EPISODE 4

Aida Overton Walker

1912

Episode 4: The End of the Beginning (1910-1922 + now)

What falls apart, what shifts, and what remains? A conversation about the legacy of the minstrelsy era.

Hosted by: Brittany Bradford

Guests include: Michael Dinwiddie, Rhiannon Giddens, Ayanna Thompson

Featuring the voices of: Galen Kane, Korey Jackson, Motell Foster, Steven Anthony Jones, Toussaint JeanLouis

Produced by: CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience

Conceived and Written by: CLASSIX (Brittany Bradford, A.J. Muhammad, Dominique Rider, Arminda Thomas, Awoye Timpo)

Sound Design and Editing: Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube

Associate Sound Engineer: German Martinez

Theme Song: Alphonso Horne

Original Music: Jeffery Miller

+TRANSCRIPT

BRITTANY Hello again friends! Welcome back to the CLASSIX podcast, (re)clamation, an intervention in the current conversation around theatre history, where we recenter and uplift the Black writers and storytellers of the American theatre - both the celebrated and the forgotten. I am your host, Brittany Bradford and this is episode 4 of our series on Black performance in the era of Minstrelsy. Last episode we looked at the early rise of Black musical theatre through the lens of Williams and Walker, and Cole and Johnson. This week, we’re closing out our analysis of the period and taking stock of what we’ve learned thus far. We’ll be examining what shifts in the form, what remains, and what falls apart.

VOICE OF LESTER WALTON “My, such a crowd! Oh, such a bill! And such a night…”

BRITTANY Unlike today’s reporters, New York Age editor Lester A. Walton did not seem to concern himself with “conflicts of interests” in his reporting. Certainly, in the summer of 1913, Theatre Critic Walton had no compunction about heaping praises on Frog Vice-President Walton’s latest endeavor:”

VOICE OF LESTER WALTON “The entertainment will go down in history as the biggest and best of its kind ever participated in by members of the colored theatrical profession...Every available seat was taken in the casino and hundreds became candidates for a Carnegie medal by heroically standing in new shoes for over two hours...And the show! It cannot be recalled when so many stars of the colored theatrical firmament twinkled and glittered at one time on any stage.”

BRITTANY To be fair, Walton had reason to celebrate. In the five years since its founding, the Frogs had expanded their membership and their reach. Its annual gala, the Frog Frolics, drew visitors from out-of-state; and the annual shows they created had become successful enough to take on the road to Philadelphia or Washington, D.C. And earlier that summer, the Frogs had moved into their permanent headquarters, or Clubhouse - a 10-room red brick house on 132nd Street.

But besides the club, the Black arts community had suffered great losses. The Black Broadway shows like In Dahomey and Red Moon were already a thing of the past, at least for now. Good reviews and even audiences around the country had been no match for the white theatre circuits and bookers who made it impossible to get the houses and bookings to make producing sustainable.

Compounding their miseries, the Frogs had lost two of its charter members and brightest visionaries. George Walker took ill in 1909, suffering stuttering and memory loss while touring in Bandanna Land. The next year, Bob Cole collapsed on stage in the middle of a performance with J. Rosamond Johnson. While the newspaper accounts claimed emotional breakdowns or mental health problems, both men likely suffered from end-stage syphilis. George Walker and Bob Cole died in 1911. The loss of these men -- as artists, as members of the two most successful Black partnerships, and especially as fierce advocates for Black performers and Black performance -- was profound, and even in this triumphant 1913 evening we can see those left behind struggling to find the way forward.

The format for the evening’s presentations, strangely enough, was a three-part minstrel show. And for the first section, all the performers were in blackface. The Frogs had gotten the idea the year before, where at the previous year’s show - even performers like J. Rosamond Johnson, who had never blacked up before, put on the black cork for the first part of the night. The experiment had been such a success that they decided to repeat it this year as well. For the First Part of the minstrel act, celebrating the Colored Profession’s past, Frog President Jesse A. Shipp (of In Dahomey fame) took the role of interlocutor, and one of the highlights included “the Dean,” Sam Lucas. Now “seventy years young, ” Lucas, who, due to health problems, had announced his retirement the week before, gave a rousing rendition of the song “I Was All Right in My Younger Days”. Of course, with Sam, retirement was a relative thing. In addition to occasional appearances with the Frogs, he would go on to work in two films: One, Bert Williams’ The Lime Kiln Club, which wouldn’t see the light of day for a century; and the first filmed version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1914, with Sam once again in the title role. The part that made him famous was the last that he would play.

Beloved as he was, however, Sam Lucas was not the reason behind the crowd’s overflow. That honor belonged to the man who closed the first act:

VOICE OF LESTER WALTON "Of course, Bert A. Williams was the principal attraction. He had not been seen by many colored playgoers for three or four seasons."

BRITTANY After his partner’s sudden illness,Williams had briefly attempted to keep the company going on his own. The 1909-1910 production, Mr. Lode of Koal, starring Williams with a book by Shipp and music by Alex Rogers and J. Rosamond Johnson, would be the last Black show on Broadway for another decade. After it closed, Williams had taken a position with Ziegfield’s Follies, a career move that had served to make him the most famous Black man in America, though still not especially well-protected. Williams was the only member of the Follies not invited to join the newly formed Actors Equity Association. The move to the Follies had also taken him away from the Black theatre community, creators and audiences he had helped to build. But on this night, at least, he was back, partnered with vaudevillian and theatre entrepreneur S.H. Dudley. Tonight was Mr. Williams’ hom\ecoming, and he used it to do something a little different.

VOICE OF LESTER WALTON “Mr. Williams was seen for the first time in his career in the role of a dusky damsel, who was all dressed up in a slit skirt and other female toggery. Mr Dudley appeared as Mr. Williams’ gentleman friend. They sang an old song, “Goo Goo Eyes,” and then proceeded to tickle the funny bone of all present in a grotesque dance which would have made even old man Groucho himself laugh.”

BRITTANY Next came the Olio, celebrating the talents of present stars, and if Williams’ appearance was the highlight of the first part, the Olio belonged largely to his former castmate, Aida Overton Walker. Though Frog membership was not extended to women, as the founder’s widow, Overton Walker had a special connection to the group. After her husband’s illness, Overton took over his role in Bandanna Land. In the time since Walker’s death, she had gone on to become, per the Pittsburgh Courier, “the foremost woman of color on the stage today”. She had branched out into producing acts - the Porto Rico Girls and the Happy Girls - and experimented with creating her own troupe. This night was the first time in several years that Williams and Overton Walker would appear on the same stage, and there was speculation that they might perform together, for old times’ sake. Alas, it was not meant to be. Instead, Overton Walker performed two songs before closing out in a dance, “The International Rag,” with Shipp. She and Williams did share one thing in common though that night:

VOICE OF LESTER WALTON “What did Miss Walker wear? Why, a slit skirt; and, believe me, the slit could not ride on the street cars for half fare, either. Some full-grown slit!”

BRITTANY In a hopeful nod to Black Performance’s Future, the finale featured a sketch by the Negro Players, a young stock company based at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, founded by Alex Rogers (formerly in Williams and Walker shows) and Henry S. Creamer (formerly of Ernest Hogan’s company). Facing the sudden death of Black plays on Broadway, Rogers and Creamer were determined to rebuild, as Bob Cole had once attempted in his time at Worth’s Museum, by developing young talent while producing “playlets of real Negro life.” Unfortunately, the hits will keep coming for this group. In a little over a year, Black theatre will say an abrupt farewell to Aida Overton Walker, who succumbs to kidney disease at 34. Seven years later, onstage in a production of Under the Bamboo Tree, Bert Williams will suffer a stroke and die soon after, at 47. We can only dream of the progress that might have been made if so much of this visionary generation had not been cut off at their prime.

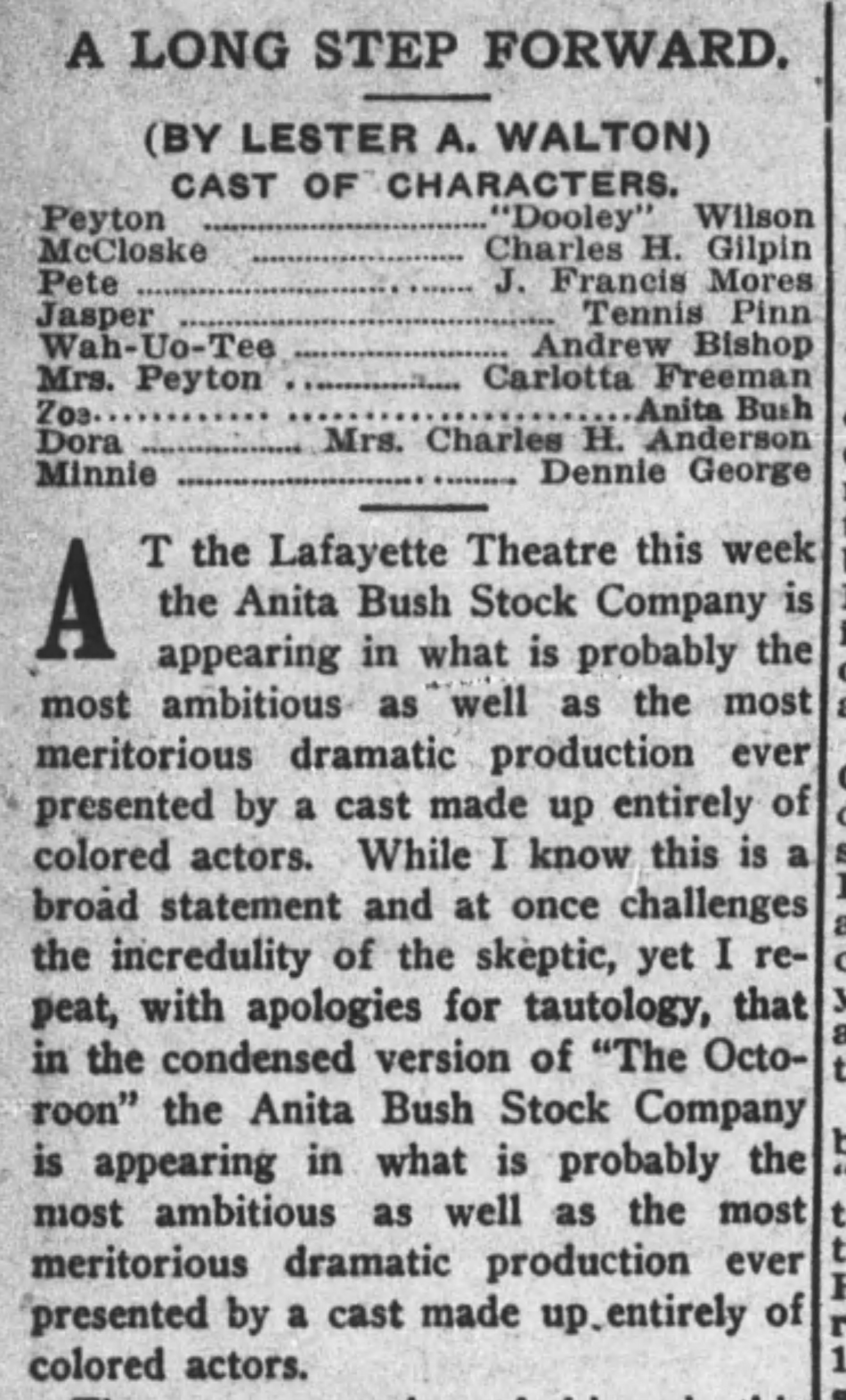

Rogers’ and Creamer’s foray into building a stock company met the same fate as Bob Cole’s had twenty years earlier but others would continue to carry the torch forward. New visionaries like Anita Bush, a chorus girl in the Williams and Walker Company, would go on to found Harlem’s first permanent dramatic stock company, the Lafayette Players, which would become a catalyst for the Harlem Renaissance.

But that is another story.

Thank you so much for joining us this week as we look at the end of the minstrelsy era. My name is Brittany Bradford and you’re listening to Episode 4 of (re)clamation.

At the beginning of our research one of the words that kept coming up for us in thinking about the minstrelsy era was choice. We’ve all seen the posters, the figurines. Why were these artists choosing to put on blackface? As we’ve followed so many artists and troupes along the way we’ve had to wrestle with a central question - If you were a musician or had dreams of being an artist in this time, where would you turn, what would you do?

The general disdain that capital-A America had for Black people created a terror-filled environment both on the road and in the cities and towns across the country where these artists lived. The work in minstrel shows and beyond changed the lives of Black performers and that performance legacy reverberates immensely to this day. In his book, “100 Years of the Negro in Show Business”, Tom Fletcher gave a first-hand account of what it was like to work during this time -

VOICE OF TOM FLETCHER “It was a big break when show business started, because singing and dancing was the way in which they had amused themselves for years. The managers of different shows would send their scouts looking for talent. Salaries were not large, but they still amounted to much more than they were getting, and there was the added advantage of the opportunity to travel with the company taking care of them. And so these recruits went forward, with nothing to fight with but their talent. With bands playing and banners flying they marched into and all over towns on three different continents. They even went into the deep south, into towns which had prominent signs reading: “Nigger, Read and Run.”

All of us who were recruited to enter show business went into it with our eyes wide open. The objectives were, first, to make money to help educate our younger ones, and second, to try to break down the ill feeling that existed toward the colored people.”

AYANNA THOMPSON “I mean, I love that, I love the premise that you guys are celebrating the Black actors who tried to find a way in this kind of horrific performance tradition. But I have to say, for me that that wasn't a narrative of uplift.”

BRITTANY That last bit was from renowned Shakespeare scholar and Renaissance professor Ayanna Thompson. She has just written a wonderful book called Blackface that you hopefully can all check out. It lays out the presence of contemporary blackface and traces it back to its roots. We talked about blackface performance.

BRITTANY INTERVIEWING AYANNA THOMPSON And putting on just like our 21st century scholarly cap on it, do you think that it matters whether or not black performers were or weren't in blackface when we're analyzing and talking about it now?

AYANNA THOMPSON Ah, yes and no. Right. So I think it matters because it's a damaging performance mode. It is one that signals that it is owned by--it’s white property. Right? performing blackness in a racial prosthetic is white property. And I think for black performers to attempt to appropriate that, I think, can fail. And we know this from 21st century experiences like Dave Chappelle’s Black Pixie skit was the thing that sent him to Africa and off of his multi-million dollar deal, right? Like he realized he could not fully own and appropriate that blackface minstrelsy tradition, even when he was doing it from the seat of power. So I think it, you know, whether or not they use the makeup ends up being, you know, probably the hardest part of it. But if you fall into recreating the genre, even without the prosthetic, I think that that's problematic as well.

BRITTANY To say that the legacy of minstrelsy is complex would be a complete and total understatement. Both then and now, artists, journalists and thinkers were and are contending with the art and performance of the era and thinking about its resonance with the national audience.

Their observations come from a variety of lenses and perspectives. In the eye of the performer there’s opportunity for artistic and professional development; from the eye of the audience of the time, there’s either a new dawn of Black entertainment or there’s a true and appropriate disdain about the growing and persistent stereotypical image of Black people on the stage; from the eye of the critic there’s a sense of competition and intrigue as they follow the dizzying array of performers and performances in a post-Civil War world. And through it all there’s a persistent attempt in the country at large to dehumanize Black people at every stage of our existence.

How on earth do we begin to contend with the legacy of this time?

Let’s take a look at how artists and scholars have tried to make sense of it all -

In an era where some pastors even threatened to kick people out of the church if they went to see a minstrel show, Father of the Blues, W.C. Handy, noted that many what he called “upper crust Negro friends and family members” questioned his decision to be in minstrel shows.

VOICE OF W.C. HANDY “It goes without saying that minstrels were a disreputable lot in the eyes of a large section of upper-crust Negroes...but it was also true that all the best talent of that generation came down the same drain. The composers, the singers, the musicians, the speakers, the stage performers-- the minstrel shows got them all.”

BRITTANY Sam Lucas had tales of his own uncomfortable run-ins with disapproving clergy. Still, in his 1915 eulogy for Billy Kersands, and less than a year before his own death, Sam Lucas offered this defense and observation of his profession -

SAM LUCAS “The minstrel was the first door of entrance opened to Negroes on the American stage, just as now men and women of the race possessing unusual talent for serious roles of legitimate drama are compelled to confine themselves to comedy. But it will not be many years before the new public will applaud the rise of the curtain upon Negro actors and musicians who will shine as stars of the first magnitude, both as composers and performers of the highest forms of amusement and entertainment that have ever given interest to the stage.”

BRITTANY You know the expression, “the road to hell is paved with good intentions?” If the story of minstrelsy isn’t a warning for the future and also a lesson for us all, who knows what is?

Throughout the minstrelsy era, performers created and perpetuated tropes about blackness, tropes that have threatened lives, damaged relationships and created nearly unshakeable stereotypes.

And also, these artists and producers created some of the most transformative music and theater pieces of their time and created new opportunities for Black people. They planted seeds and made incendiary and visionary calls for the future of Black performance that we echo now.

James Weldon Johnson had some thoughts on these contradictions -

JAMES WELDON JOHNSON “Minstrelsy was, on the whole, a caricature of Negro life, and it fixed a stage tradition which has not yet been entirely broken. It fixed the tradition of the Negro as only an irresponsible, happy-go-lucky, wide-grinning, loud-laughing, shuffling, banjo-playing, singing, dancing sort of being. Nevertheless, these companies did provide stage training and theatrical experience for a large number of coloured men. They provided an essential training and theatrical experience which, at the time, could not have been acquired from any other source. Many of these men, as the vogue of minstrelsy waned, passed on into the second phase, or middle period, of the Negro on the theatrical stage in America; and it was mainly upon the training they had gained that this second phase rested.”

BRITTANY As Arminda would say, this time period has descendents. People who were working in this time created and inspired new generations of artists and those artists taught and inspired new artists too. We asked Michael Dinwiddie how he as a professor even goes about teaching this era to new generations?

VOICE OF MICHAEL DINWIDDIE That is a great question. And I'm, I don't even have to answer it. Because I feel like my students already know about minstrelsy. They seen it performed all their lives. They've seen it performed in blackface, in white face, they've seen Vanilla Ice. They've seen Kanye West, they've seen it. Yeah, are we gonna broadcast this, but anyway, I mean, they've seen the ways in which we perform for people other than each other. And then you also see the ways in which our culture has been appropriately, expropriated and basically manipulated for other people's advantage. So for instance, years ago, there was a show in New York called The Scottsboro Boys, brilliant performances, wonderful on stage, but a show in which the writers, the producers, the directors, no people of color at all. So that influenced the ways in which the show came to be perceived. Now, I should tell that I was very offended, because in the show, there's a dance that a young Black guy is doing, and he's basically being electrocuted. So, you know, that's, that's like a tap dance. Right? That's what I recall. But when I spoke to a lady named Billie Allen Henderson, Billie Allen was married to Luther Henderson. And she herself had been a performer. She died a few years ago, but she remembered the Scottsboro Boys case, as a child, she said, I'm glad the show was done. I'm glad that it was done. And it's so that people could know about it. But my reaction to it was, well, it was like a minstrel show because you have black performers, but it's all a different vision of how to utilize and put black people on stage. So the way I introduce it to my students is like, look around, where do you see it? You know, where do you see minstrelsy?

BRITTANY Here’s Rhiannon on her personal reckoning with minstrelsy through the music.

RHIANNON GIDDENS The way I was raised and the way that the narrative often goes is, you know, Black music’s over here, white music’s over here, you know, and it doesn't work that way. That's not the way it was. So, for me, it's like, once I started learning that and, and learning more about that I realized that minstrelsy itself is some of the earliest, just record of music that Black people helped create. And so for me, that was the first step in not just sort of slapping it off the table and going well, all this horrendous, you know, sort of offensive stuff that goes along with that. And then when you learn more about, obviously, you know, we do what we do, which is we, within the structure that we're sort of forced into, we create all of these new ways of subverting, and all this kind of stuff. So, it's like, not only are we, the co-creators of the music that goes into minstrelsy, we're also, you know, how we took those tropes and how--what did we do with them, all of that is, is, you know, I think, pieces of our, of our culture and history, not only as Americans, but as African Americans that need to be reclaimed.

So much of minstrelsy is based on observational sort of appropriation. You see, you take and then you try to create something from that, and then that becomes the thing, and then it's your thing that was taken and modified, and, you know, appropriated, and you have to work within that system. So you then take that thing and then create something even - You know, and it's like, it for me, it begins that pattern of, of creation, appropriation, reclamation, creation, appropriation, reclamation, that that, you know, is at the basis of so much of American culture. Minstrelsy for me is like one of the very first moments where that's happening.

BRITTANY And here’s Ayanna Thompson’s take -

AYANNA THOMPSON I think one of the lessons is that the popular performance mode right when minstrelsy was coming together, was this slice of life--not, not, you know, obviously, it's before cinema, so it's not cinéma vérité, but it was like a comic, like, here's a trip to the country. And here's, here's, you know, people that you've never seen before. And that if you get in that performance mode, it often means creating stereotypes where the audience gets to laugh at the foreign other, whether it's, you know, plantation life, or the Scottish Highlands for the, some English comedians at the time, or whatever. But - so I think that that's one thing to think about, like, who, who's, who gets to create the genre, who gets to create the stories that are told in that genre, and then who's the intended audience for it? And, you know, one thing to circle back to the Tyler Perry/Spike Lee debate is that I think the--Tyler Perry's working assumption is that Black people have full command over what they think is funny. And actually, that it's part of a larger cultural dialogue. That's not, that's not ever a pure thing. We're in a racist society. So yeah, you're taught to laugh at racist jokes. So I think that's, that's, that's part of my takeaway.

BRITTANY INTERVIEWING AYANNA THOMPSON There are some scholars who do argue that things like the introduction of spirituals into minstrel shows might have been subversive, that certain individuals working within the form might have used it as a mode for subversion or conscious critique. What do you think about that? Is there a way to do that within it?

AYANNA THOMPSON Of course, yes. And I think there are ways for individual performers and individual audiences to get to that subversive space. Certainly, if you are performing something that allows for a different emotive trajectory, one that allows for a view of humanity between people, that that's a subversive act. Now, does that undermine the structure, the systemic racist part of minstrelsy? No. But there are ways for individuals to claim a power authority authorship in that moment that I think are powerful for the individuals. What I would like, of course, is for us all to think about that larger superstructure and how we dismantle that as opposed to just working within it.

BRITTANY So here we go. The takeaway of it all. In these last four episodes we have explored everything from what it was like to be a black manager of a troupe, to black opera singers traveling across the country, to black theatre collectives being formed and carving a path for a new generation. It’s hard to know how to sum everything up. And in truth, there isn’t really a summation to be had, I still have so much to learn about this era. So let’s not put the cart before the horse. Let’s just chat about some things.

There were parts of this history that I didn’t know before, that have really stuck with me, one of the largest being the whole idea of blacking up. And who was doing it. And their paradigm on it. And who was not. As we learned when examining the Georgia Minstrels in Episode 1, there were those who performed in blackface and those who didn’t. With or without the cork, early minstrel shows still had plantation skits, there were still stereotypes and caricatures being presented, but it does make one wonder: how does the material change when seeing it on a black body, and then seeing it again on a black body presenting as a different performative bastardized black body? What does the mask do? Not only for the audience, but the performer as well? And what was it for those in, say, the Georgia Minstrels, who may have begun their career NOT blacking up, to then finding it the new norm?

And what about the literal process of adding cork to one's own face? What was it, to sit in a chair night after night, whether in a tent in the woods in a small southern town performing for mostly black farmers and sharecroppers, or in a theatre in New York, for an audience composed of not only your own brothers and sisters, but the white people who created this form, this form that perhaps you are trying to take back ownership of, but yet are still putting on this burnt cork mask?

And this conversation is challenging, right?, because we’re looking at blackface on black people through a 21st century lens. For a time I wondered if the complexity that I felt about what it would be like to do that as an artist, is something that I put upon the narrative, wanting it to be a really difficult decision for these black artists, wanting in my heart for all of them to have secretly been trying to stick it to the man through moments of subversion in the shows. And while we know some people’s intentions because they wrote them down- like Bob Cole and James Weldon Johnson, lots of others are purely speculation. Many of the answers to these questions have gone to the grave with those involved. But it’s also slightly beside the point, I now realize. There were artists who didn’t think about, nor care, about the social implications of blacking up, there were others who did it for the art, and the blackface was a compromise they were willing to undertake to pursue their dreams, and yes, there were others who saw it for exactly what it was, and tried to subvert it. Tried to do something with it, to use it as a way to create an even larger social commentary. While I might look back and hope that I’d be the latter rather than the former, it doesn’t change the need for the exploration. All of these realities deserve to be examined, even if they are hard to reckon with now.

And something else to reckon with is the extent to which the art of minstrelsy was spread throughout the world, for better or for worse. Ayanna Thompson really helped put this into perspective when we spoke with her about it. Part of the takeaway is the distorted imagery of blackness that gets seen, but the other takeaway is how far back Black American artists have been trying to find a new reality for themselves in another country, either by choice or by force. In Europe alone, we see it with Paul Robeson, James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and Ralph Ellison. I don’t know that many of us, myself included, think of that same migration with regard to minstrel artists. It is eye-opening to realize black American artists were hoping to reinvent themselves as far back as the 1820’s with Ira Aldridge, and the 1870’s and beyond with black minstrel performers specifically. That optimistic opportunism, the legacy of travailing new lands, the conversation about identity and how to actualize that for oneself, has been in our DNA as Black artists for longer than I had previously imagined. That’s part of our history too.

And on the positive, I also fell in love during this process with so many of these people. I can’t stop thinking about Bob Cole and his brilliance. About Charles Hicks and his genius and entrepreneurship. I giggle at the slyness of Williams and Walker calling themselves the Two Real Coons, and feel like I’m in on a joke. I think about Ada Overton Walker and wonder how I can take ownership of my own Black female body. I imagine being a fly on the wall at the Marshall Hotel, and how miraculous and charged and passionate and wonderfully alcohol-filled that must have been even if I fall asleep after one hot-toddy. I dream up scenarios that may or may not have even occurred, imagining a Harlem Renaissance before the Harlem Renaissance, thinking about all of those artists in communion with each other at Worth’s Museum, or at a Frolic of the Frogs event, imagining the creative collaborations and disagreements with different types of artists at the height of their artistic output, that would have occurred. They have become living, breathing, beautifully complex and flawed people in my mind, and I am grateful that I have been given the chance to get to know at least parts of them.

In Episode 1, I posited, “Is it possible to not have to cancel an entire subset of black art, but perhaps to learn how to examine it?”

So, in the beginning, I hoped that this exploration would help to give me a better understanding of the legacy we come from, and the shoulders upon which we stand, and it absolutely has. And, what I feel at this very moment, through the countless conversations and interviews that have occurred in the last year or so, is that, no, of course not, we don’t have to throw it all away and pretend it didn’t exist. The work to do is in the question. It is to learn how to give it, and the Black artists within it, the in-depth critique, with all its ickiness attached, that the form absolutely deserves. It can withstand that. We can withstand that. As Rhiannon Giddens said when we spoke, it’s not about answering the question that is asked, but answering the question that should be asked. This was, I realize now, my journey (although I didn’t articulate it as such at the time). Finding the questions that should be asked of Black Minstrelsy. And even simpler than that: it’s about reframing and reclaiming the narrative so that those more thoughtful questions can come to the fore. It’s the very least that those artists are entitled to.

We started off this podcast reaching out to friends and other artists, to ask them what comes to mind when they think of black minstrelsy. After these past few weeks together, and all that we’ve learned, I’m curious to hear your musings as well. So what are you thinking about? What angers you? What excites you? What makes you confused? What is the thing you can’t stop playing over and over in your mind? Which artists are you excited to learn more about? Who do you wish we had talked about more? What kind of artist do you think you’d be if you were operating at that time?

Let us know, because this conversation isn’t ending, it’s really just beginning.

We may be done with the historical analysis but there are many ways to look at a movement. One of them is to examine the work that was made in the era. So next up: You’ve already met one of our CLASSIX team members, Arminda Thomas, when we spoke about the Hyers Sisters. And in Episode 5, you will meet the rest: Historian and producer extraordinaire, AJ Muhammad, CLASSIX creator Awoye Timpo and director, dramaturg and Saidiya Hartman lover Dominique Rider, will join us to take you through an exploration of the Williams and Walker play In Dahomey. That convo will also include excerpts of the piece. We’re doing a radio play y’all!

Until then: Thank you thank you thank you for going on this journey with me. Thank you to Professor Ayanna Thompson for adding her incredible voice to the esteemed group of individuals we’ve gotten to speak to on this topic. Again, Ayanna’s book entitled Blackface came out last year. It’s a must read, please go support her work. For more information on the legacy of Black Minstrelsy, please visit theclassix.org and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @itstheclassix. This episode was produced by CLASSIX and Theatre for a New Audience. Our sound engineers are Twi McCallum and Aubrey Dube. The theme song was composed by Alphonso Horne. The episode music was composed by Jeffery Miller. See you next week!

GUEST BIOS:

Ayana Thompson

Ayanna Thompson is a Regents Professor of English at Arizona State University, and the Director of the Arizona Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies (ACMRS). She is the author of Blackface (Bloomsbury, 2021), Shakespeare in the Theatre: Peter Sellars (Arden Bloomsbury, 2018), Teaching Shakespeare with Purpose: A Student-Centred Approach, co-authored with Laura Turchi (Arden Bloomsbury, 2016), Passing Strange: Shakespeare, Race, and Contemporary America (Oxford University Press, 2011), and Performing Race and Torture on the Early Modern Stage (Routledge, 2008). She wrote the new introduction for the revised Arden3 Othello (Arden, 2016), and is the editor of The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Race (Cambridge University Press, 2021), Weyward Macbeth: Intersections of Race and Performance (Palgrave, 2010), and Colorblind Shakespeare: New Perspectives on Race and Performance (Routledge, 2006). She is currently collaborating with Curtis Perry on the Arden4 edition of Titus Andronicus.

In 2021, Thompson was appointed to the board of trustees of the Royal Shakespeare Company, and in 2020 she became a Shakespeare Scholar in Residence at The Public Theater in New York. She chairs the Council of Scholars at Theatre for a New Audience in Brooklyn, NY, serves on the board of Play On Shakespeare, and previously served on the board for Woolly Mammoth Theater in Washington, DC.

She was the 2018-19 President of the Shakespeare Association of America and was one of Phi Beta Kappa’s Visiting Scholars for 2017-2018. From 2015-2017, Thompson served as a member of the Board of Directors for the Association of Marshall Scholars.

Michael Dinwiddie

Michael Dinwiddie is an award-winning playwright/composer and associate professor of dramatic writing at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study, New York University. He is editor of the upcoming Theatre Communications Group (TCG) publication On Holy Ground: An Anthology of Plays and Monologues from the National Black Theatre Festival. A dramatist whose works have been produced in New York, regional, and educational theater, Michael has served on the boards of New Federal Theatre, the Classical Theatre of Harlem, the Duke Ellington Center for the Arts, and the Black Theatre Network, among others. He is a contributing editor of Black Masks Magazine, and a member of the Dramatists Guild and the Television Academy. Select honors include a National Endowment for the Arts Playwriting Fellowship, the FAMU Theatre Medal, a Walt Disney Writers Fellowship at Touchstone Pictures, the NYU Distinguished Teaching Medal, and induction into the College of Fellows of the American Theatre.

Rhiannon Giddens

Rhiannon Giddens is a celebrated artist who excavates the past to reveal truths about our present. A MacArthur “Genius Grant” recipient, Giddens has been Grammy-nominated six times, and won once, for her work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a group she co-founded. She was most recently nominated for her collaboration with multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi, there is no Other (2019). Giddens’s forthcoming album, They’re Calling Me Home, also a collaboration with Turrisi, is due out this April and features songs of her heritage, sung to console her while she has been unable to go home to her native North Carolina due to the ongoing pandemic.

Giddens has performed for the Obamas at the White House and acted in two seasons of the hit television series “Nashville”. She has been profiled by CBS Sunday Morning, the New York Times, and NPR’s Fresh Air, among other outlets. She is featured in Ken Burns’s Country Music series, which aired on PBS in 2019, where she speaks about the African American origins of country music. She is also a member of the band Our Native Daughters with three other black female banjo players - and produced their album Songs of Our Native Daughters (2019), which tells stories of historic black womanhood and survival.

Giddens was recently named Artistic Director of Silkroad Ensemble, with whom she is developing a number of new programs, including The American Silkroad, an exploration of the music of the American transcontinental railroad and it’s builders. She has also written the music for an original ballet, Lucy Negro Redux (the first ballet written by women of color for a black prima ballerina), and the libretto and music for an original opera, Omar, based on the autobiography of the enslaved man Omar Ibn Said.

Giddens’s lifelong mission is to lift up people of color whose contributions to American musical history have previously been erased, and to work toward a more accurate understanding of the country’s musical origins. Pitchfork has said of her “few artists are so fearless and so ravenous in their exploration,” and Smithsonian Magazine calls her “an electrifying artist who brings alive the memories of forgotten predecessors, white and black.”

EPISODE 4 GALLERY

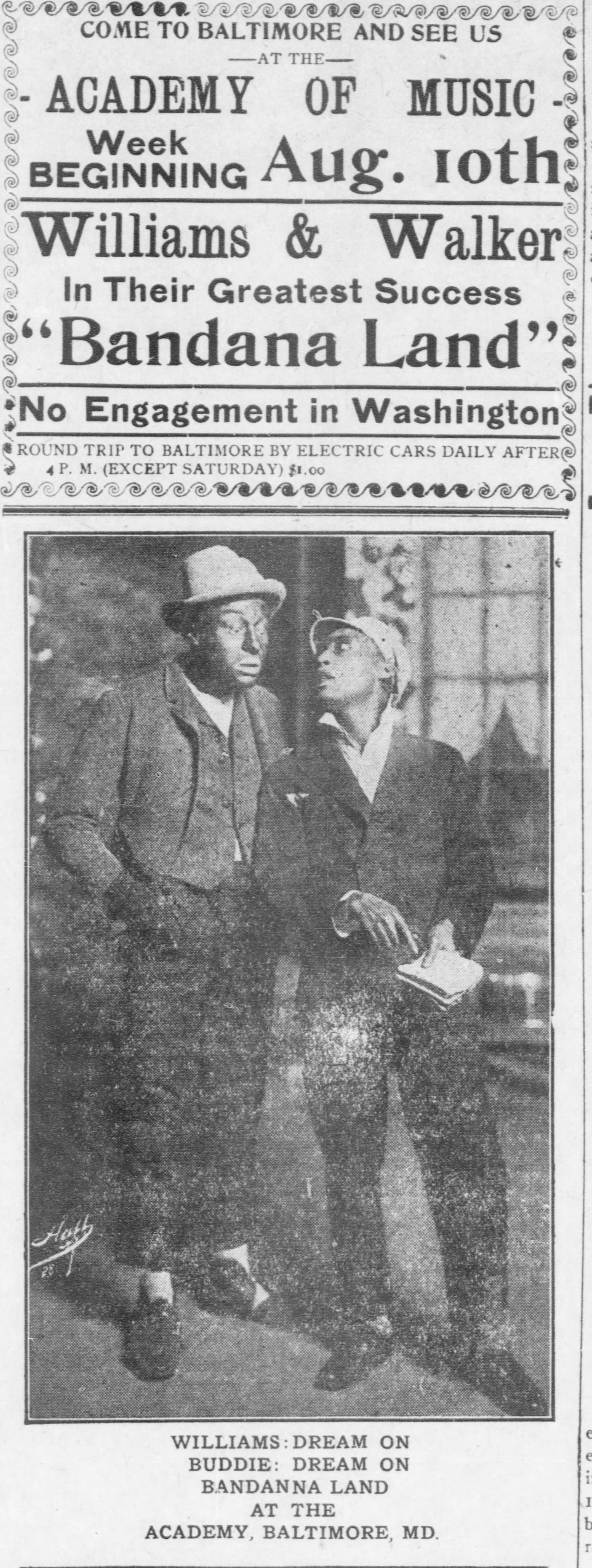

Washington Bee, 1908. An ad for Williams and Walker's Bandana Land, the last production the duo would appear in together.

New York Times,** 1911. News clipping on George Walker's death.

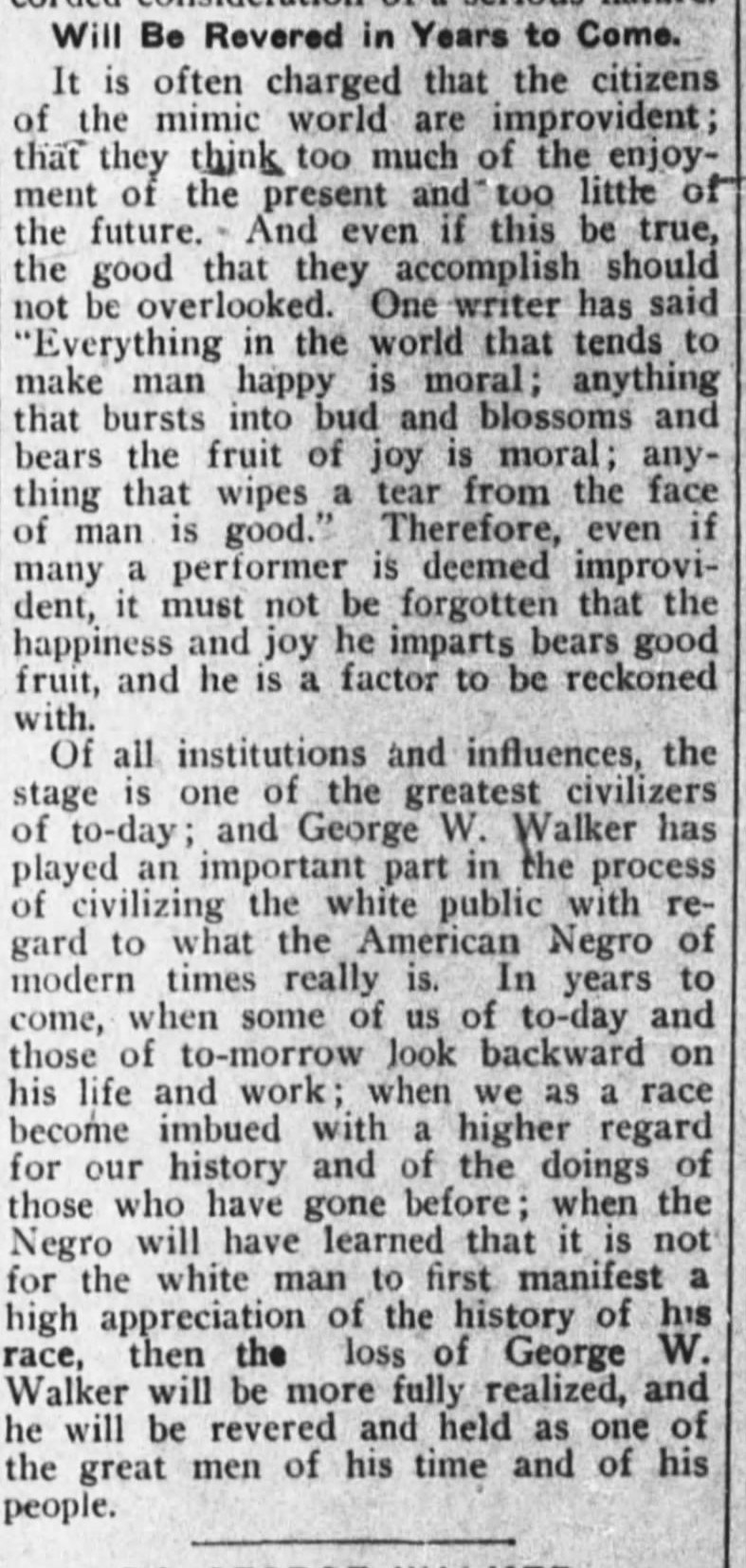

New York Age, 1911. An excerpt from Lester Walton's tribute to George Walker.

Sheet music, "That's Why They Call Me Shine," 1911. After the Williams and Walker Co. folded, Aida Overton Walker joined S.H. Dudley's Smart Set - sometimes performing in drag.

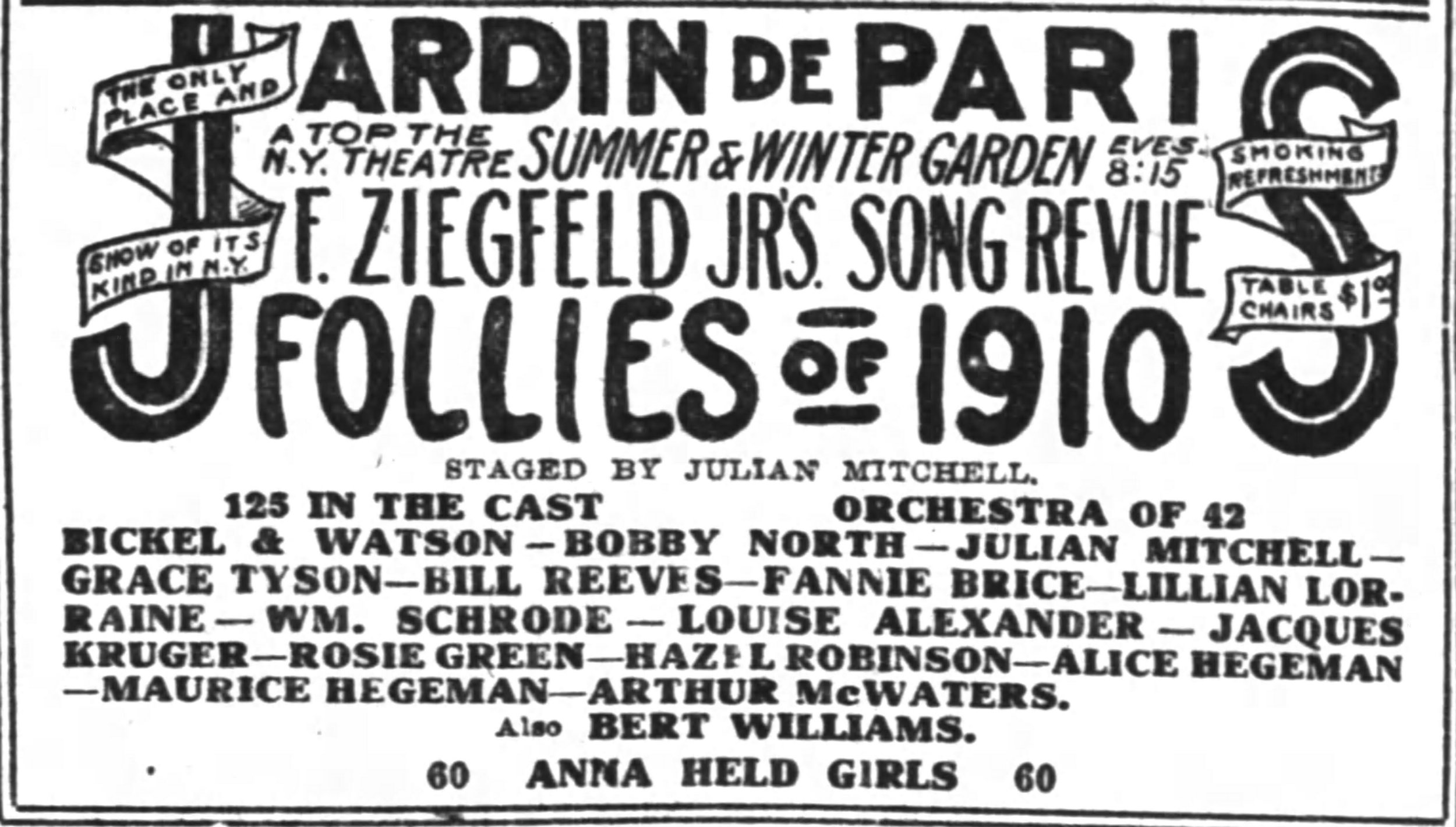

New York Times, 1910. Bert Williams became the first Black peformer in the famed Ziegfield Follies.

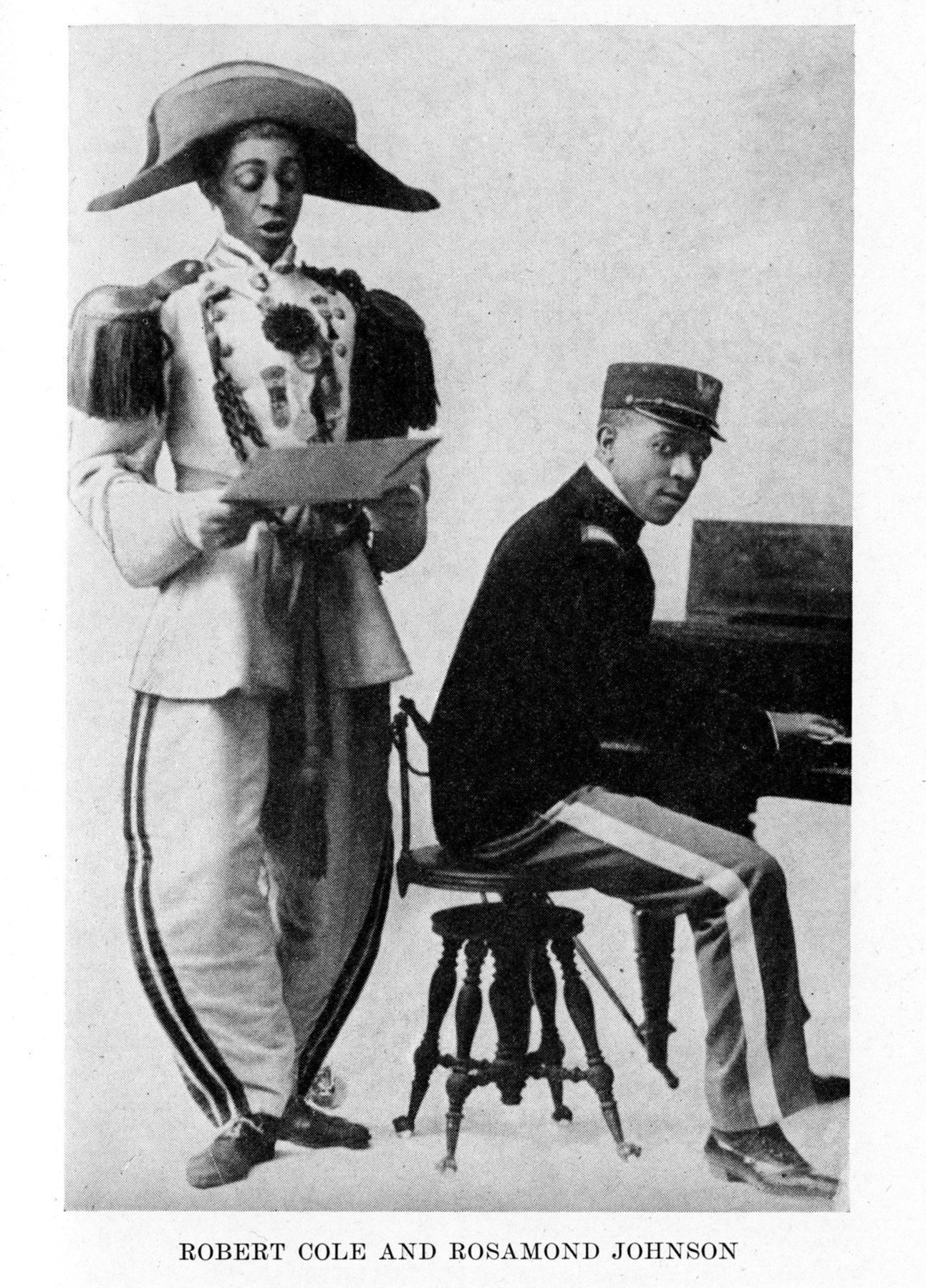

Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson (photo credit: Maud Cuney Hare)

New York Age, 1911. Excerpt from Lester Walton's tribute to Bob Cole

The Washington Bee, 1911.

New York Age Lester A. Walton - arts editor, columnist, composer, and producer.

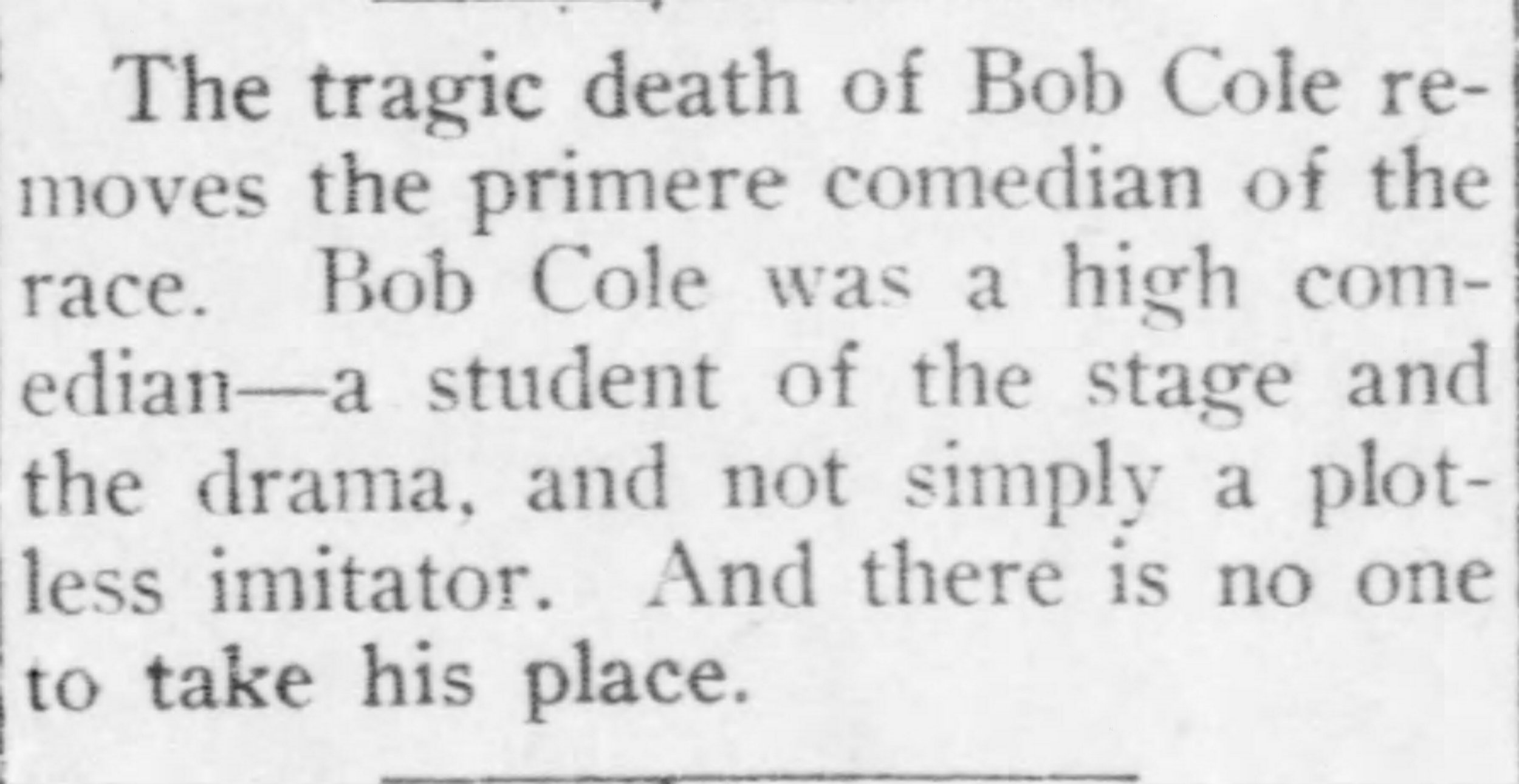

New York Age, 1912. Lester Walton's coverage of the Frog's Minstrel Show, featuring Sam Lucas.

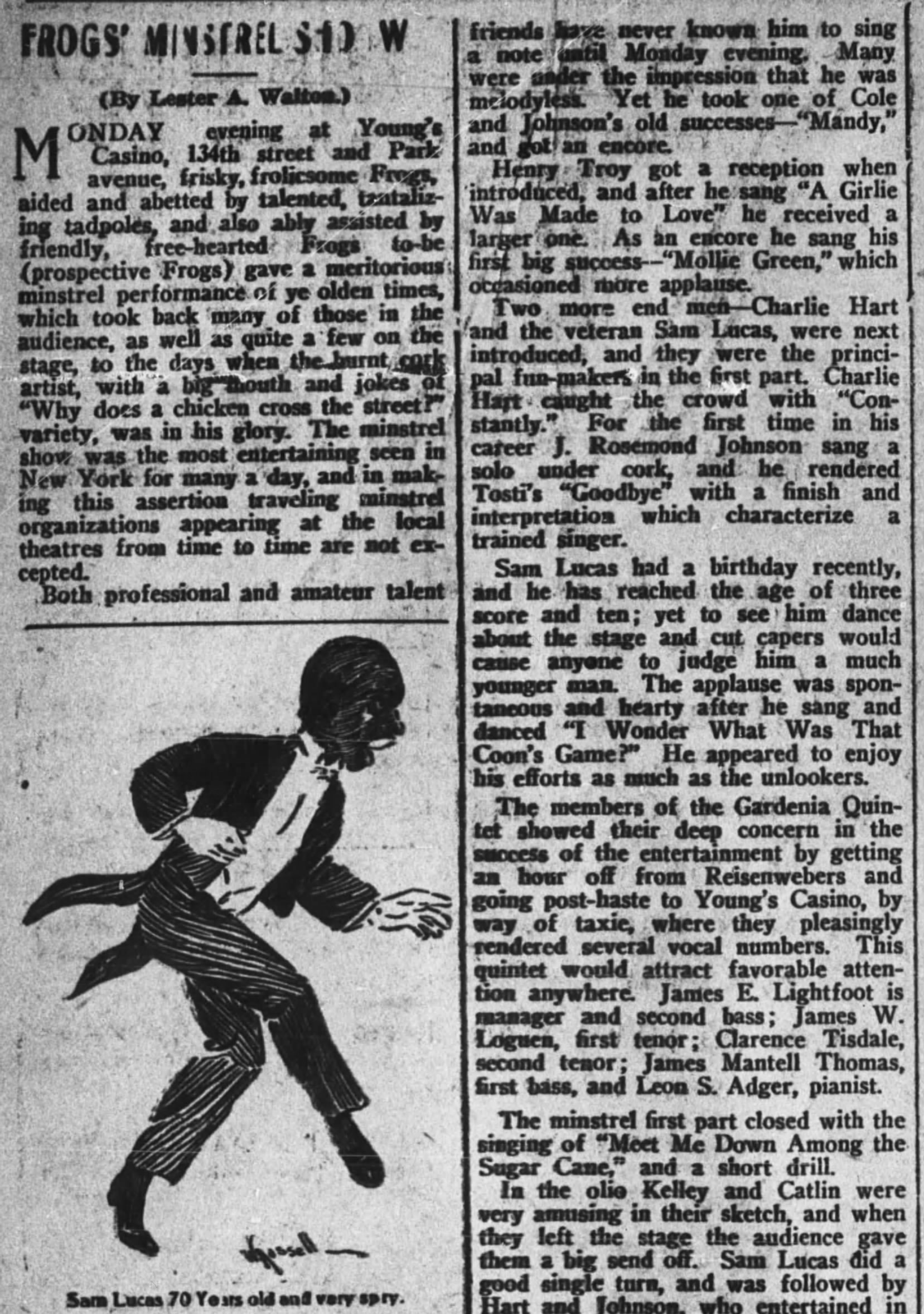

Aida Overton Walker, 1913

New York Age, 1914. Aida Overton Walker's sudden death at 34 was a shocking blow to the Black theater community.

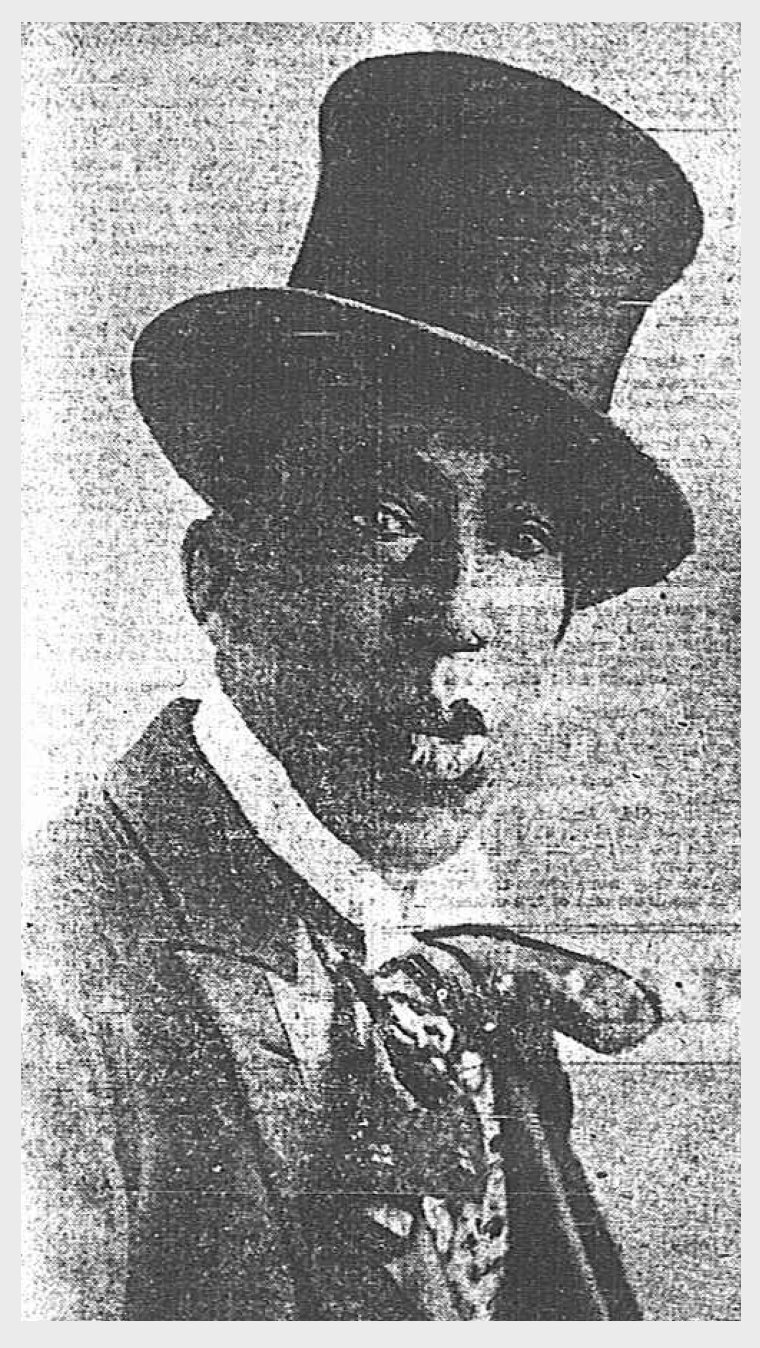

Sam Lucas, c. 1911. From the Georgia Minstrels to "dean of the colored theatrical profession.

New York Age, 1916. Excerpt from James Weldon Johnson's tribute to Sam Lucas.

New York Age, 1915. Anita Bush got her start as a chorus girl in the Williams and Walker Company.

New York Age, 1916. A review of the Anita Bush Stock Players, who would become the Lafayette Players, with some names that would be important in the next phase of Black theater history. But that's another story....

Bert Williams, c. 1921

The Pittsburgh Press, 1922. Announcing Williams' upcoming show, Under the Bamboo Tree - which would not make it to Pittsburgh.

New York Age, 1922. Excerpt from James Weldon Johnson's tribute to Bert Williams.

Sheet music, Cole and Johnson's "Under the Bamboo Tree". While the musical (with which Johnson was not involved) did not survive, this song itself had a much longer shelf life.