large crowds of people together, so as to sell medicine...I did not hesitate to ask the quacks for a job. First one and then the other hired me. When we arrived in a town and our show started I was generally the first to attract attention. I would mount the wagon and commence to sing and dance, make faces, and tell stories, and rattle the bones...

BRITTANY Eventually Walker found himself in San Francisco in 1893, and in Bert Williams he found a kindred spirit. The two teamed up, honing their craft - and their act.

VOICE OF GEORGE WALKER “In those days, black-faced white comedians were numerous and very popular. They billed themselves “coons.” Bert and I watched the white “coons,” and were often much amused at seeing white men with black cork on their faces trying to imitate black folks. Nothing about these white men’s actions was natural, and therefore nothing was as interesting as if black performers had been dancing and singing their own songs in their own way...we thought that as there seemed to be a great demand for black faces on the stage, we would do all we could to get what we felt belonged to us by the laws of nature...as white men with black faces were billing themselves “coon,” Williams and Walker would do well to bill themselves the “Two Real Coons,” and so we did...

BRITTANY The characters were based off minstrel stereotypes like Zip Coon and Jim Crow. In the duo, Walker at first played the slower character while Williams played the sly huckster, but it didn’t work out as well, and they discovered flipping the roles served both men better. And Bert made another discovery.

VOICE OF BERT WILLIAMS “...one day at Moore’s Wonderland in Detroit, just for a lark I blacked my face and tried the song, “Oh, I don’t know, you’re not so warm.” Nobody was more surprised than I when it went like a house on fire. Then I began to find myself.”

BRITTANY Williams was from Nassau in the Bahamas. He was light-skinned and didn’t really think of himself as American as he was West Indian. He spent a lot of time studying Southern Black American dialect and he felt putting on the mask of blackness helped him get into the role. Walker on the other hand, who had grown up with minstrel troupes in the South and was darker than Williams, really didn’t like blackface, and did not put cork on. Two completely different approaches to Black performance, and within the same duo.

VOICE OF GEORGE WALKER “Black-faced white comedians used to make themselves look as ridiculous as they could when portraying a “darky” character. In their “make-up” they always had tremendously big red lips, and their costumes were frightfully exaggerated. The one fatal result of this to the colored performers was that they imitated the white performers in their make-up as “darkies.” Nothing seemed more absurd than to see a colored man making himself look ridiculous in order to portray himself. My partner, Mr. Williams, is the first man that I know of our race to attempt to delineate a “darky” in a perfectly natural way, and I think much of his success is due to that fact.”

BRITTANY In 1896, Williams and Walker’s “Two Real Coons” act landed them a New York gig in a vaudeville show called the Gold Bug. That show died quickly, but the pair made such an impression that they immediately got booked at Koster and Bial’s, a prominent 3700-seat music hall, where they played for 40 weeks. They were personally responsible for making the Cake Walk a New York (and then national) obsession.

Even before they came down from their first brush with fame, Walker and Williams sensed that they could do more, and do better.

VOICE OF GEORGE WALKER “As the “Two Real Coons” we made our first hit in New York…before our run terminated we discovered an important fact, viz: the one hope of the colored performer must be in making a radical departure from the old “darky” style of singing and dancing. So we set ourselves the task of thinking along new lines.

The first move was to hire a flat in Fifty-third street, furnish it, and throw our doors open to all colored men who possessed theatrical and musical ability and ambition. The Williams and Walker flat soon became the headquarters of all artistic young men of our race who were stage-struck. Among those who frequented our home were: Messrs. Will Marion Cook, Harry T. Burleigh, Bob Cole and Billy Johnson, J.A. Shipp, the late Will Accoo, a man of much musical ability, and many others whose names are well known in the professional world. We also entertained the late Paul Lawrence Dunbar, the negro poet, who wrote lyrics for us. By having these men around us we had an opportunity to study the musical and theatrical ability of the most talented members of our race. At that stage of the development of Williams and Walker, we saw that the colored performer would have to get away from the ragtime limitations of the “darky,” and we decided to make a break, so as to save ourselves and others.”

BRITTANY From these salons, Williams and Walker began to find their all-star crew and they were soon collaborating with composer Will Marion Cook and famous poet Paul Laurence Dunbar who sometimes assumed the role of lyricist. The Williams and Walker Company was also enhanced by two talented women who would become iconic in their own right; one of whom we’ve already mentioned - the brilliant dancer, choreographer, and actress, Ada Overton - who would soon marry George Walker and become Aida Overton Walker; and young singer and actress Abbie Mitchell. With this team, Williams and Walker began creating the plays that would cement their reputations, in particular one which has come to define the era - their 1903 musical, In Dahomey, which we will take a closer look at in Episode 5.

This new creative community would transform the landscape beyond Williams and Walker.

MICHAEL DINWIDDIE “In the 1890s, you have a period where these African American men who have grown up seeing and seeing minstrelsy, some of them performing in minstrelsy, now have the opportunity to create their own shows. And they have the opportunity to produce them, direct them, tour them around the world, et cetera, et cetera cetera because remember, Broadway doesn't come into being until 1904. Really, that's when Times Square happens and all that. So this notion of “it has to be on Broadway to be a hit” is not really, you know, thought of in that way. So but you do find African American shows going to Broadway. I'm going to talk about the Johnson brothers, you know, James Weldon Johnson and Jay Rosamond Johnson, James Weldon Johnson wrote, Lift Every Voice and Sing, which became the Negro national anthem. But you know, they first made their money in the Broadway world, writing music for white entertainers, writing songs that became hit songs for them. But then they started putting it in their own shows, and what I love about their shows, so I'm going to just talk about two of their shows. Because, I mean, it's so fascinating. I'm going to talk about the Red Moon, which is a story, a love story of a Native American Girl and African American man who fall in love. And there's resistance from their two families, of course, but they end up getting together and being together and everything. So already you see African Americans thinking, first of all, it's part of our tradition, we've always been connected with other groups. We've always been, if you look at all our skin colors, we’re everything, right? You know, everything. So that's the play they’re writing, kind of exposing the audience to the truth of the fact that in our acculturation, interracial love is not an alien concept. Okay, that's number one. So like, that's already a revolutionary step. Then the other one that I want to mention is the Shoo Fly Regimen, in which we have a heroic African American lead, which remember now this is all contradicting minstrelsy, who is going to go off to fight in the Spanish American War. He's a student, a college student, a college, this period when, you know, so few people have gone to college, he goes out and his girlfriend or fiance, I should say, is against it. But he comes back and he's a hero. So those are two shows that hit me. And then of course, the other thing that hit you about that period is African Americans are proud of their Africanness.”

BRITTANY You know, I’ve talked a little about my love and respect for Bob Cole. And I will say, there are a lot of people I’ve grown to admire throughout this, but why I think I gravitate toward Bob- I think we’re on a first name basis now- is because of the deep feeling of soul understanding soul that I have felt whilst learning about his life. And of course, I don’t know him, he didn’t know me, who knows if he’d feel the same way about me, right? This could be purely ego speaking. But it feels in my body like a sense of relation. I can only speak on my own experiences and say: I have felt dualities at play to being a Black artist in this country. There are compromises, there are challenges, and there are moments of community and creativity and construction of a new and better future. I think the challenge is to not compromise so much that you lose your essence. Your humanity. The reason you’re doing this in the first place. And how to do that in the moment is sometimes very hard. For me, I’ve found that it’s through making some mistakes or finding myself involved in not-as-inclusive collaborations that I’ve learned what it is I will and will not accept in the future. And holding tightly to the community around me who also believes in, and is putting the work into building the future we want to see. And I get a sense of that from Bob Cole. And I admire that. I’m learning from that. And I guess I think that maybe, in the way that I feel if I met James Baldwin that we would hopefully be friends and have meaningful conversations about becoming better artists, better citizens, better humans, I suppose, in what I know of Bob Cole, I feel like I can see myself having long conversations in the lobby after one of his shows, drinking cheap beer and eating cheese plates, talking about - ok, now what next? What have I learned? How can we make this better? And it’s those conversations and sense of community that keeps me in this just as much, if not more than the work itself. For me, the process is just as important as the product. And that process should be generative. It has energy, it moves us to act and to not stay stagnant. I feel that energy now predominantly when I’m in Black spaces, and it’s why, frankly, they’re some of my favorite places to create art in. Black spaces, women-led spaces, intersectional spaces. And I love that it’s not a new concept, as Michael Dinwiddie said earlier. That we get to share that energy and be in conversation now, with those folks who were creating a new world then.

This growing arts community that they were producing really takes off between A Trip to Coontown and later Bob Cole vehicles like Red Moon and Shoofly. Their imagination gets bigger, their vision becomes more vast, and they begin to accomplish those things that were mere ideas for who knows how long in their artistic processes.

But of course, whenever you have a period of Black Excellence, we know what happens next. In New York, the Backlash of 1900 arrived on two fronts. The first was a riot. James Weldon Johnson recalls:

VOICE OF JAMES WELDON JOHNSON “Early in the evening of August 15 the fourth great New York race riot burst in full fury. A mob of several thousands raged up and down Eighth Avenue and through the side streets from Twenty-seventh to Forty-second. Negroes were seized wherever they were found, and brutally beaten. Men and women were dragged from street-cars and assaulted. When Negroes ran to policemen for protection, even begging to be locked up for safety, they were thrown back to the mob. The police themselves beat many Negroes as cruelly as did the mob. An intimate friend of mine was one of those who ran to the police for protection; he received such a clubbing at their hands that he had to be taken to the hospital to have his scalp stitched in several places. It was a beating from which he never fully recovered. During the height of the riot the cry went out to ‘get Ernest Hogan and Williams and Walker and Cole and Johnson.’ These seemed to be the only individual names the crowd was familiar with. Ernest Hogan was at the time playing at the New York Winter Garden, in Times Square; for safety he was kept in the theatre all night. George Walker had a narrow escape. The riot of 1900 was a brutish orgy, which, if it was not incited by the police, was, to say the least, abetted by them.”

BRITTANY The second was...a union. In 1900, The White Rats of America was born. The group’s mission was to advocate for the rights of vaudeville performers. There was a catch though - membership was limited to white men, and the Rats fought viciously to keep top dollar jobs out of Black hands. I think it’s important to note here that one of the members of White Rats went on to found Actors’ Equity. But instead of deterring the Black artist community, this opposition only served to galvanize them. From the rubble of the riots, they built a whole new foundation.

VOICE OF JAMES WELDON JOHNSON “...by 1900 there was a new centre established in W 53rd St. In this new centre there sprang up a new phase of life among coloured New Yorkers. Two well-appointed hotels, the Marshall and the Maceo, run by coloured men, were opened...and became the centres of a fashionable sort of life that hitherto had not existed...the Marshall, run by Jimmie Marshall, became famous as the headquarters of Negro talent. There gathered the actors, the musicians, the composers, the writers, and the better-paid vaudevillians; and there one went to get a close-up of Cole and Johnson, Williams and Walker, Ernest Hogan, Will Marion Cook, Jim Europe, Ada Overton, Abbie Mitchell, Al Johns, Theodore Drury, Wil Dixon, and Ford Dabney.”

BRITTANY They moved from inside their own apartments and flats and spilled into public spaces, creating a dizzying Black performance scene with the brightest talents of the era. Banned from the White Rats, The Players and the Lambs, they banded together to create their own organizations. 1908 saw the birth of The Frogs, the brainchild of George Walker. Founding members included Bert Williams, Bob Cole, J. Rosamond Johnson, writers Jesse A. Shipp and Alex Rogers, New York Age arts critic (and lyricist) Lester Walton, and trailblazing musician James Reese Europe. This visionary organization was created to connect Black theater makers to Black artists and thinkers in art, literature, music, scientific and liberal professions, and patrons of the arts. The group was designed to create quote “a library relating especially to the history of the Negro...and the collection and preservation of all folk-lore, of pictures, and bills of the plays in which the Negro has participated.”

This group was a Black arts collective - a coalition built to support each other financially and to establish a legacy. It claimed a space for theatre as worthy of critique and conversation among the other arts.

And soon, other groups started to emerge. The following year, performer Leon Williams created a union of sorts, the Colored Vaudeville Benefit Association, which also served as a relief fund to support older actors and cover burial expenses.

MICHAEL DINWIDDIE Well, first of all, the Rats, the White Rats would not allow blacks. That's, you know, the, that was the white organization of actors and artists. And so the best, and the top African American performers who at the time were really at the top of their game, create something called the Frogs. And, you know, they go before a judge, and he says, I'm not gonna let you name a club, the Frogs, you know, they say, Well, no, this is after Aristophanes the Frogs. That's why we're calling it that. And they're the White Rat. So why not the Frogs I mean, because, because we've always we know, the law is always used against us, and not to benefit us. So but they, they create this club, and, I mean, James Reese Europe is one of the members - and it's really a club with the idea of, we're going to help advance our people as entertainers, I mean, so this is also the time where you have James Reese Europe, one of the great conductors, band leaders, composers of our time, doing concerts at Carnegie Hall. So that to raise music, to raise money for the Colored Music Settlement house in Harlem.

BRITTANY And it didn’t stop there! Black artists continued to build a new infrastructure. Around the country, new theatre venues emerged that were owned or managed by Blacks including the Maceo Theater in Washington, D.C; the Luna Park Theater in Atlanta; the Two Johns Theatre in Indianapolis, and the legendary Pekin Theatre in Chicago. Black publications like the Indianapolis Freeman and The Colored American created a national audience for the promotion and critique of Black shows.

Remember the question from the Sun reporter in 1894?

VOICE OF NEW YORK SUN REPORTER What then can be the fate of the aspiring negro singer, reciter, or actor in the face of such prejudice among people who began fighting three-three years ago to set him free and put him upon an equality with the whites of the South?

BRITTANY Within a decade the answers would sound something like this:

Bob Cole -

VOICE OF BOB COLE “We are going to have our own shows. We are going to write them ourselves, we are going to have our own stage managers, our own orchestra leader and our own manager out front to count up. No divided houses- our race must be seated from the boxes back.”

BRITTANY George Walker -

VOICE OF GEORGE WALKER “There is an artistic side to the black race, and if it could be properly developed on the stage, I believe the theatre-going public would profit much by it. The love, the humor, and the pathos of the black race in this country afford a field for wide study, and I am sure the stage is the place where the character of the African race can be studied from a real artistic point of view, with special advantages to all lovers of music and theatrical art.”

BRITTANY Aida Overton Walker -

VOICE OF AIDA OVERTON WALKER “Of course, it takes time to do anything worth while, and especially to carry out great aims and accomplish good work, but when something has been accomplished we consider the time well spent, and so we must go on working in our professions with the hope that the future will bring us more encouragement and better success and less criticism; not that we cannot stand criticism, for we can; but for the reason that our work is a great work and ought to be encouraged in these days when it needs help and encouragement. Our Stage work is grand and our lives can be made beautiful…”

BRITTANY The promise of a new generation was being fulfilled. But in another ten years it would all be done.

Next week we’ll look at the end of the beginning and consider the legacy of this era, closing it out, and seeing what came next.

Thank you as always for going on this journey with us. Special Thank yous to the man, the myth, the legend Professor Michael Dinwiddie who we’re all now obsessed with, and the legendary incredible musician that is Rhiannon Giddens. Make sure to also check out her podcast Aria Code, that “pulls back the curtain on some of the most famous arias in opera.” And thank you to all our actor friends who have given voice to this episode, we love you all immensely.

For more on these infamous duos, check out our website, theclassix.org, and be sure to follow us on Twitter and Instagram @itstheclassix. This episode was produced by CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience. Our sound engineer is Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube. The theme song was composed by Alphonso Horne. The episode music was composed by Jeffery Miller. See you next week!

GUEST BIOS:

Michael Dinwiddie

Michael Dinwiddie is an award-winning playwright/composer and associate professor of dramatic writing at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study, New York University. He is editor of the upcoming Theatre Communications Group (TCG) publication On Holy Ground: An Anthology of Plays and Monologues from the National Black Theatre Festival. A dramatist whose works have been produced in New York, regional, and educational theater, Michael has served on the boards of New Federal Theatre, the Classical Theatre of Harlem, the Duke Ellington Center for the Arts, and the Black Theatre Network, among others. He is a contributing editor of Black Masks Magazine, and a member of the Dramatists Guild and the Television Academy. Select honors include a National Endowment for the Arts Playwriting Fellowship, the FAMU Theatre Medal, a Walt Disney Writers Fellowship at Touchstone Pictures, the NYU Distinguished Teaching Medal, and induction into the College of Fellows of the American Theatre.

Rhiannon Giddens

Rhiannon Giddens is a celebrated artist who excavates the past to reveal truths about our present. A MacArthur “Genius Grant” recipient, Giddens has been Grammy-nominated six times, and won once, for her work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a group she co-founded. She was most recently nominated for her collaboration with multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi, there is no Other (2019). Giddens’s forthcoming album, They’re Calling Me Home, also a collaboration with Turrisi, is due out this April and features songs of her heritage, sung to console her while she has been unable to go home to her native North Carolina due to the ongoing pandemic.

Giddens has performed for the Obamas at the White House and acted in two seasons of the hit television series “Nashville”. She has been profiled by CBS Sunday Morning, the New York Times, and NPR’s Fresh Air, among other outlets. She is featured in Ken Burns’s Country Music series, which aired on PBS in 2019, where she speaks about the African American origins of country music. She is also a member of the band Our Native Daughters with three other black female banjo players - and produced their album Songs of Our Native Daughters (2019), which tells stories of historic black womanhood and survival.

Giddens was recently named Artistic Director of Silkroad Ensemble, with whom she is developing a number of new programs, including The American Silkroad, an exploration of the music of the American transcontinental railroad and it’s builders. She has also written the music for an original ballet, Lucy Negro Redux (the first ballet written by women of color for a black prima ballerina), and the libretto and music for an original opera, Omar, based on the autobiography of the enslaved man Omar Ibn Said.

Giddens’s lifelong mission is to lift up people of color whose contributions to American musical history have previously been erased, and to work toward a more accurate understanding of the country’s musical origins. Pitchfork has said of her “few artists are so fearless and so ravenous in their exploration,” and Smithsonian Magazine calls her “an electrifying artist who brings alive the memories of forgotten predecessors, white and black.”

EPISODE 3 GALLERY

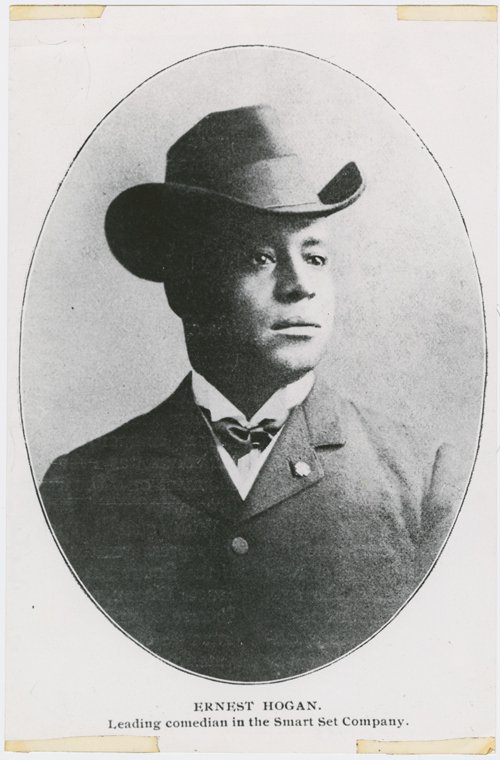

Ernest Hogan, c. 1901

Sheet music, "All Coons Look Alike to Me," 1896. The hit ragtime song of '96 eventually gave its composer the blues.

Bob Cole, c. 1898.

Trenton Evening Times, 1897. Review of Cole and (Billy) Johnson's, A Trip to Coontown.

Kansas City Star, 1898. Bob Cole in whiteface as Wayside Willie.

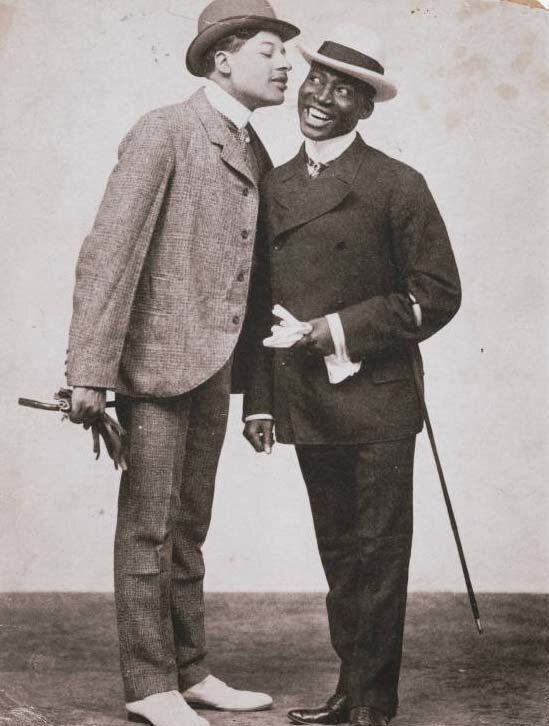

Bert Williams and George Walker.

Los Angeles Herald, 1895. A review from Williams and Walker's early days on the road.

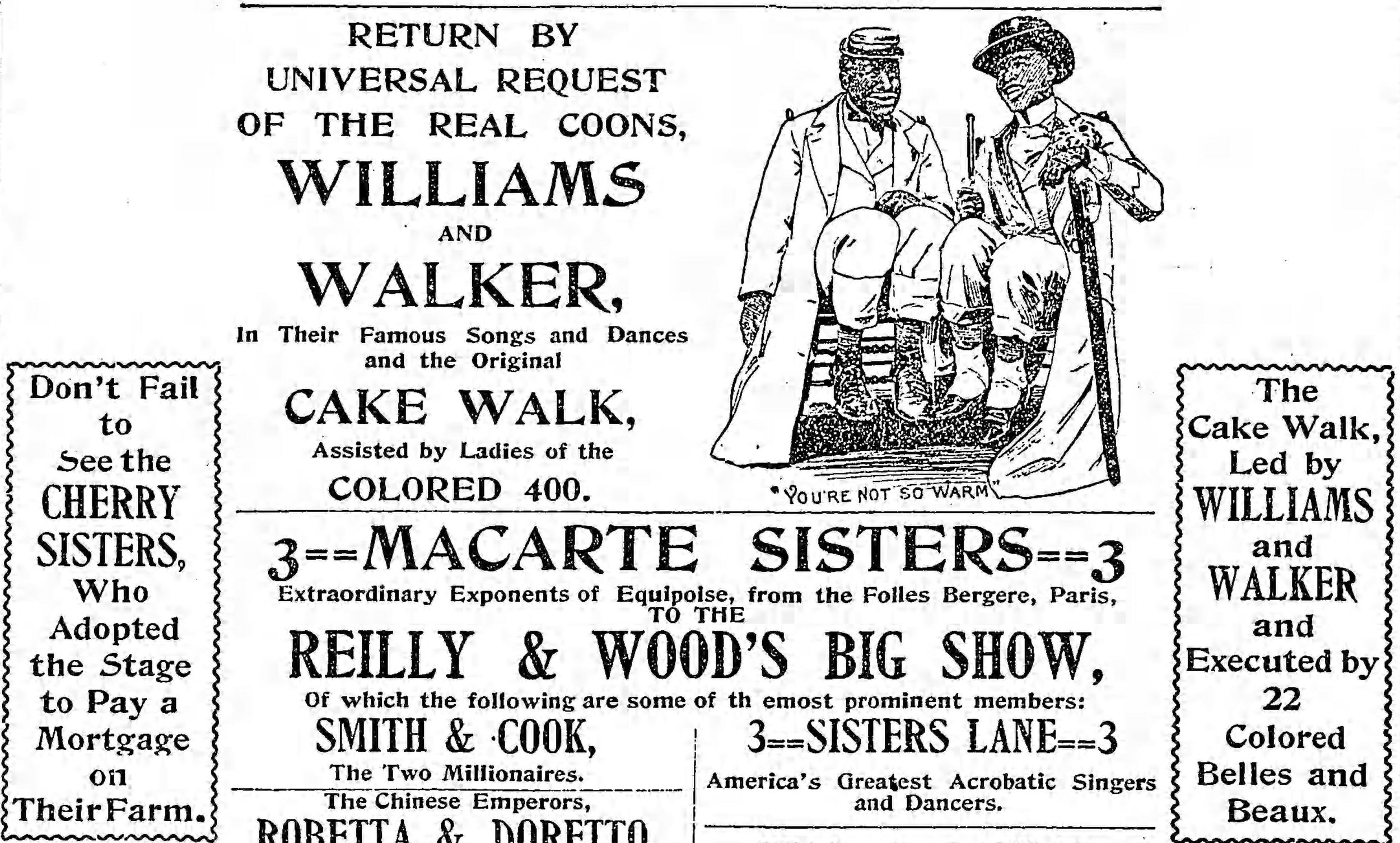

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1897. Advertisement for "Real Coons" Williams and Walker, who had set off a Cakewalk craze.

Aida Overton Walker and George Walker.

Bob Cole, James Weldon Johnson, and J. Rosamond Johnson, undated. (New York Public Library)

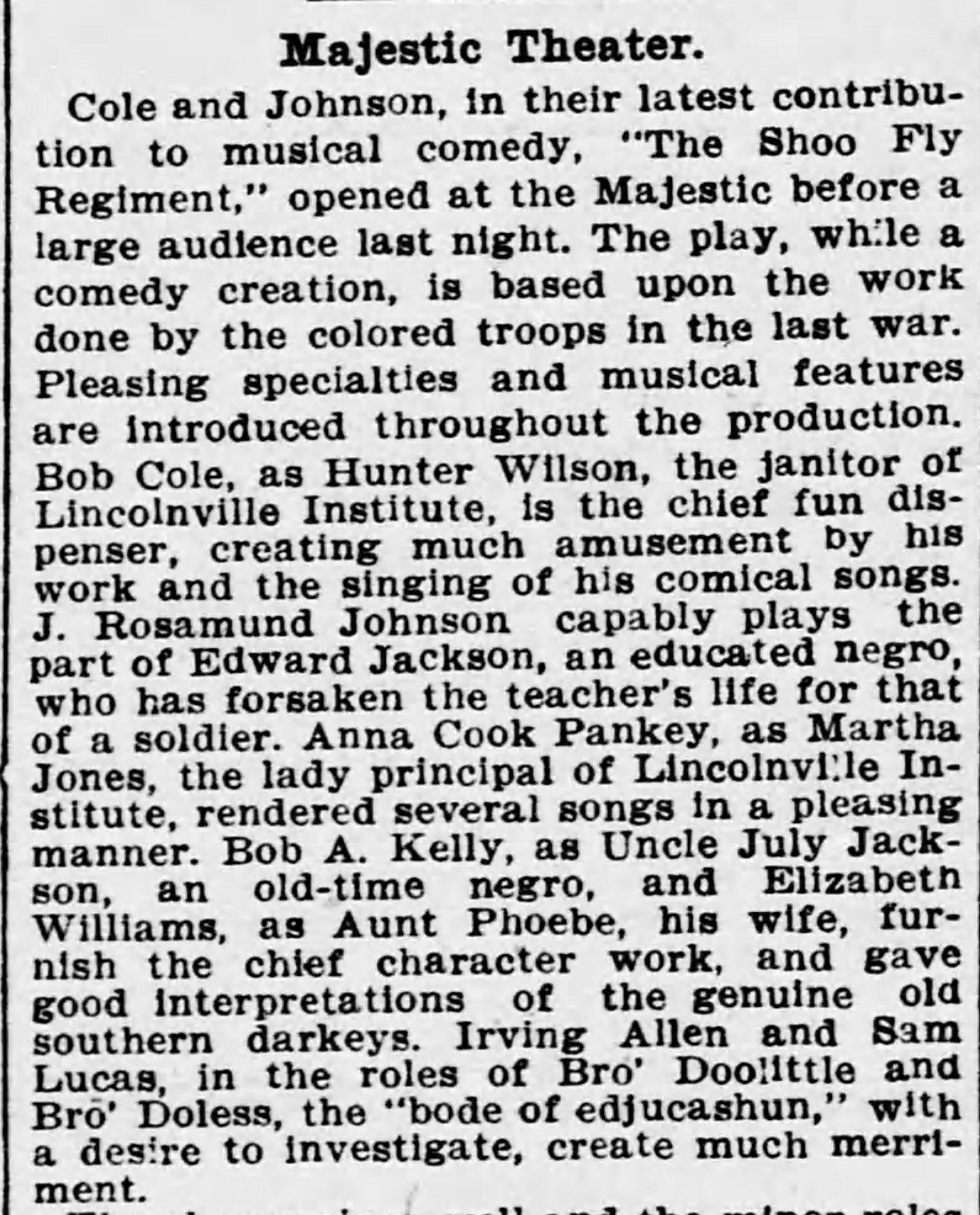

Washington, D.C. Evening Star, 1906. A review of Cole and (J. Rosamond) Johnson's The Shoo-Fly Regiment (featuring Sam Lucas!).

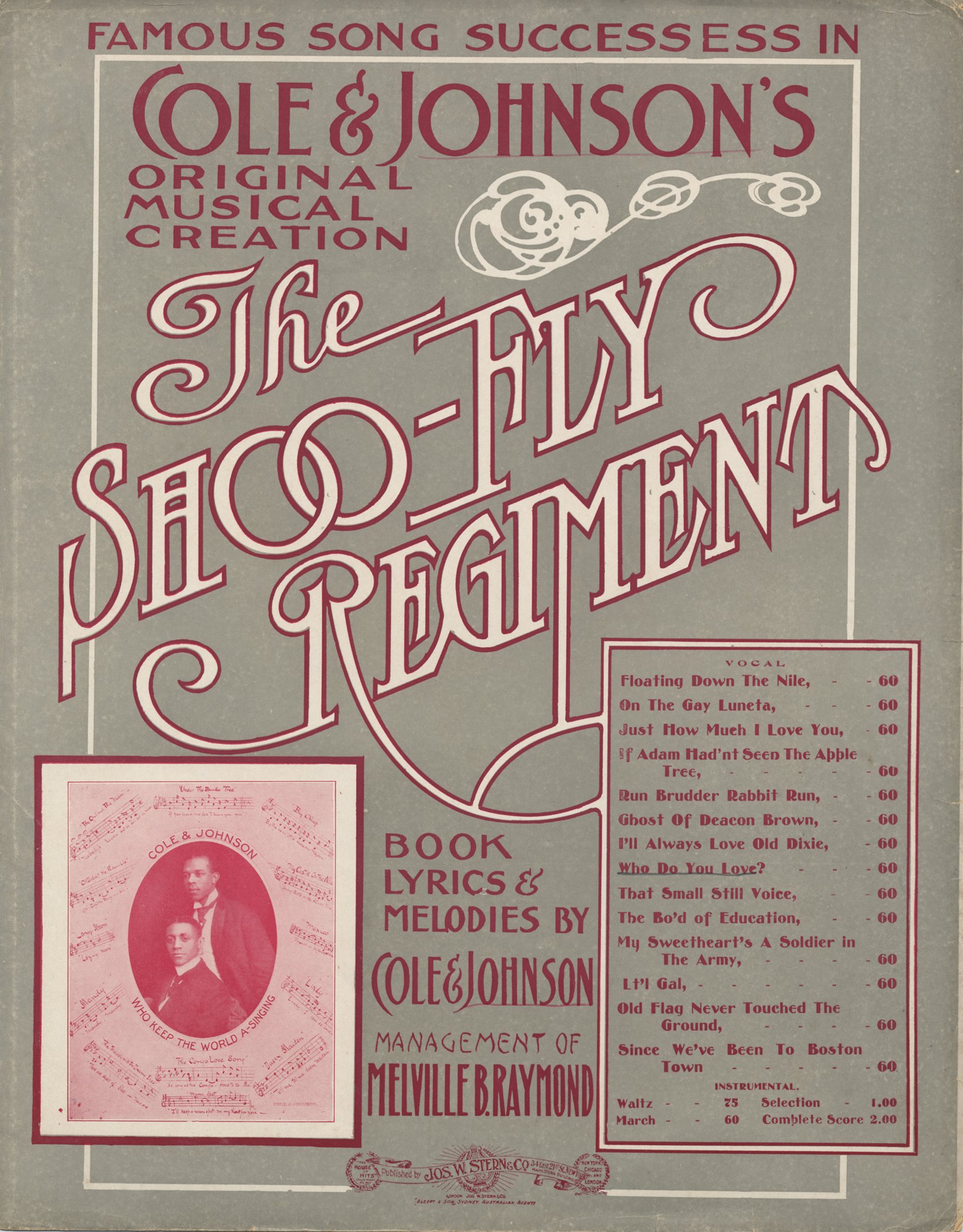

Sheet music, songs from The Shoo-Fly Regiment, 1907. With inset photo of Cole and Johnson.

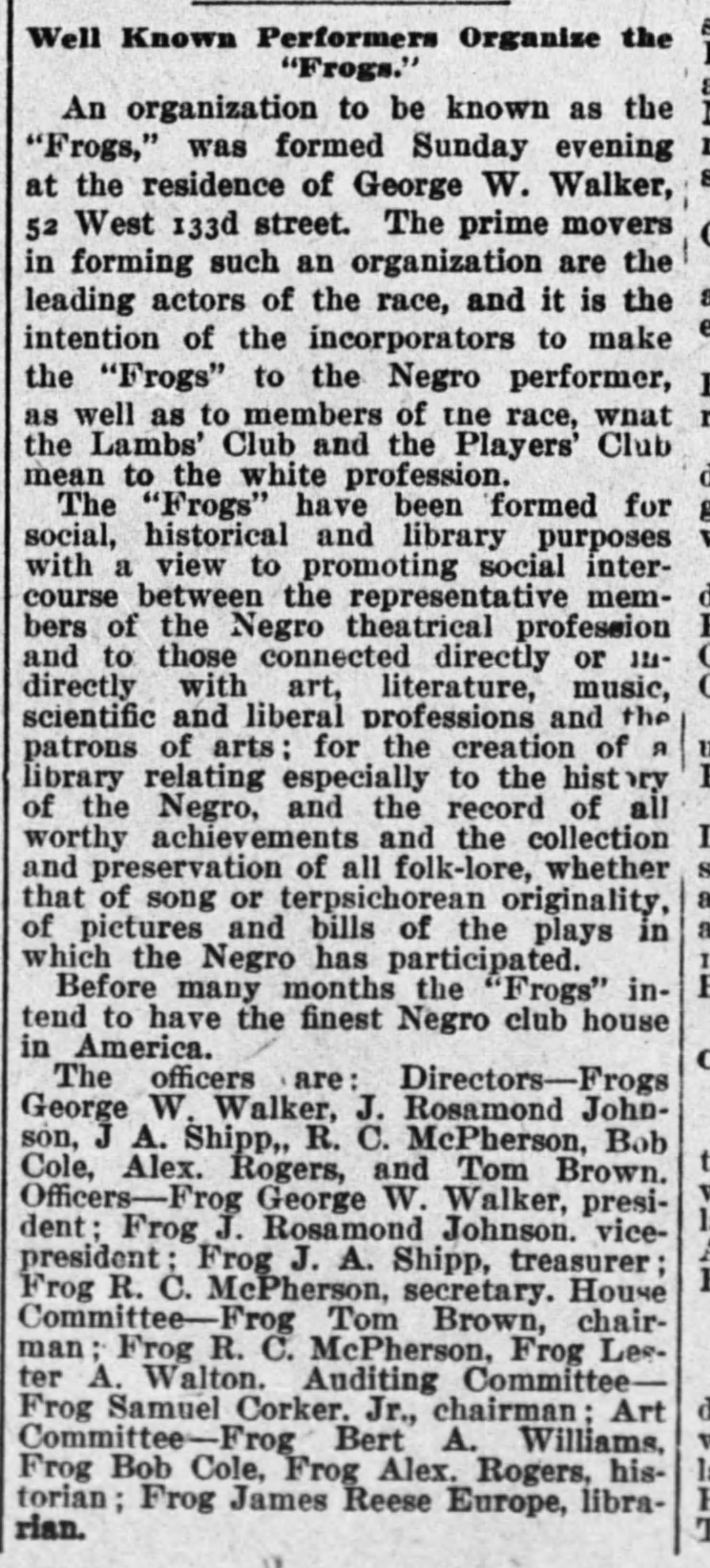

New York Age, 1908. Announcing the birth of the "Frogs" organization.

The Frogs, 1908. (Seated: Tom Brown, J. Rosamond Johnson, George Walker, Jesse Shipp, Cecil Mack; Standing: Bob Cole, Lester A. Walton, Sam Corker, Bert Williams, James Reese Europe, Alex Rogers)