EPISODE 5

In Dahomey

Episode 5: In Dahomey

In this episode the full CLASSIX team gets together for a deep-dive exploration into the 1903 Broadway musical In Dahomey.

Guests: Brittany Bradford, A.J. Muhammad, Dominique Rider, Arminda Thomas, Awoye Timpo

Featuring the voices of: Steven Anthony Jones, Kareem Lucas

Produced by: CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience

Conceived and Written by: CLASSIX (Brittany Bradford, A.J. Muhammad, Dominique Rider, Arminda Thomas, Awoye Timpo)

Sound Design and Editing: Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube

Associate Sound Engineer: German Martinez

Theme Song: Alphonso Horne

Scenes from “In Dahomey” in this Episode

Book by Jesse A. Shipp, Music by Will Marion Cook, Lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar

Excerpts Directed by Timothy Douglas, Stage Managed by Ralph Lee

Excerpt - Act 1, Scene 1: Henry Stampfield (Tyrone Henderson), George Reeder (Russell G. Jones), Moses Lightfoot (Yusef Miller)

Excerpt - Act 2, Scene 2: Shylock Homestead (Tyrone Henderson), Rareback Punkerton (Russell G. Jones)

Music from “In Dahomey” in the Episode

“Swing Along” - Music and lyrics by Will Marion Cook. Arranged by Alphonso Horne. Played by Alphonso Horne and Mathis Picard.

“I Wants To Be An Actor Lady” - Music by Harry von Tizler, Lyrics by Vincent Bryan. Performed by Amber Iman.

+ TRANSCRIPT

AWOYE Welcome to the CLASSIX podcast, (re)clamation, an intervention in the current conversation around theatre history, where we recenter and uplift Black writers and storytellers - both the celebrated and the forgotten.

As Brittany mentioned last week, there are so many ways to look at a movement. One of them is to examine the work that was made in the era. This week we want to take a deep dive into what scholar Daphne Brooks called a “pan-African extravaganza,” the 1903 musical “In Dahomey''.

Now, the actual West African empire was called Dahomey but you’ll hear us refer to it as Dahomey which seems to be the title of the show that has been passed down over the years.

We wanted to explore the production and also the world beyond what audiences might have seen on stage. How did these artists create this work? What were their ambitions and process and how does that connect to the art we make today?

We decided to get together one afternoon and chat about In Dahomey. So you’ll get to meet the rest of our intrepid team - in addition to Brittany and Arminda there’s me, Awoye Timpo, along with A.J. Muhammad and Dominique Rider.

AWOYE Hey, what's up, everybody?

ARMINDA Hi, everybody.

BRITTANY Hey!

AWOYE I thought it would be a fun challenge to see--Does anybody have a fun way to describe this play in one sentence?

Brittany I feel like all I keep thinking is like, Imma get mine. Like, everybody's like, it's not quite upward mobility, but kinda, you know, it's like, let me get mine. That's mine.

ARMINDA So I would say that it is a play, um, made famous by Bert Williams and George Walker. the first hit black play on Broadway in 1903. That it is part of the transition from minstrelsy into black musical theater.

It is about- this is hard. It is about a pair of frenemies who get caught up in a “back to Africa” scheme and find themselves on the road to and then in Dahomey that's it - it's a road trip show (laughs)

AWOYE There was an attempt I think a really very valiant amazing attempt by the great AJ Muhammad to summarize what the play was about.

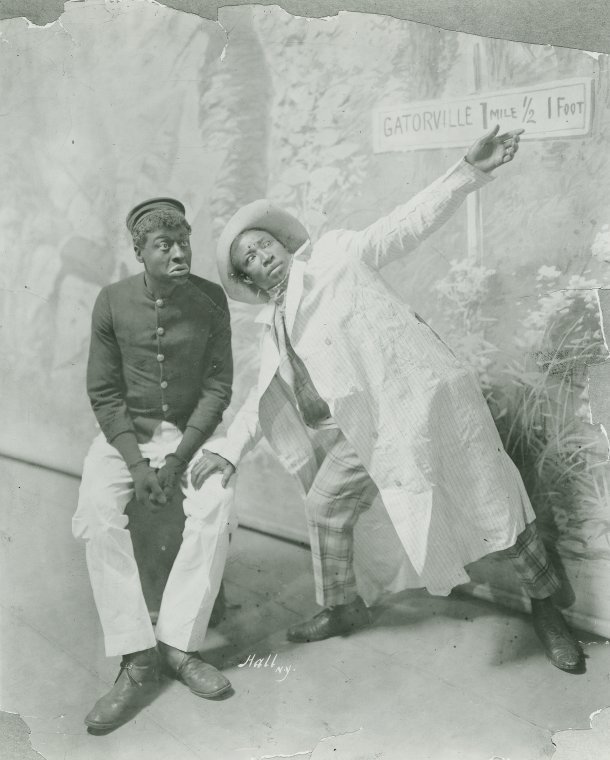

AJ wrote, “In Dahomey follows two down-on-their-luck black men, Shylock Homestead and Rareback Pinkerton, who have recently arrived in Boston from the south, and are roped into being hired to find a small casket that belongs to a Floridian man named Cicero Lightfoot, who is the president of the Dahomey Colonialization Society. Lightfoot is planning to emigrate with his family to the country of Dahomey in West Africa. A syndicate called ‘Get the Coin’ also has its eyes on the colonization society's plan to relocate to Dahomey as part of a profit making scheme. Homestead and Pinkerton head to Gatorville Florida along with a cast of supporting characters, where they converge at the estate of Cicero Lightfoot.”

BRITTANY Sounds like the plot of like a rat race movie (laughter)

(Music - “Swing Along”)

AWOYE Here is an excerpt from Act One between the characters Moses Lightfoot, an agent of the Dahomey Colonization Society, and Henry Stampfield, a letter carrier and employee of the Intelligence Office. In the scene, Moses discusses the Colonization Society’s plans to emigrate to Dahomey where they expect to make lucrative deals with the Dahomeans to bring modern technology, transportation, and other businesses to the country. Stampfield is skeptical. George Reeder, who runs the Intelligence Office also joins in the conversation.

(Excerpt from “In Dahomey”

MOSES LIGHTFOOT: I do think the colored race is the biggest set of fools I ever cast my optics against. HENRY STAMPFIELD: Hello. Mose, what are you kicking about? MOSE: Ain’t kickin’ at all. Got both feet restin’ right on the ground what they belong. I’se just naturally disgusted with the frivolities of the colored population of dis country. STAMP: You shouldn’t let trifles annoy you. I’ll dare say you’ll find the population of Dahomey quite as much a source of annoyance as the colored population of this country. Your exalted opinion of the ideal life to be found in a barbarous country is beyond my comprehension. MOSE: It’s all right for you, son, to argue that way, ‘cause you ‘specs to live and die amongst these white folks here in the United States, but the colonization society that leaves this country for Dahomey takes a different view of the matter. In the first place, we’ve ‘vestigated the country and found out just what’s what. STAMP: In other words, the existing conditions. MOSE: Yes. Everything points to success. They tell me that gold and silver in Dahomey is plentiful, as the whiskey is on election day in Bosting [Boston]. The climate’s fine - just the right thing for raisin’ chickens and watermelons. It never snows so you don’t need no clothes (pause) sich as the people wear here, and who know but what you can get a few franchises from the king to start street cars, ‘lectric lights and saloons to running. STAMP: You’ve fine, big ideas, but suppose the natives suddenly don’t take kindly to the new order of things and refuse to be electric lighted, saloon and otherwise fixed up with blessings of civilization. Suppose they look upon you as intruders and instead of receiving you with open arms (pause) make war on you. MOSE. If it comes to that, we’ll arrange with dem gentlemen like Uncle Sam did with the Indians. STAMP. How is that? MOSE. Kick the stuffin’ out of dem and put them on a reservation. STAMP. Hello, there Reeder. I’ve got a registered letter for you. I was just in the office, but didn’t like to leave it. REEDER. I suppose you and Mose were having one of your regulation arguments about Dahomey, eh? STAMP. Bye the bye, when does the Colonization Society leave for Dahomey? REEDER. They don’t go direct from here to Dahomey. They leave here tomorrow for Gatorville, Florida, where they join the main body. I don’t know when they start for Dahomey. I may go along myself. The fact of the matter is, they are in session in my office at this moment. MOSE. Just wait a minute, Stampfield. I forgot to give you this letter. It’s for my brother. You know he’s the fountain head of this whole scheme to go to Dahomey. It’s the only thing we ever did agree on. (voices arguing) MOSE. That’s the first argument I’ve missed since I’ve been a member of the Society. STAMP. Well, Reeder, if you do go to Dahomey, accept my best wishes for success. So long.

AWOYE AJ, if you could talk us through, what are we looking at when we're looking at this play? What are we pulling from?

AJ

So what we're looking at are the extant versions of the libretto. And so one of the versions was copyright in the USA, or in the US, and then the other version was copyrighted in London, because the show went to London, after playing Broadway and it was a runaway hit in London. Of course, I'm sure that somebody might have another version of In Dahomey in their basement somewhere, someone had, you know, their great grandparents who did the show. So there could be other versions of the script floating around. But, but it's very interesting, because in thinking about this, this whole podcast series and Black musical theater, I think about the technology that was available back then, in terms of reproducing these scripts. And I wonder how easy would it have been for all of these copies of the libretto to be circulating in an era where we didn't have access to the technology that we have now in terms of reproducing things.

BRITTANY Was it copyrighted in both London and the US?

AJ Yes, yeah.

BRITTANY Okay.

AWOYE

Which version of the script is the one that is printed? Is it the 1903 Broadway production, that's the one that got a first printing or…? Do we know?

ARMINDA

I’m not altogether sure. If you open Black Theater USA, it says 1902--but then it also makes reference to a prologue In Dahomey, which the 1902 version absolutely did not have. And we know that. So even the dating is a little bit sketchy. which means that even the script that we look at that doesn't have any third act, it talks about the pantomime, but it doesn't talk about what the third act is, you know, it has a whole listing of things that would not have happened until it came back from London. So it's a script that somebody was already writing on they type them out. And then you have the mimeographs, and then people like write on them. It’s hard to keep track of exactly, you know, when a script is written or what that--it's hard to follow. We can't say for sure.

BRITTANY I feel like now I care so much about having like those physical papers or wanting to be like, “I wish we could have these scripts” and but at the time that you're creating, it's just like alive in that moment. And maybe you're not necessarily thinking about? Well, it's interesting, because they were like Williams and Walker, were thinking about legacy things and having schools and everything. It's just interesting, how your story gets changed if you don't have physical, tangible evidence of it.

AWOYE Yeah, totally. And it feels like a lot of the music of the show kind of has endured. Even though there's not like a definitive version.

ARMINDA

One of the things that's interesting about this time, that is a carryover from, from, I guess, the minstrel show, and from shows like that is that the idea that the music should stay the same, it's just not there. You know, you're not going to have a set musical because you want people to come back again. And the way you get people to come back again, is to have new songs. So one of the songs that we talk about, and of course, now that we're recording, we're talking I cannot remember the name of the song.

AWOYE The “I wants to be an actor lady”?

ARMINDA 19:29 I wants to be an actor lady is in one version, but maybe not in another version, maybe not in the final version.

(Music Excerpt: I Wants To Be An Actor Lady)

ARMINDA And that's the same for Bert Williams. He had, I think, he had “All going out and nothing coming in” was in an earlier draft. So we say “This is from In Dahomey.” But the question is when and they weren't as attached, you know, they didn't think about musicals that way, it's not the original Broadway soundtrack. And we know exactly where the dips go and, and where the chorus comes in. It’s not like that.

BRITTANY

I'm reading Mike Nichols’ biography right now and in it he is talking--or whoever the person writing it talks about Nichols and May doing their comedy bit on Broadway, in--what was that--the 50s or the 60s, and how they had some sketches, but they also had some improv that would change or they'd have moments within their script that was like, “based off of audience reaction, will do this or do that.” And rereading In Dahomey, it was so interesting to see, like, they were improv artists and things were, there wasn't anything that was like, has to be set in stone, And it's like, “if the audience doesn't get the joke, here's some other language to have,” I was like, “Oh, it's so alive.” -it is taking from the minstrel traditions that they're obviously in, steeped in that hasn't quite calcified into sometimes what musical theater now looks like. And it's just, it's so interesting to me, I would love to see that come back a little bit.

AWOYE

Even just thinking about form, now when music has like an interplay inside of a story. looking at like contemporary musical theaters, it's like, this is what the setup of the text is that is going to launch this person into a moment that they need song more than anything else, to continue to tell their story. That's kind of where music lives now inside of musical theatre. But it's so fascinating in here to see it's like, “Okay, this scene happens and then boom, let's put this starring number for Aida Overton Walker in here.” You know, because it's a really, it's a really good number. Looking back now it feels quite like freeing as a form in terms of what that interplay is between the text and the music, you know?

BRITTANY

I agree.

AWOYE Do you all remember when you first learned and/or read about In Dahomey, when did you first meet this play?

ARMINDA

I did not so much meet the play as when I was working for the Davis'. And there was a lot of information on Bert Williams, because Mr. Davis had been working at some point on a screenplay about Bert Williams and was kind of fascinated by Bert Williams. So I knew about In Dahomey because in relation to Williams early career. I did not really understand the revelation that was Bert Williams and George Walker. Now it's, you know, it's this partnership and, and being part of this community and not outside of it, we don't we don't get to meet Bert Williams that way much, not just part of Williams and Walker, not just part of a partnership but part of the Williams and Walker company, which grows out of their commitment to Black art, to Black theatre, to opening their flat and having everybody pile in just that, that intermingling, which goes away later. But is such an important part of their beginnings.

AWOYE How about you, Dominique, do you remember your first encounter with this piece”?

DOMINIQUE

Yeah, I read it for the first time when I was still in college, back when I wanted to be an actor. And I was doing an independent study that was trying to understand and like, ask what Black acting methods were outside of like Stanislavski, and those other people whose names have, you know, slipped my mind. And just what it meant to be like, what was Black performance? And I, my professor at the time was like, we kind of have to start with minstrelsy, we kind of have to start with this area, we have to start with these conversations. And so we read In Dahomey. And I very quickly was like, I don't think I like this. I understand why historically, it's an important play. I understand why we talk about it. I understand its necessity. This is not really doing a whole lot for me. And so it was really interesting to reread it again, and to embrace those feelings.

AWOYE Say more.

DOMINIQUE Oh, it's just like, what--what's happening? I feel like it's a, it's a balloon. Like if you just poke it just a little bit too hard, it completely ruptures and falls apart. Which is interesting, right? Like on a thematic level that it's, it's made so loosely that it falls apart, but the thing I think I'm most interested in In Dahomey is like, why, not necessarily why we're talking about it--I understand what we're talking about it--why people are still doing it and what the impetus is for like, I think, especially directors and choreographers to want to tackle this today, like, I'd love to be able to talk to those folks. It's like, what is the thing in here that really interests you? Is it the colonialism? Is it like the, what--what is the draw for folks that’s so interesting?

AJ

Well, I think, to what you were saying, Dominique, I think that the original In Dahomey, there are a lot of ideas that are embedded that I think still resonate now we have colonialism. We have Black people talking about repatriating to Africa. There's a lot of satire in the musical about, you know, black upward mobility. We have in the first scene of the musical, this whole stump scene that comes right out of minstrelsy, which is making fun of these products that are still in the market, that are marketed to black people to assimilate in terms of, you know, skin bleaching and hair straighteners, so we're still having these same conversations well over 100 years later. So it's - there a lot of nested dolls and a lot of double entendres and slapstick and-And there's, you know, like, there's a lot of play on words. There's a lot of--there's ethnic humor there. And I think there's humor that was targeted to specifically Black audiences. So there was a lot of interplay and a lot of meta, what they now call meta theatrics, in the play, so I think it's a rich site for people to investigate and explore, because there were so many ideas that that Williams and Walker were trying to put on stage that it's such a rich body of material that I can totally see why it's still a viable thing to do.

I think we're now really beginning to get the chance to look at all this material that was created by Black artists back in the day, and they really look at it from a 21st century lens, which I think it's such a rich, you know, it's very generative.

ARMINDA

I would agree with that, I, especially when you start talking about things like the opening, it opens with, this medicine show, some speech that is, you know, clearly drawing on its roots, but we could do a comparison of that to all of the Jheri curl jokes from Coming to America. They're trying to appeal to two audiences at the same time. Because this was a segregated audience in New York. You know, you don't have to go south to have your segregated audiences, this was a segregated audience on Broadway. And the laughter came in different moments. And there were things that were just cracking up the black audience and the white people were going “He he he, I don’t know what that is.” Which we're still doing, you know, how do you tell a story that is not leaving out your home audience? But then there are some things that are very foreign to us in this script because we don't really know what it's coming from. We don't know the context because it is a play that I think is talking to its time, is talking to, it's very particular audience.

BRITTANY

It's interesting thinking of particular audience and the generational stories that are told I suppose, like I'm just imagining what it is in one piece, and maybe it speaks to the lack of cohesion sometimes because there's a lot of Macguffins all over the place in this too. But you know, the fact that you have two characters who are debating whether or not to call this white man “Master,” right, and then you have sometimes Aida Overton Walker singing the Vassar girl song as opposed to “I wants to be an actor lady,” which is all about, I mean based off of, supposedly, of this light skinned black woman potentially passing and going to Vassar this all girls school which would have been in the news And those are two completely different experiences going on and two completely different audiences that they're tapping into. And the fact that they are literally juxtaposed right next to each other, is just really interesting to me - all the elements that it's trying to cover in a very short amount of time.

AWOYE

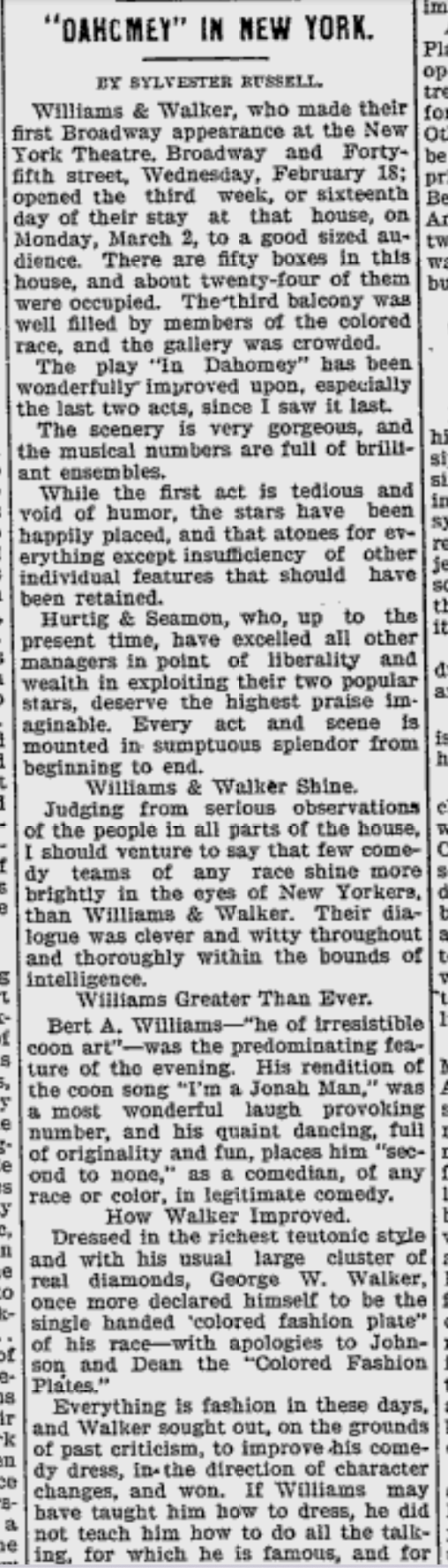

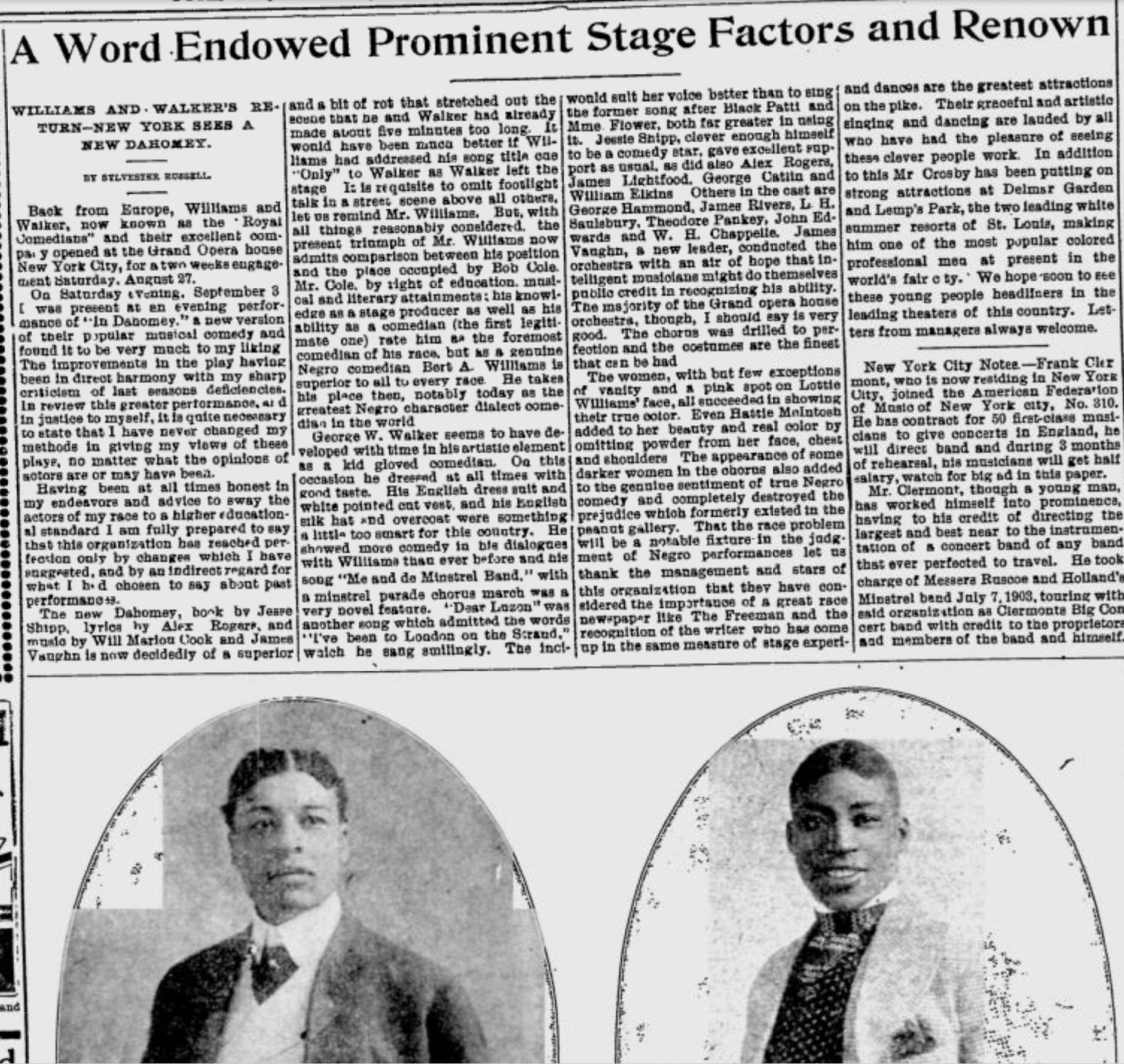

Okay, so there's this amazing character who has shown up who I didn't know anything about before we got into this, whose name is Sylvester Russell, he was a black reviewer for the Indianapolis Freeman. And he talks about the audience throughout the run of the show in different cities in the US, and he talks about how much people were loving the show, but also, you're in the presence of George Walker and Bert Williams. And so you're seeing two of the greatest performers do their thing.

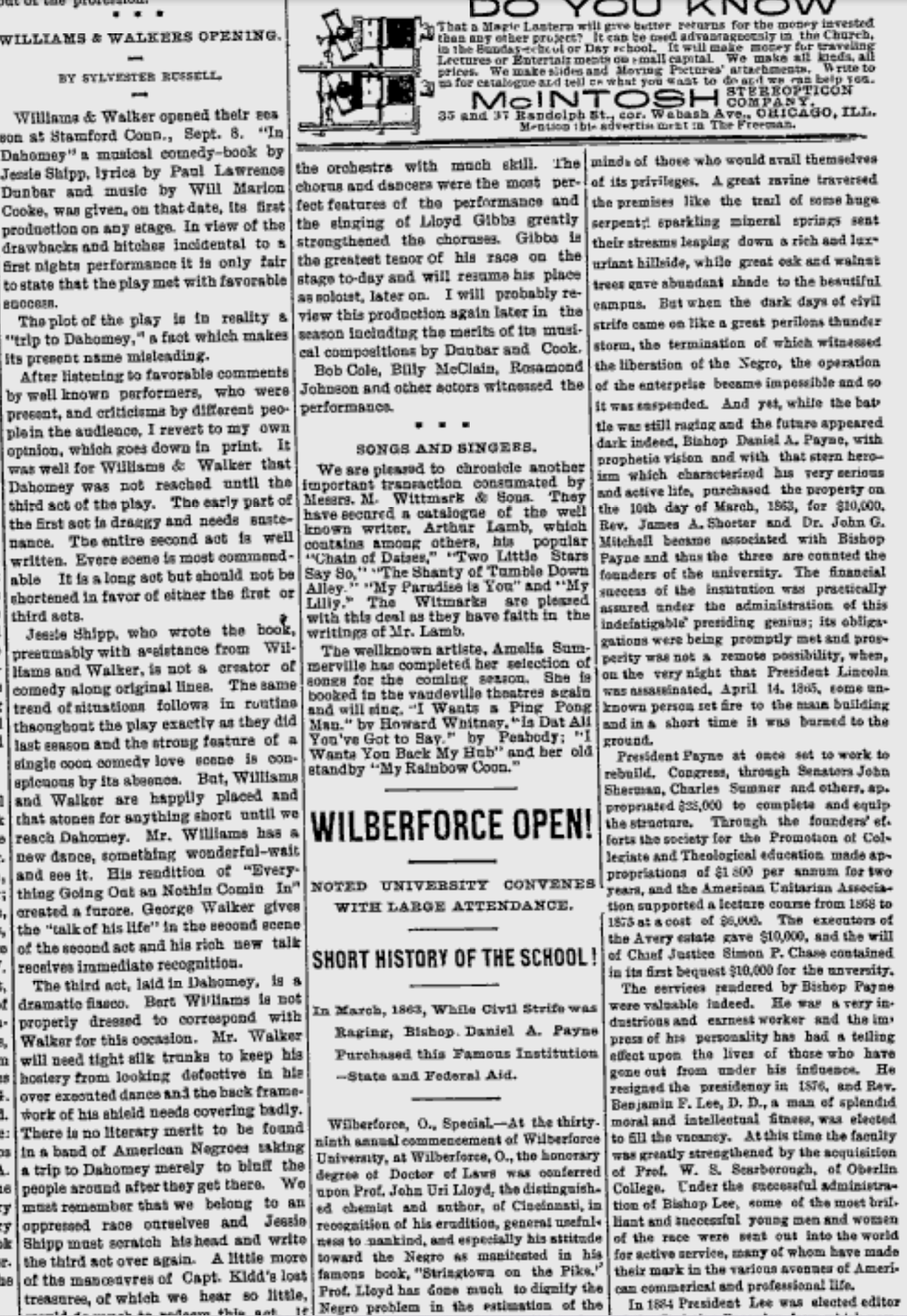

VOICE OF SYLVESTER RUSSELL On Saturday Evening, Sept. 3, I was present at an evening performance of “in Dahomey,” a new version of their popular musical comedy, and found it to be very much to my liking, the improvements in the play having been in direct harmony with my sharp criticism of last season’s deficiencies.

The New Dahomey, book by Jesse Shipp, lyrics by Alex Rogers, and music by Will Marion Cook and James Vaughn, is now in superior order. The curtain first rises on a prologue: the scene is laid in Dahomey, but it serves to open the play as it should do in the clime of its namesake. The prologue is interspersed with bright, catchy music and a drill that pleases the eye…

...with all things reasonably considered, the present triumph of Mr. Williams offers me an opportunity to compare his position and the place occupied by Bob Cole. Mr. Cole, by right of education, musical and literary attainment, his knowledge as a stage producer as well as his ability as a comedian (the first legitimate one), rate him as the foremost comedian of his race, but as a genuine Negro comedian, Bert A. Williams is superior to all of every race. He takes his place then, notably today, as the greatest Negro character dialect comedian in the world…

The women, with but few exceptions of vanity and a pink spot on Lottie Williams’ face, all succeeded in showing their true color. The appearances of some darker women in the chorus also added to the genuine sentiment of true Negro comedy and completely destroyed the prejudice which formerly existed in the peanut gallery.

The Black Patti company still has the greatest singing chorus on record...But when it comes to comedy capers, Williams & Walker have now matured at a rate that places them above all other entertainers of their race. To this I will assert that I never considered Williams and Walker, nor their company, excepting Mrs. Walker, really great until this season.

AWOYE

And I was trying to remember AJ, when you came across Sylvester Russell?

AJ

It was either in the Bert Williams, um There's a biography about Bert Williams and I don't remember the author's name. But I think Arminda had also shared that, the scholar, the theorist, the black, the theater scholar, Daphne Brooks. So she has a book called Bodies in Dissent and she writes about Sylvester Russell's reception of In Dahomey, which included quotes from Sylvester Russell's review of, I want to say, I think it was the pre-Broadway review.

AJ

Because the show debuted in Stanford and then and then, and then it went to Brooklyn, New York. And then, I mean, I think it made stops along the way, right?

ARMINDA

It went all over the place. Oh, man, it really did. It went. So it started. They started touring in September. I mean, they started production in September of 1902. And they went to, they went to Boston, they went to Brooklyn, and then they went west. So they you know, they made that whole trek before they came back to do the Broadway opening in ’03, so they basically did six months on the road, because I think they opened in February of 1903 on Broadway. And then in April, they went to London. And they were in London for eight months? And then they came back and did like a two or three or four week run on Broadway again. Or in New York somewhere...

And then they went throughout the country again, you know, with the 1904. They toured this thing from 1902 to 1905. They were doing In Dahomey.

AWOYE It's no wonder that like us trying to piece together like what the show was, is so difficult, because there must have been like 100 different versions of what the show was over the course of those couple of years. And maybe this is kind of our approach to all the plays that we look at. But it feels like there's kind of two sides to it, right? There's like the interior of the play, like what are the actual events in the play? What's actually happening? And then it feels like there's the life of the play outside, like what the, what the creators were trying to do with the play.

BRITTANY

I mean, that's the thing that I love the most about, I mean, I'm, you know, I always talk about like, the Marshall hotel, and how I, I feel like people should talk about that more, which I don't even think we talked about enough, but this hotel that was like, owned by this Black person in the, like, the West 50s where all of these, you know, Black artists and intellectuals and, and you know, the white people who wanted to be cool, but like, come in and, and talk art. It's just, it seems like such an exciting creative time. And you think it's happening in like the early 1900's is like really fascinating. And it feels, I just feel a lot of ties to now in the sense of, we don't, we don't know what this can be. We don't know what this art form is right now. So let's just play and crack it open. And let's have Paul Laurence Dunbar come on in and, and do stuff. And let's work with Williams and Walker. And let's do all of these things. And it feels like, I don't know, coming out of the pandemic that maybe not everybody is having this conversation on a large scale. But in small groups, there are people that are making art who are like, okay, we have to come back and it has to look different. So what can it be? And actually, that's a really exciting time. And as AJ said, it's generative, there's something about it that is like, this can be literally anything we want it to be. So let's just play and it doesn't become calcified yet. And that's super exciting to me. And there are absolutely moments that do not work. But maybe it is that I'm more interested about the making of it than the thing itself.

DOMINIQUE Well, Brittany to your point, right, like what's the most--what's the best part of doing a production? Is it the nights you're on?

BRITTANY Process

DOMINIQUE Exactly.

BRITTANY

That's--to me. It's the process. Yeah. Which is not the same. Everyone doesn't feel that way. And that's fine.

ARMINDA

I mean, the thing that kind of captured me was this attempt to incorporate Africa? And, you know, some part of and to think about black Americans’ relationship to Africa, what they, you know, what they thought about it. You know, when we think of the American colonization society, we think of, you know, kind of pre-Civil War, white people trying to figure out how to end slavery by sending all the black people back, and, you know, maybe a couple of, rich and black people going, Yeah, that sounds like a good idea. Let's do that. When reconstruction fails so horribly, why would that not be a possibility in people's minds, but, you know, I, I came to this piece and, and read something that said, you know, this was about the, this talked about the Turner Affair, and I'm like, What the hell's the Turner Affair, I don't even know what that is. So, you know, and, and then you go, you know, follow your little rabbit hole into Henry McNeil Turner and discover, you know, this guy who was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which was a big deal, you know, who was one of the early, early proponents of female clergy, who was one of the early proponents of reparations, and also of, letting black folk, particularly in the south, just get out of here, because what does this country have for you, jack shit, nothing, there's nothing here but a denial of your rights. And the best way to, to get around it is to get out.

And so, you know, a lot of this plot is in fact, based on this man, the guy who responds, it's not Cicero, it's the other Lightfoot in the first act to who is very upset with these people, for buying up these hair straighteners and skin lighteners.

Turner had no patience for black people who did not love themselves. None. None.

VOICE OF BISHOP HENRY M. TURNER) When I was a United States chaplain, appointed by President Lincoln, ten thousand balls were sent whizzing around my head, but God protected me, and only God has enabled me to live since, amid mobs and Ku-klux, and not because the nation I tried to defend, when it was on the verge of being torn to pieces, offers my person any protection. Yes, I favor emigration for my race. Let them leave a cruel and ungrateful nation like this. I honor your ancestors for leaving oppression and coming to a country where they could be men. And I advise my race to do likewise, and if that makes me an old fool and a mischief-maker, thank God for the honor of being a fool. I am a fool and mischief-maker because I am not willing for my race to sit down and quietly be murdered in every conceivable form and for the nation to say well done by its silence. A fool because a savage country can outrage and murder my race in every manner, and I am not willing to hold my tongue while it is being done."

AJ

If you look at the project that Williams and Walker and the company were trying to do, I mean, it's, it's very ambitious. And surprisingly, I’m wondering. So they wanted to create a series of musicals, original musicals for commercial theater with all Black creative teams. Like, that's not even happening now. I mean, there's work that's being created, but we're getting a lot of jukebox musicals like Motown and then Soul Train. But this, Williams and Walker was saying, I want to create, you know, original books that were original stories. It doesn't seem like they're a group of Black producers who have been galvanized to say, I want to bring original musical theater pieces to Broadway now. You know, so it's a very interesting conversation to look at how, you know, how advanced and how forward thinking they were, you know, notwithstanding the problem in the material, but if you, you know, if we look at this 100 years later, we can say why, you know, why isn't there someone doing that sort of same work that Williams and Walker are doing? There are Black producers who are in commercial theater now, but where's this - Where's the conversation around bringing original plays and or musicals to Broadway and not have to be filtered through the white gaze of a white producer, or white creative team?

DOMINIQUE

Or of white people's text, right? Like in the case of the Williams, right, like, whose words are you saying, whose words are you putting in the mouths of black actors and asking them to say?

ARMINDA

And that they're not alone, that at the same time, Williams and Walker are, you know, doing this, you also have Cole. You also had Bob Cole, who, at the time of In Dahomey, has taken a little break, but who started, who started it off in New York with-- A Trip to Coon Town and then got to, and then later with the second Johnson set, with Shoo Fly regiment and with Red Moon, which were much more, I think, developed pieces but also struggled. When we were trying to figure out what play we were going to be looking for Cole and Johnson mounted a serious challenge. We had issues finding scripts, but also, and that might have been partly pandemic, we have issues finding scripts, but I think also he had a bigger target on his back because of the Black Patti producers and you know, he managed to, to pull off a lot, even while dealing with active hostility. You know, there was a hostility with them that Williams and Walker I think did not face in the same way. And also Walker was just a great businessman and managed, you know, these things.

AJ

I do want to say that Williams and Walker still got caught in the vortex of white theater of the white theatre syndicate, because I remember reading and doing research for this episode that they, Williams and Walker wound up suing, I don't know, was it like the theater, the white theatre syndicate was Erlanger and somebody else. Also, when they were saying that this group of white syndicates was keeping them out of theaters in the Time Square district and making them go to the ‘50s. So there was a whole court case. So they weren't, you know, completely, you know, outside of that. Like you really couldn't escape the machine. And, you know, we can still see vestiges, vestiges of you know, this, you know, now in the 21st century.

BRITTANY

That's the, see, that's what I have a question about, and I'm curious what you all think, because, as you said Awoye before, there's a lot of breaking a form that happens within this piece, or within this time period, where people are, you know, making that transition as to like, what is minstrelsy? What is vaudeville, what is music theater, what, and playing with the structure and Ragtime, and all of these things, it reminds me a lot of jazz, right? It reminds me of like, a very controlled chaos in a way that is exciting, of breaking down forms. And when I think about this with the 21st century lens, I do think, oh, well, minstrelsy seems like such a stifling form, obviously, like, I think, Oh, these black artists working in this form, that must have been terrible. Obviously, the art we're making now is more creative or revolutionary, or whatever. But when I look at this episode, and think about now I'm like, Is that necessarily true? Like how many artists, because this is mainstream. This, like, This piece is popular? So it's not like in some backwoods? What a-- that sounds so diminishing, but it's not like, you know, where everybody is not seeing it. It's very, it's popular, and it's a little chaotic, and it's a little messy, and it's like trying new things, and it's out in the mainstream. And I'm just thinking, is that happening with black art in the same way now in the 21st century? And even what AJ’s saying about white, like the fight with white commercialism? Are there a lot? I don't know, are there a lot of Black--? Like, how much of it is, how much are people--What risks are being taken now in the commercial realm that Black people are making? How many people are really, really going at it in that same way? How much form is being actually broken in that way?

AJ

I mean, I think, to your question, Brittany, there are people who probably will say that they're doing that and I can think of some names, but I don't want to go down another rabbit hole. But that certainly is, you know, a conversation because in, in our pre-planning stages for the, for this act, we talked about the work that Tyler Perry is doing. So that's a whole ‘nother conversation. I think that there are people who can make a claim to that, but you know, yeah, I don't know what the answer is. But to your point, I do think that there are people out there who can, Oh, yes, you know, I'm doing that in my artwork. Absolutely.

DOMINIQUE

You know, Brittany, I feel like to your point and to your question, one thing that I feel like I encounter a lot, right, is people who say that they're doing that thing. But what they actually mean is that they are just Black, right? Like there's talking, they're talking about their art being genre bending or experimental. And oftentimes, what you get is like, Oh, this is a table drama, but with Black people. Right? And that seems to be the extent of the sort of, their idea of what revolutionary art can be, right? When we know that there are people currently, when there are people, right, like in the times we’re talking about pushing it. And I think that, you know, Professor Ayanna talked about this a little bit, when we first interviewed her. With that question she posed that I haven't been able to stop thinking about, which is right, Tyler Perry must believe that Black people have control over what they believe are funny. And I think that that's like a very interesting idea. Because I think that in the same way that the Black body is fungible, can be used for any purpose anytime, anywhere, the Black mind occupies a similar space, right. And when you start to, when you begin this process of making art, and I think even just being someone who exists in white institutions, if you like that sort of thing, what you get tricked into thinking is that sometimes being black is just enough, right? That just being a black person in a white space, is the sort of be-all end-all of what a revolutionary politic can be. And then like you're black in the white space, but like, are you replicating the same types of policing, the same types of violences that are being enacted on you to other Black people, right. And I think that art, art happens a lot in the same way where you were, when people, you write the play that you think is most easily going to be produced. And you just keep writing those, right? Because it's, because of the way capitalism works, the way that anti-Blackness and white supremacy function hand in hand, you start to, I think, you get to this place where it's like, oh, I'm just writing this so it gets produced. I'm just writing this so it can teach generally white people a lesson. There's a play going to Broadway where the playwright admits that was the entire impetus behind the play, right. And I think that until we can, not like, there are certainly people who are doing something else, I think of “what to send up when it goes down” is an example of that, right, by Aleshea Harris. But I think that oftentimes, what you're seeing on a commercial front, are the things that are safe, things that are the most easily producible. Because it is never just about the art. Right? It becomes like what is digestible? What do the people who are coming to the, coming to Broadway, which I kind of think, we should just move on from at this point, but you know, so what do these audiences need? What's going to get someone from a family in Texas to come see this play? As opposed to really, I think thinking through this whole regional model in the way it exists, what do the people in Texas need? Right? Everybody don't need to see, I love it, but everyone doesn't need to come see the Temptations, right? There are things that can be made locally, that can be made, organically that might be, that not even might be, that are going to be better than what we're seeing time and time again, on a Broadway stage. Because what does Broadway have the space for? A specific type of musical and like, a specific type of play. And one anomaly I think proves, like, like, I feel like we get one anomaly every so often, that anomaly proves the rule. Right? And so I felt like, it's like, it's a very complicated question, especially when we think about what Broadway is today that it didn't used to be. It's a capitalist deathtrap. Like, it's being like very nice about it, right? And so what do you get in those capitalist death traps? Well, you get replications of the same thing over and over again. And then you get someone looking in your face who loves Broadway. And it's like, capitalism breeds innovation.

BRITTANY It's okay, this is interesting. There's, obviously so many wonderful things that you just said, as a personal anecdote that's making me think of this, right. And as you all know, starting this new job that's going into TV, and I had conversations all week with people being like, well, you have to get - You're doing this so you have to be incorporated. And you have to get a business manager, and you have to get a publicist, these are just things you have to do. These are things that you do, and I will say also, all of these people saying these things to me are white, you know what I mean? So that's, that's also part of the, the dynamic that's happening. I've never done this before. And so it's hard to be like, Oh, I guess I don't know this. I guess I have, is there, are these things I have to do? And then laying down at night and being like, what does that mean? I have to do it? And what does that mean to like said, because it's been done, because what these white institutions, because all of these other people found success in it. So if I want to find, you know, it's having that constant battle of what does it mean to have to do something? What does it mean to say that this is the system that's in place, if you want to operate, period, you have to operate within the system, all of these questions and looking at this play, even as looking at this whole Black minstrelsy, all of it, thinking about what Broadway means back then, thinking about what it means to be a Black artist back then, it's just putting more context of being like, you don't have to, there's no should, like should is something that just needs to be taken out of the vocabulary as much as possible, especially when the systems aren't in place for you, for us.

AWOYE And the thing I would add to the brilliant things you and Dominique are both saying is, I think this is a thing that's so captivating about Williams and Walker, and all of their kind of compatriots. It's actually two different questions. Are these things actually being created? And then what are the things that are being produced? Right, the artist on the ground, there's so many incredible, magnificent artists who are attempting to make great work, however, there is this pull into kind of like the illusion of the larger, of the larger system that is very individual as well, right? It's like, as Dominique is saying, you're, you know, you're the single Black playwright inside your MFA writing program. And so then your purpose and function becomes a very different thing. These guys are talking about how do we build ourselves a community where we can make our own rules where we can say, these are our ambitions, and then actually build towards what those ambitions are, and actually continue to harness other people around them to break through what the, what the kind of larger illusion of the system is, to the, to the point that they were, you know, able to kind of create this piece that thankfully, we're able to look and see what they've done. So I feel like there's two parts of it. There's both the, what's the impulse of the artist? There's what's the impulse of the capitalist theater system? And then there's also what does it mean to operate as an individual versus operating as a community? These guys were building an army.

BRITTANY And what does it mean, though, that this all went away? Do you know what I mean? Because we talked about the fact that black minstrel, that all of these initiatives, all of these things, all of a sudden, there was nothing that was being created after a while. So what was that also?

ARMINDA

I would say the caveat, I'm sorry, the caveat, these were things that were not being created on Broadway. I mean, they were that were no longer making it to Broadway, we were getting, what we were getting was, we were getting the, the beginning of a circuit. I mean, there was the beginning of a, of a black touring circuit, which eventually became the TOBA circuit. So there was, so there was work, like there was some work in Chicago, there was some work, there was work being done, but not to scale. Right. You still had these people creating and inspiring in ways that we, you know, don't always see inspiring the Harlem Renaissance you know, but in the retreat--maybe it happens even if George Walker doesn't die, but it hadn't yet. You know it, but it takes a lot. It takes so many factors to be able to knock down that wall that even as small even, you know, a first layer of wiping off knocks it down, but not out. Right? We were beginning to break through on this stage, at, you know, in a very large way in New York and then on Broadway, which in itself was kind of the new thing, right, but we were beginning to break through on a large level and then that is gone for at least a decade. And then gone again for, you know, quite some time then yes… That's definitely, it's definitely analogy. It's definitely, you know, an era that died down but that, they got banked but you know, fires that are banked are still, are not dead. Right? Is that right? Is that true? Or did I just mess that metaphor up? Anyway.

BRITTANY What were you gonna say, Dominique?

DOMINIQUE Oh, I was just thinking about right, the linkage that you're pointing to about like, the disappearance, right? The Disappearance of these things. And similarly thinking about when you start to like years later, which might be a good podcast episode one of these days, the sort of disappearance right of Black theaters as physical spaces. Right and, and the, Saidiya Hartman - because you know what this is - has this quote where she talks about the Black feminist tradition exists to be rediscovered, right. And that's so often seems like what we're having to deal with is black, I think Black anything period, but because of the niche-ness of theater, Black theater artists and practitioners, so specifically, of like, how do we, how do we maintain this legacy? And maybe more importantly, how does this legacy maintain itself? Even when we're not able to see it? How does it go underground? How does it go underwater? And how do we discover it again? Years later, right? I think it's such a, this sort of, the disappearance of Black theatre is such an interesting conversation to have, it feels so there isn't, I feel like you can just yeah, it's like we can go any time period we want and, right? Then it's like Black people doing x, it disappears. And how do we uncover that, but also make sure the disappearing act stops.

BRITTANY

It's kind of like the Odyssey. And that way, it's like, taking that--thank you so much. But if you're taking that journey, and there's all of these, these, these, everything it's trying to stop it or to change it into something else. They want it to be what works for them, and to hold on to that the entire time to take that torch to the next generation and still have it be the fire that you created way back. That's, that's a really hard ask. And then to do that, and like Harriet Tubman it and bring everybody with you. That's another journey like that. There's so many journeys to do that we’re that were being asked to do, it's hard. I'll just say it's a lot of work.

DOMINIQUE And just to speak on Harriet Tubman. Don't forget that she also shot some people. That is, that is also equally as important to hold right.

ARMINDA

Yeah. She at least threatened…

DOMINIQUE And sometimes, you know, that's what it is. I feel like that's where we are, is they've been like, but you're thinking about your question, Brittany, it feels like we are in this period, where there are so many people who you just feel like want to try new things. There are so many artists, so many writers, so many directors, so many actors who want to be asking you questions, but have been disciplined their entire careers, right? Because again, what did Hartman tell us the whip didn't disappear, it was internalized. How you get disciplined into fighting against the things that, you know, might save your life, right? Especially when the things that might save your life, are going to give you less money than the things that continue to kill you.

BRITTANY Yes. How easy it is to convince yourself to become an individual, individualistic, egoistic, capitalistic individual, like a person, especially being a black person to be like, well, I got mine. Yep, I got like, that was enough work. Just that was enough. Okay, so let me convince myself or let other people tell me, it's like the OJ saying, I'm not Black. Right? Let me, so that I can just survive in this world. Because it's hard enough. It's really hard to continually bat down those walls and back down that, that like reinforcement and negative reinforcement of you're now in our sphere. So you don't have to worry about that anymore. You don't have to question that anymore.

AWOYE To me, that feels like one of the actually very reasons to be looking, that the investigation into the play is actually caused me into an investigation into a time and into a time that's about an investigation to a way of thinking about the world that you live in, and who you are in relationship to other people that feels like that's part of the invitation of what In Dahomey is, you know, it's an invitation into understanding what these people were trying to build… Does anybody have any final thoughts that they want to get in? Before we close out for the afternoon?

ARMINDA

So um Ossie Davis, gave a speech before the Congressional Black Caucus. And, as it was formed in 1971, and the theme of this speech was, “It's not the man, it's the plan.” And it came after a wave of, you know, of assassinations, and trying to build and regroupings and, you know, leaders who had fallen or, you know, leaders who had fallen. And the idea was that, you know, you can't trust in, you know, you can't put your faith in the one person, in the one visionary, in one thing. You have to, as a community, have an idea of what your goals are. And I’m thinking about this in terms of George Walker, and thinking about this in terms of Bob Cole. I’m thinking about how often you know, or August Wilson, you know, or Woodie King. Or, you know, what is it to, to have so much of the thing that keeps you going, residing in a person, a person's vision, a person's, one person's ability, with Walker, I mean, there was a group, but who had the vision for what it was supposed to be. It's not that Bert Williams just abandoned it, he, he didn't know how to keep it going. He didn't know how to keep it going. And so when everybody has a position, you have to have people who know what that position is, people who know how to play that position, people who know - I think about this in terms of Classix, but that's a different conversation. But you know, it's important to have people in on the plan, people in on the vision for, for politics and for art and for in, particularly, you know, for, for all things Black, to have, to have that community that is not around the person with a vision, but the vision has to be held. It has to be held. And then you have to because things happen and life happens and death happens. And you have to figure out how to move forward.

AWOYE

Yea, AJ, do you have any final final thoughts?

AJ I think that, I mean I keep saying this, but there's so many ripples or the ripple effect of what, of looking at, you know, the Williams and Walker, you know, Cole and Johnson, and all these other artists, and we're still feeling the ripples of the work that that generation was doing way back when and we’re still asking the same questions about legacy and leadership and succession. I think, you know, all these conversations, you know, come up and I do think it's a great takeaway. I'm just fascinated again, and by the, the project that Williams and Walker were trying to do and how we can tie so many things back to, like that was, that was a vehicle they, that they used then that we can tie, you know, tracks to today, which is really fascinating, because, you know, black artists, we know the black art, you know, it's timeless, and you know, and it's always relevant. And so this is a good opportunity to remind ourselves of how brilliant we are as creators and as originators and how we, you know, we come up with things then get appropriated and taken and stolen from us, but it's just, it's an example of looking back at how forward thinking and innovative the work was back then and how it's still, you know, even though, even though like if someone said if you poke it, it falls apart. This still, like the part that falls apart. if you caught that, It's still, it's still valuable.

DOMINIQUE Absolutely, it is.

AWOYE

Yeah. Well, I think that's a beautiful way to end. Thanks so much, everybody. Always amazing talking to you all and we'll talk soon, later.

Next week is the final episode of this act.

We heard so many wonderful actors in this episode including Tyrone Mitchell Henderson, Russell G. Jones and Yusef Miller. The scene excerpts were directed by the incredible Timothy Douglas. And please check out the website to see the full list of actors who have contributed their voices over the past five episodes.

For more information on Black Performance in the era of Minstrelsy, please visit theclassix.org and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @itstheclassix. This episode was produced by CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience. Our sound editors are Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube. The theme song was composed by Alphonso Horne. And Swing Along was arranged by Alphonso and performed by him and Mathis Picard. I Wants To Be An Actor Lady was sung by Amber Iman. For full versions of the songs and another excerpt from In Dahomey please visit us online. Special thanks to Daryl Waters and Woodie King, Jr. See you next week.

Related Article

“The World According to Sylvester Russell” by Dorothy Berry. Lapham’s Quarterly, 2021. (Link)

EPISODE 5 GALLERY

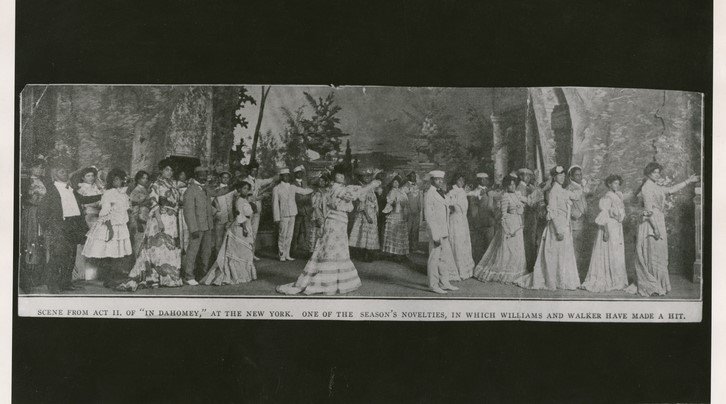

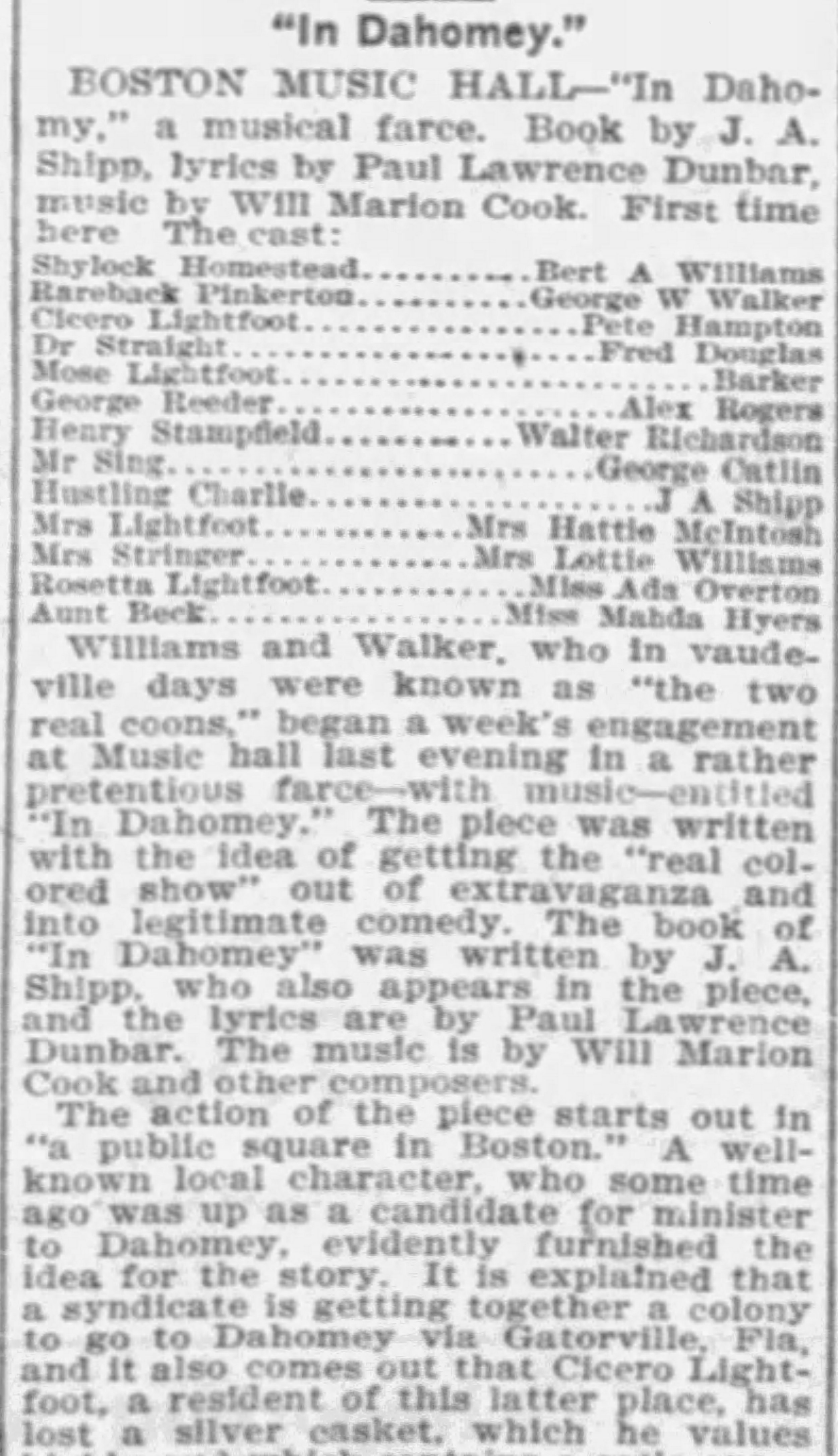

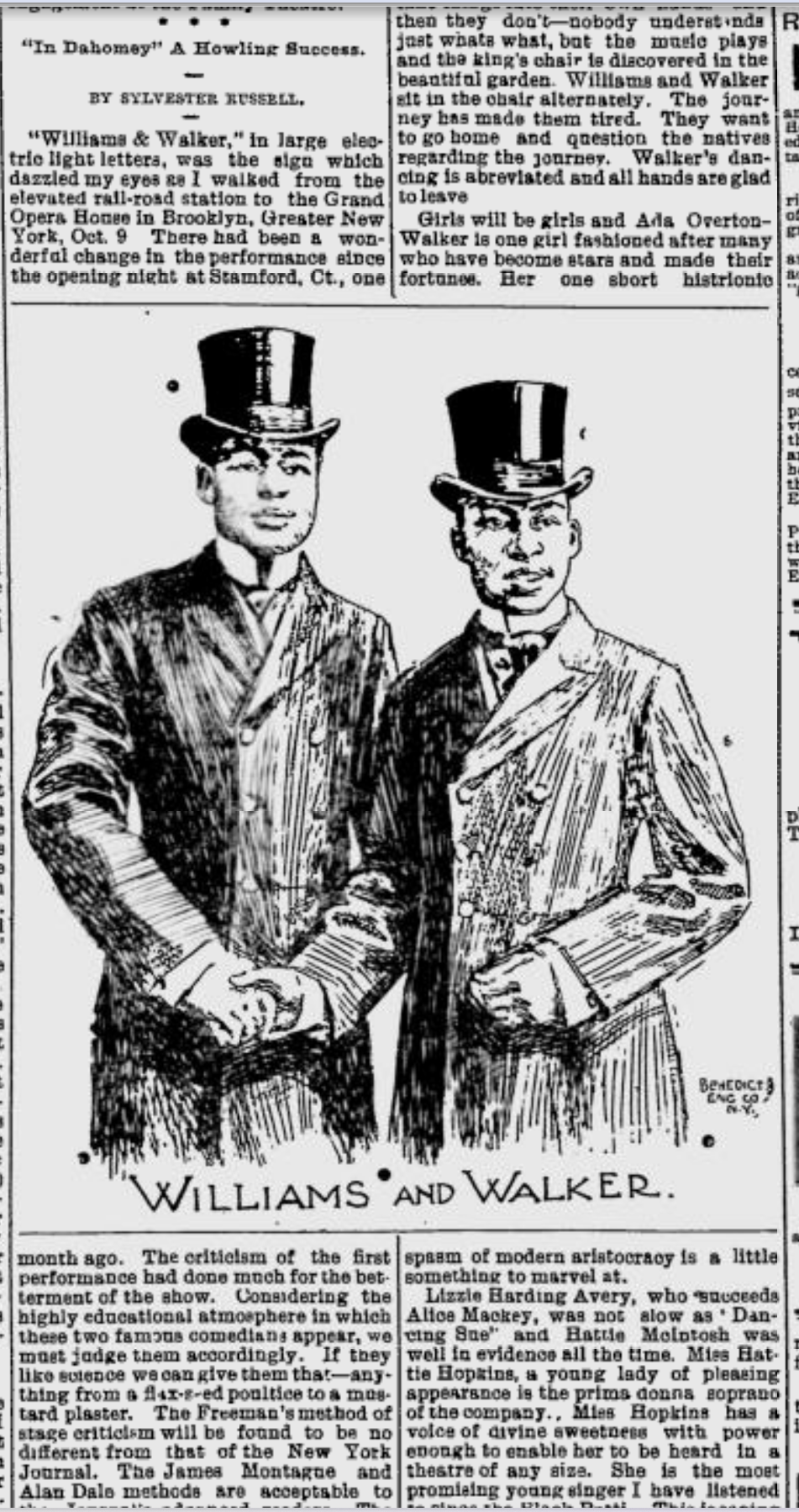

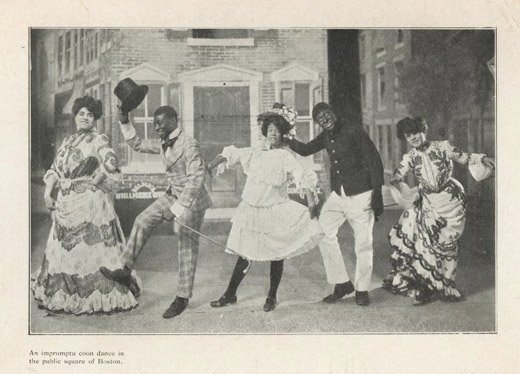

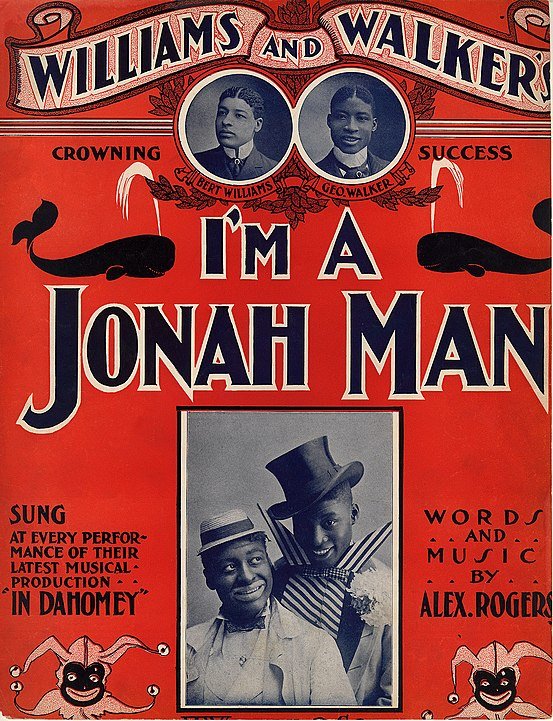

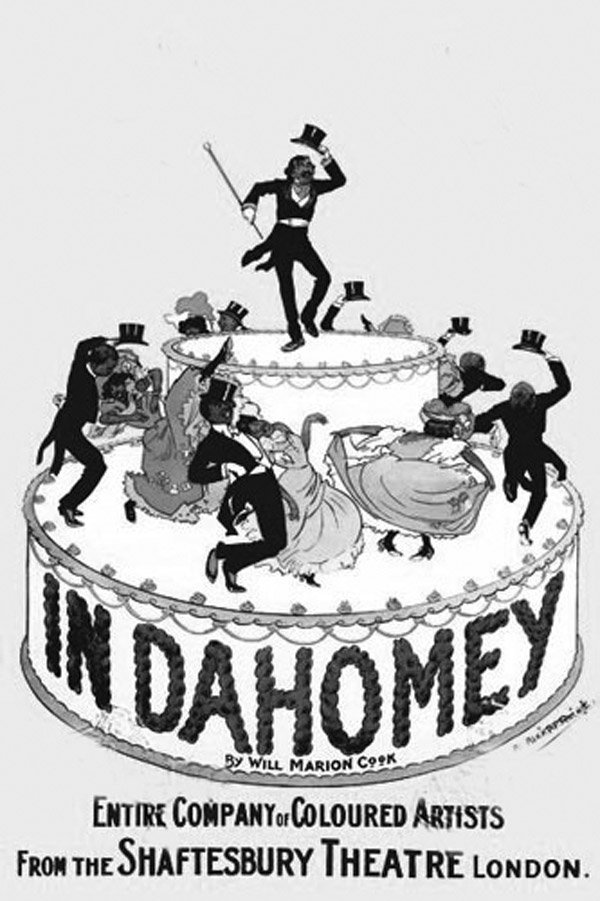

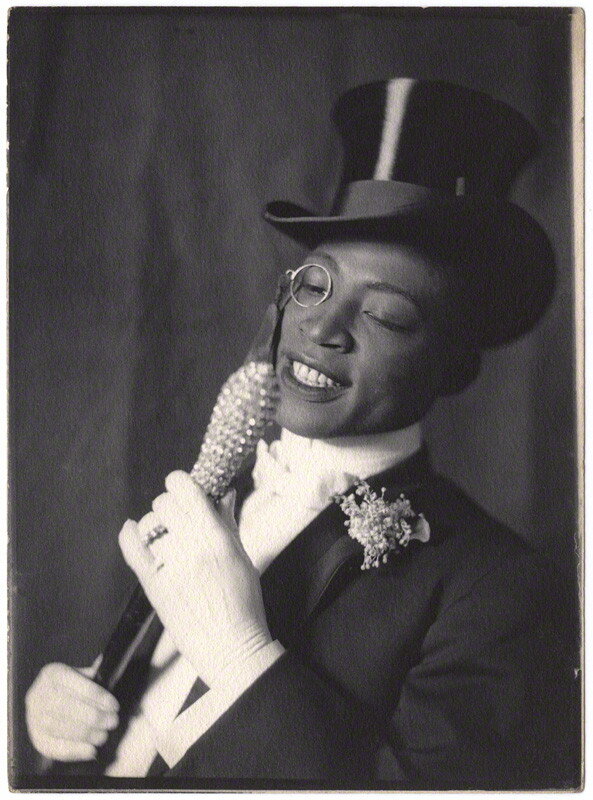

1. The cast of In Dahomey at the New York Theatre, 1903. (New York Public Library) 2. Boston Globe, 1902. The early productions of In Dahomey featured Madah Hyers (of Hyers Sisters fame) as “Aunt Beck.” This is the last performance we have found for Hyers, who left the show mere weeks before it arrived on Broadway. 3. *Indianapolis Freedom* theater critic Sylvester Russell tracked the show's progress. 4. *Indianapolis Freedom,* 1902. Russell's review of the show's Stamford, CT launch found much room for improvement. 5. Sheet music, "Evah Darkey is a King," 1902. Performed by Bert Williams. 6. Sheet music, "I'd Like to Be a Real Lady," 1902. Performed by Aida Overton Walker. 7. *Indianapolis Freeman*, 1902. A few weeks after his first review, Russell was much more impressed. 8. George Walker and Bert Williams as Rareback Pinkerton and Shylock Homestead, 1903 (New York Public Library) 9. Hattie McIntosh, Walker, Aida Overton Walker, Williams, and Lottie Williams. (New York Public Library) 10. *Indianapolis Freeman*, 1903. Russell's review of the Broadway production. 11. Sheet music, "I'm a Jonah Man," 1903. This song became a signature song for Bert Williams. 12. Advertisement for *In Dahomey* at the Shaftesbury Theatre in London, 1903. 13. George Walker, 1903. Photo by Cavendish Morton (National Portrait Gallery, UK). 14. *Indianapolis Freeman*, 1904. Russell's review of the show after its seven-month stint in London.